How do you take in the world around you? Do you detect what's going on through sensory input, or do you use perception to organize and interpret that information?

Sensation and perception explain how we recognize our friends when they approach us, how we form memories, and how we analyze what is going on at any given point in time.

What is Bottom Up Processing?

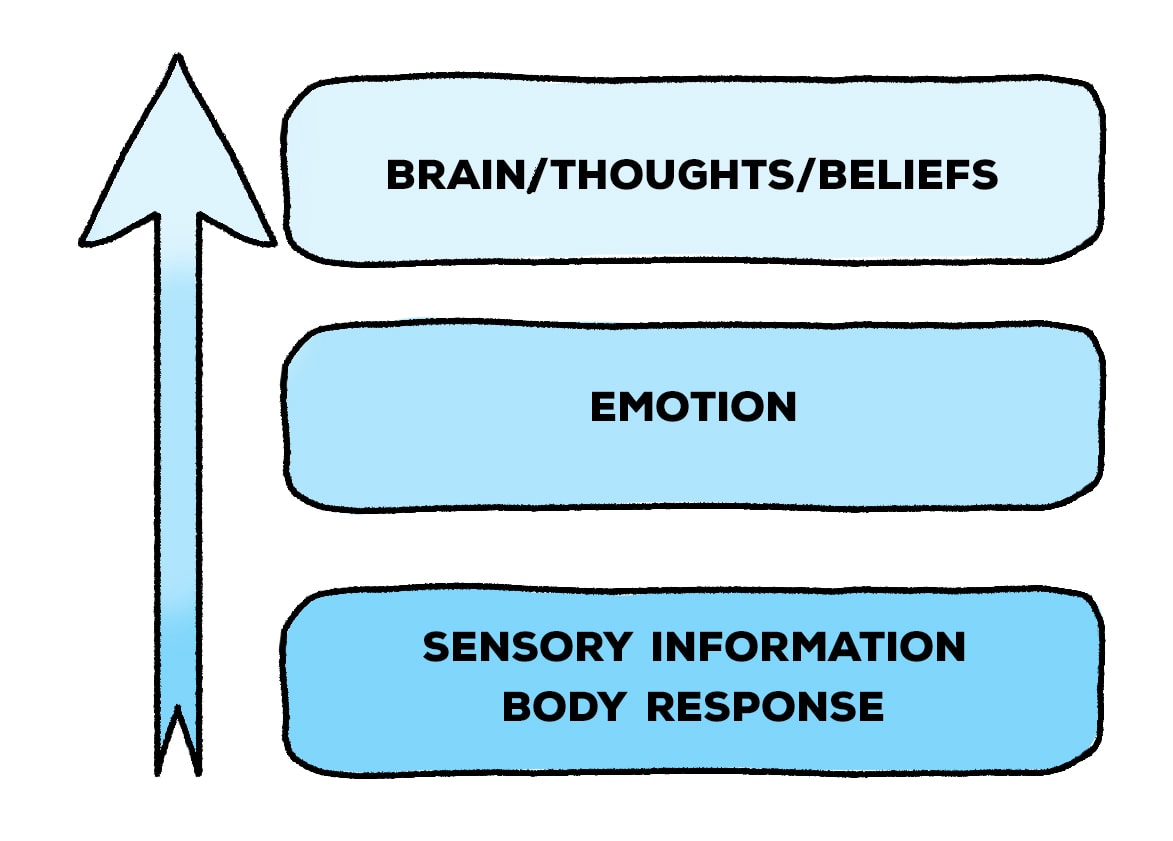

Bottom-up processing is the idea that we begin to perceive items with sensation, as opposed to our conceptual ideas. This process is also known as “data-driven processing” because it is just that: driven by the data that we collect with our senses.

Right now, you see a computer screen and some animations. But before you could recognize the computer, you took in the individual parts of the computer: the shape of the machine, the light emanating from the screen, each of the keys on the keyboard, etc.

Some psychologists argue that sensation and perception are two different processes. Some argue that they are the same.

