Amy Cuddy is an American social psychologist, lecturer, public speaker, and best-sellling author. She specializes in the behavioral science of prejudice, presence, and power. Cuddy is best known for her work on “power posing” and the Stereotype Content Model (SCM). She currently works with the World Economic Forum, teaches in the executive education program at the Harvard Business School, and is one of the most influential voices in the field of social psychology today.

Amy Cuddy's Childhood

Amy Joy Casselberry Cuddy was born on July 23, 1972, in Robesonia, Pennsylvania. She was raised in a working-class family. As a child, Cuddy enjoyed swimming at the community pool, throwing seed corn at houses on Halloween, and watching the fireworks on the Fourth of July. When reflecting on her childhood, she stated that she loved the simplicity of growing up in a small town.

At age five, Cuddy was drawn to ballet primarily because she wanted to wear a tutu. However, she soon wanted to learn as much about dance as she could. She first attended Linda Petsu’s School of Dance in Wolmelsdorf. When she was about ten years old, she started classes at Berks Ballet Theatre in Reading, Pennsylvania.

Cuddy attended the Conrad Weiser High School. She was a brilliant student. Her teachers thought of her as a determined, generous, and independent person who was willing to explore new ideas. Cuddy’s third grade teacher—Elsa Wertz—recommended her for the Conrad Weiser gifted program.

As a small town girl from a humble background, Amy Cuddy knew the value of hard work. She also learned how to make the most of what she had. During her high school years, she held a number of jobs while attending school. These jobs included working at McDonald’s, a local flower shop, and the Jesuit Center for Spiritual Growth at Wernersville.

Educational Background

After graduating from high school in 1990, Amy Cuddy enrolled at the University of Colorado. She chose to study theatre and American History. Cuddy also took her ballet dancing very seriously. She worked as a roller skating waitress at the L.A. Diner to pay for her college tuition.

During her sophomore year in 1992, Cuddy was involved in a serious car accident. It happened on a night when she and some college friends were returning from a trip to Montana. The friends had decided to take turns driving, but after Cuddy fell asleep in the back seat, the driver eventually nodded off as well. They were traveling at 90 miles per hour when the car veered off the road and rolled over three times. Cuddy was thrown out of one of the side windows.

When Amy Cuddy woke up, she was in the hospital. The doctors told her that she had sustained severe head trauma and diffuse axonal injury. Her IQ dropped by 30 points and she needed physical therapy, occupational therapy, cognitive therapy, and speech therapy. Although her doctors eventually declared that she was “high-functioning” they also believed it was unlikely she would be able to finish college.

At 19 years old, Amy Cuddy felt powerless. She believed she had lost her identity. She knew herself to be a smart person. However, her brain injury left her struggling to follow her university lectures as she was not able to read and process information as she did before. She tried to go back to school several times, but had to drop out. Even her friends told her she became a different person after the accident.

However, Cuddy’s academic journey was not over. She thought hard work would help her brain to heal so she decided to take some time off from school to “relearn how to learn.” Cuddy was determined to finish college, especially as she was the person paying for it. She devoted herself to her studies and regained her IQ and dancing ability in two years.

Amy Cuddy returned to the University of Colorado in 1994. This time, however, she wanted to study neuroscience as her brain injury had sparked an interest in that subject area. Cuddy eventually completed her bachelor’s degree in psychology and graduated magna cum laude in 1998—eight years after she first enrolled at the institution. She married her first husband on the day of her graduation but they got divorced a few years later.

After leaving the University of Colorado, Cuddy took a job as a research assistant to Susan Fiske, PhD, at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. It was an unpaid position that focused on social psychology. Cuddy was willing to work for free because she still felt as if she was lagging behind and wanted to prove that she could succeed academically. The field of social psychology was an excellent fit for her as it appealed to her passion for social justice

When Fiske accepted a position at Princeton in 2000, she brought Cuddy with her as a PhD student. However, Cuddy was intimidated by the environment because she had a brain injury and did not have a fancy pedigree. Cuddy says she felt like an imposter who was not smart enough to attend Princeton. When she had to give her first public talk as a PhD student, she felt like quitting the school because she was afraid other people would find out she wasn’t Princeton material.

When Cuddy told Susan Fiske that she felt like giving up, her mentor was very supportive. Fiske encouraged her to stay at Princeton and “fake it till you make it.” Cuddy used her personal insecurities as motivation to work harder than her peers. Over time, other students began to seek advice from Cuddy when they needed help with personal or academic issues.

Amy Cuddy received her master’s degree in social psychology in 2003. She earned her PhD in social psychology in 2005. The title of her dissertation was “The BIAS Map: Behavior from intergroup affect and stereotypes.” In her paper, Cuddy examined how people form judgments of others.

After Cuddy graduated from Princeton, she became an assistant professor of psychology at Rutgers University. In 2006, she joined the staff at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University. Two years later, Cuddy joined the faculty at the Harvard Business School.