We call these theories “bottom-up” and “top-down” processing. One argues that sensory and perception are the same and that we process stimuli first and analyze them later. The other is a “top-down process” that starts with memories, expectations, and motivations. We apply our knowledge and expectations to create a backdrop for our world as we perceive it and then focus on the smaller details using sensation.

I’m going to focus specifically on the bottom-up approach to processing and how we process the stimuli that are around us. James J. Gibson developed the theory of bottom-up processing, and his work has significantly impacted the world of psychology, behaviorism, and neurology.

Gibson’s Theory

The theory of bottom-up processing sounds easy enough, but Gibson’s theory on this process is still a ground for debate in psychology. Why? Gibson theorized that no learning is necessary to perceive stimuli. The process from looking at stimuli to analyzing them is a direct line. As the visual stimuli move from the retinas in the eyes to the visual cortex in the brain, we begin to move deeper and deeper into an analysis of what we see.

This is a reductionist theory. Reductionism is breaking down big ideas into their most basic parts. (This is the opposite of holism, which looks at the “big picture” ideas first.)

When you apply this idea to the nature vs. nurture debate, it is clear that Gibson takes the side of nature. He argues that we are solely using nature to perceive the world and analyze what we are seeing. He is one of the founders of ecological psychology.

Affordances

While Gibson was developing the theory of bottom-up processing, he coined the term “affordances.” Everything we see has several affordances or different opportunities to interact with the item.

An affordance is a thing that offers something to the perceiver more than what it specifically is. For the simplest example, a chair is a construction of wood. However, it 'affords' us the opportunity to sit in it.

These affordances include:

- Relative brightness or size

- Texture Gradient

- Height

- Highlighted objects

Gibson argued that the idea of affordances was crucial to bottom-up processing. He theorized that when we look at an item, we observe its affordances.

Examples of Bottom Up Processing

One simple example of bottom-up processing is walking to a friend's bathroom in the middle of the night. You have to turn the light on to see where you are going instead of using your memory of where things are in the bathroom.

Below are some more examples of bottom-up processing in everyday life:

1) Interpreting Road Signs

One of the ways that affordances work to support the theory of bottom-up processing is road markings. Road markings use several different affordances to communicate speed requirements and the direction of the world. As you’re driving along a country road, you are not working from the top down - you are sensing the signs on the side of the road and the road to determine where you are going and how fast you are going.

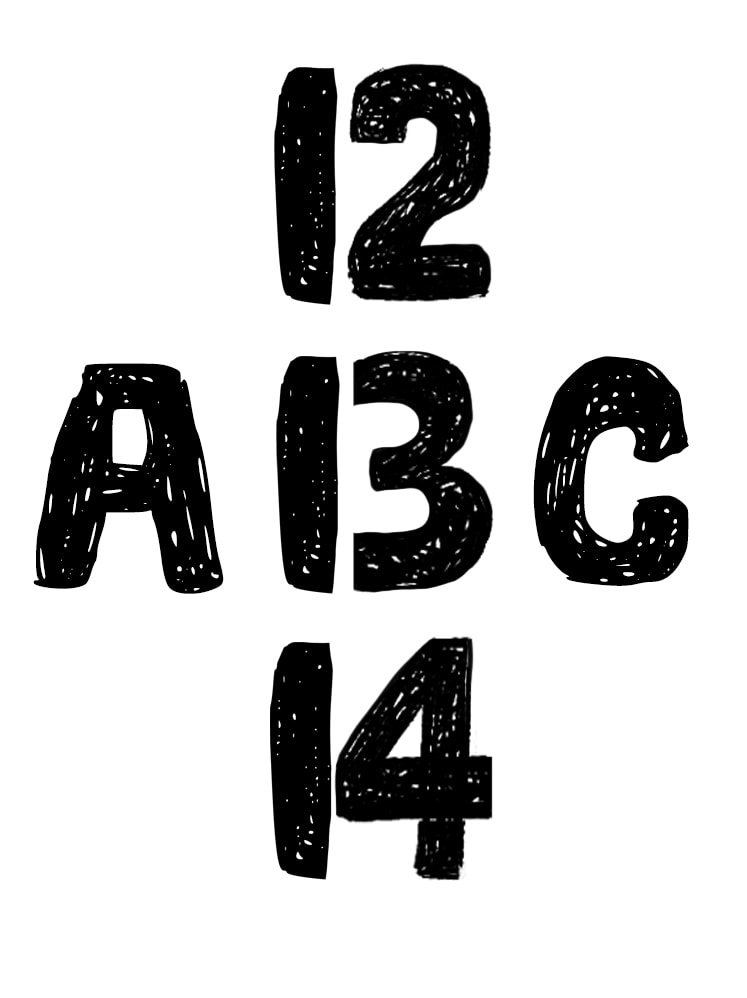

2) B or 13?

This next example is a two-part example that shows the difference between bottom-up and top-down processing.

Using bottom-up processing, you might look at the middle symbol and say it’s a “B.” Sure, you have learned what a “B” is in the past. But you did not need any context to look at the markings, send that stimuli to your visual context, and analyze the stimuli to determine that the markings were the letter “B.”

Top-down processing may yield a different result. Those two markings were placed between a “14” and a “12.”When you come across the two markings, you recognize it as “13.”You expect the markings to be numbers based on knowing what else is on the page. After some time, you might change your mind. However, your initial perception of the markings differed from the letter “B” due to top-down processing.

3) Prosopagnosia

Bottom-up processing can feel like a hard concept to grasp, especially if you think that your past experiences and the things you have learned are crucial to understanding the world around you. This is why so many psychologists align their thinking with top-down processing. But by looking at a condition in which the ability to use top-down processing is missing, you can better understand bottom-up processing.

So let’s look at Prosopagnosia.

Oliver Sacks is a well-known neurologist. His list of books includes The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat. (If you’re interested in anomalies in the world of neurology, I highly recommend this book!) Sacks himself could distinguish his wife from a hat, but he had trouble distinguishing other people’s faces, even the ones he knew. He had Prosopagnosia, which is also known as face blindness.

Patients with Prosopagnosia don’t use top-down processing to identify individuals. They are able to take in what they see when they look at a person’s face. They can identify whether the person has freckles, blue eyes, or a crooked nose. But they can’t identify whether or not they have seen that face before or who it belongs to.

The process in which people with face blindness take in the faces of others is an example of bottom-up processing.

4) Bottom-Up Tests and Assessments

How do you know how someone is feeling? They could tell you. Or, you could get clues from how the person acts and put together your final judgment. Many professional therapists use the second approach in tests and assessments. These are called “bottom-up assessments” because they resemble the bottom-up process.

Bottom-up testing and approaches vary depending on the type of therapy being practiced. For example, a cognitive behavioral therapist might ask their patient about a memory or a subject. They listen to what the patient has to say but also observe what is going on in the patient physically (sweating, fidgeting, etc.)They use this input to make their assessment.

5) Blind Taste Test

Have you ever seen someone do a blind taste test? Maybe they were a judge in a cook-off, or they were on a game show and had to guess what they were eating. They can probably guess they are eating food or have other clues about what they will put in their mouth. However, they must use bottom-up processing to assess what they are eating.

The taste buds help the brain with this - they send sensory information to the brain with little or no context. From there, the brain has to work to figure out what the person just ate.

6) Sensing a Fire Far Away

But you don’t have to be “blind” or shut your eyes to use bottom-up processing. Let’s say you’re in the woods. You see all the trees around you, but nothing else looks unusual. All of a sudden, you hear some popping noises. You smell the faint smell of smoke. After a while, you start to feel that one side of your body is exposed to heat.

All this tells you a fire is nearby, and it might be time to run or see if everything is okay. Your eyes can’t see the fire yet, but bottom-up processing with the help of your other senses tells you what is going on.

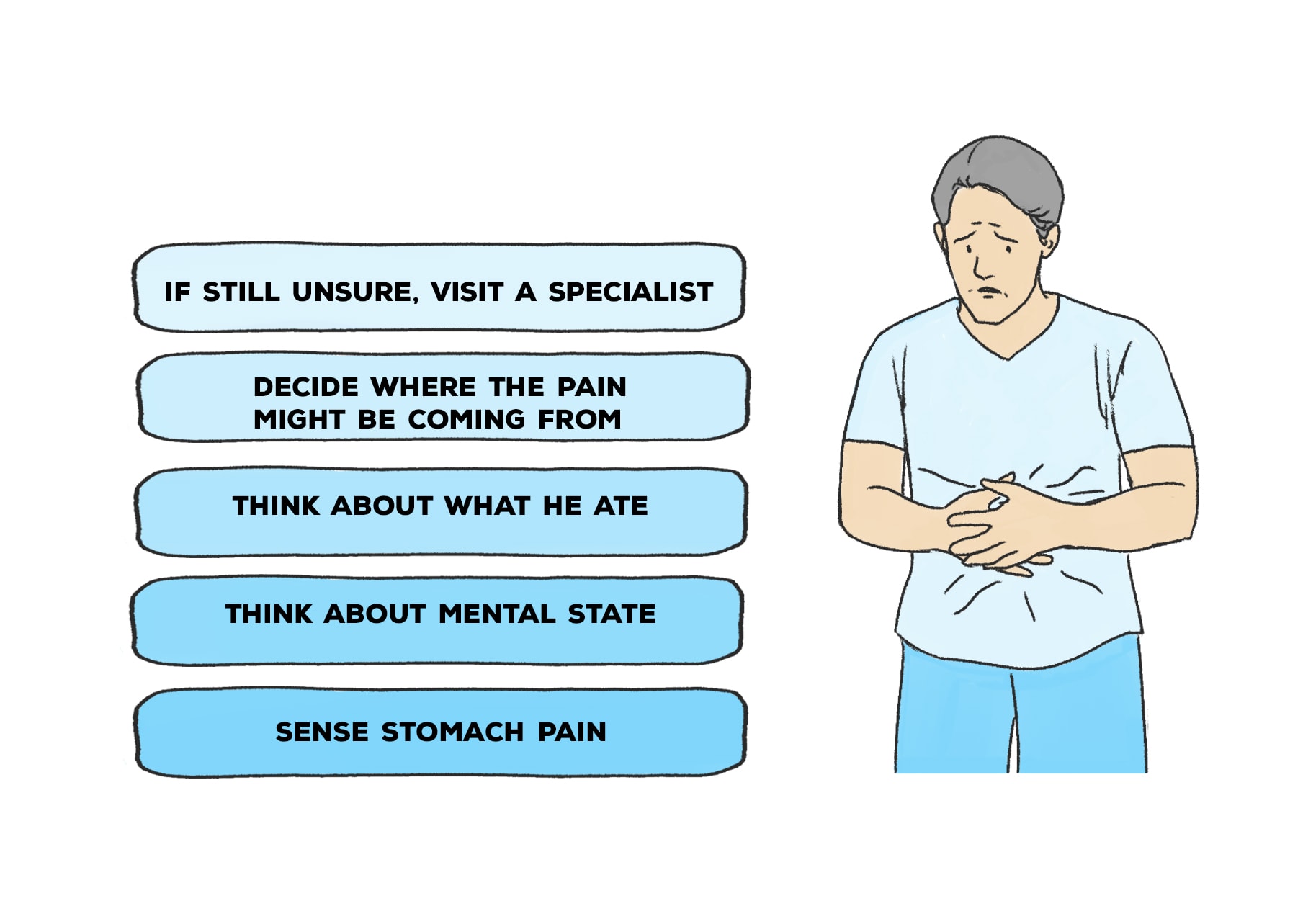

7) Strange Stomach Pains

Have you suddenly felt strange stomach pains “out of nowhere?” You must use bottom-up processing to figure out what is causing your symptoms. The first clue that something is not right is your sensory experience. From there, you have to think about how you are feeling mentally or if you ate something that could have caused the stomach pains.

You have to draw from past experiences where you might have felt similarly. If you anticipate stomach pains due to an allergy or situation that may cause stomach pain, you may be using top-down processing to assess your symptoms.

To summarize the idea of bottom-up processing, James Gibson proposed a theory saying that analyzing stimuli is a direct line between the stimuli around us and the parts of the brain that analyze it. No further learning influences what we perceive.

Here are some more examples of bottom-up processing:

- Reading a Book - Recognizing individual letters and words before understanding the meaning of a sentence or paragraph.

- Puzzle Solving - Fitting individual pieces together based on their shapes and colors before seeing the complete picture.

- Hearing a Sound - Recognizing the basic tone or pitch before identifying it as a specific instrument or voice.

- Tasting Food - Sensing basic flavors (sweet, salty, sour, bitter, umami) before identifying the specific dish or ingredient.

- Touching an Object - Feeling the basic texture (smooth, rough, soft, hard) before recognizing what the object might be.

- Seeing a Painting - Noticing individual colors and strokes before understanding the overall scene or emotion conveyed.

- Listening to Music - Hearing individual notes before recognizing a melody or song.

- Watching a Dance - Observing specific movements and steps before understanding the story or emotion of the performance.

- Smelling a Scent - Detecting basic olfactory components before identifying it as a specific flower, food, or perfume.

- Walking in Nature - Noticing individual plants, animals, or sounds before appreciating the entire ecosystem.

- Looking at a Crowd - Seeing individual faces before recognizing a familiar person or understanding the group's mood.

- Feeling Pain - Sensing a sharp or dull sensation before identifying the cause or source of the discomfort.

- Observing a Magic Trick - Watching the individual actions of the magician before understanding the trick as a whole.

- Watching a Film - Noticing specific actors, colors, or sounds before understanding the plot or theme.

- Reading a Map - Identifying individual landmarks or roads before understanding the layout of a city or region.

- Looking at a Mosaic - Seeing individual tiles or pieces before recognizing the overall image or pattern.

- Hearing a Language - Recognizing individual words or sounds before understanding the meaning or context of a sentence.

Is Bottom Up Processing Automatic?

While it may feel like we interpret road signs, make assumptions, or read images automatically, some work goes into bottom-up processing. Of course, these skills get much faster as we interact with the world around us!

For example, basic perceptual processes like color vision and motion detection occur automatically and without conscious effort. These processes involve relatively simple neural pathways that can quickly identify certain perceptual inputs and respond accordingly.

On the other hand, higher-level cognitive processes related to learning, memory formation, problem-solving, and language comprehension require conscious effort and cannot be classified as automatic responses.

It has also been suggested that some types of bottom-up processing could become automated with practice; for instance, if a person needs to recognize a particular pattern to complete a task, they may eventually develop an unconscious habit of recognizing this pattern over time. This suggests that top-down expectancies play an important role in shaping our responses to stimuli even when we rely primarily on lower-level data-driven mechanisms at first glance. Therefore although bare bottom-up perception might be considered automatic, it appears likely that many more complex upper-level functions will remain subject to voluntary control even after extensive training or experience.

Is Bottom-Up Processing The Same As Inductive Reasoning?

Many students confuse bottom-up processing with inductive reasoning - but they aren't the same! Inductive reasoning and bottom-up processing are often linked because they take from past information and experiences. Still, it's important to know they are similar means to a different end.

Take a look at what Brainvoyager135 shared when this question was asked on Reddit:

"It's not a bad way to help you memorize the concept, since connecting is important. However processing and reasoning are not synonymous. Processing is all about sensation and perception. Reasoning is about theories and observations."

Uses for Bottom-Up Processing in Everyday Life

Bottom-up processing is a method of understanding that starts with analyzing individual components and gradually builds up to larger concepts. This type of information gathering is used frequently in everyday life, especially when dealing with complex tasks such as problem-solving.

For example, a student trying to solve a math equation may start by breaking down the problem into smaller parts and building on those smaller pieces until they arrive at an answer.

By dissecting each piece one at a time, the student can focus on one element without being overwhelmed by the data presented in the question. Once they have solved each small portion, they can work towards finding an overall solution to the entire equation.

In addition to educational pursuits, bottom-up processing is useful when making decisions or forming opinions about topics like politics or current events. In this case, rather than immediately jumping to conclusions based on initial impressions or summaries from others, people can use bottom-up methods to independently research issues in depth before forming any judgments.

This helps create more informed opinions that are not influenced by outside sources but instead stem from personal investigation and evaluation.