The Stereotype Content Model

The Stereotype Content Model (SCM) is a social psychology theory proposed by Cuddy and her colleagues (Susan Fiske, Peter Glick, and Jun Xu) in 2002. According to this model, people form judgments of others along two dimensions: warmth and competence. Warmth relates to the perceived intentions (whether positive or negative) of members of the outgroup in relation to members of the ingroup. Competence has to do with the ability of outgroup members to carry out those intentions.

People judged high on warmth are considered friendly, sincere, trustworthy and good-natured. Those judged high on competence are thought to be skillful, intelligent, confident and efficient. Social groups may be judged as being high on both dimensions, low on both dimensions, or may receive a mixed judgment, where they are rated high on one dimension but low on the other.

According to the SCM, judgments of warmth are influenced by perceived competition for valued resources, with higher competition predicting lower judgments of warmth. Appraisals of competence are influenced by the relative status of the outgroup, with higher status predicting higher perceptions of competence.

Ongoing research has shown that the two content dimensions proposed by the SCM are consistent across various cultures. In other words, all cultures studied thus far have been found to distinguish social groups on the basis of warmth and competence. For some social groups, perceptions of warmth and competence remain fairly stable across cultures. For example, the elderly and people with disability are consistently judged as high in warmth but low in competence. Judgments of other groups, however, may vary considerably depending on the socio-political context.

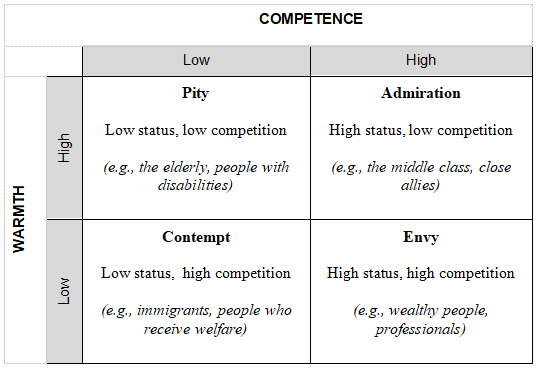

The SCM also proposed that there are distinct emotions associated with the four competence-warmth combinations. These emotions are shown in Table 1 below, along with examples of social groups commonly viewed as belonging to each category.

Table 1. Emotions and examples of social groups associated with the four combinations of warmth and competence

As shown in the table above, people viewed as warm and competent (usually members of the ingroup and their allies) tend to be admired. These individuals evoke feelings of pride and are treated positively. On the other hand, groups that are judged as cold and incompetent are likely to be viewed with contempt or disgust. Members of these groups may be neglected, treated harshly or even harmed.

People who are perceived as warm but incompetent tend to evoke feelings of pity and sympathy. These individuals may receive assistance and protection but are just as likely to be neglected. Groups that are competent but cold are most likely to elicit feelings of jealousy and envy. Although they possess abilities that are highly valued, they offer no advantages to the ingroup and are generally regarded as a threat.

Power Posing

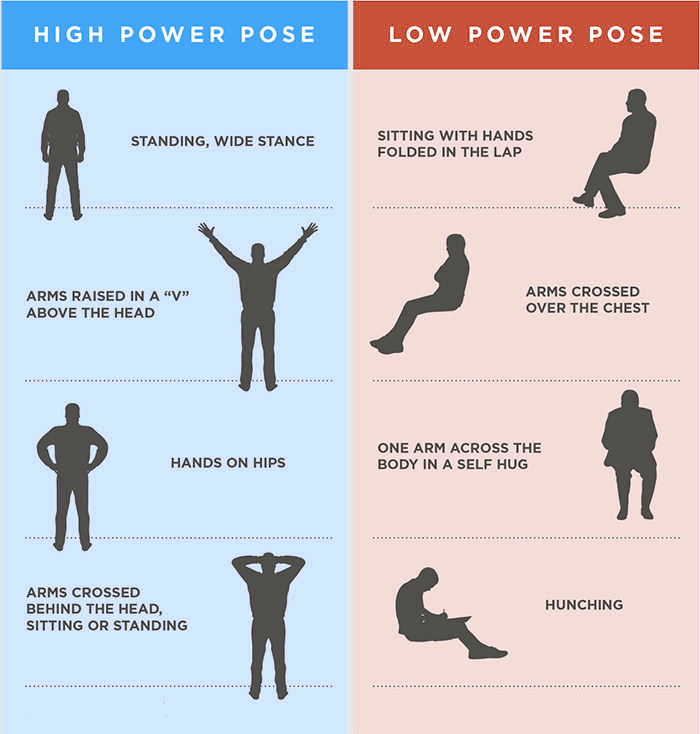

The concept of ‘power posing’ emerged from a 2010 study conducted by Cuddy and two of her colleagues, Dana Carney and Andy Yap. The researchers sought to investigate the physiological, emotional and behavioral effects of adopting gestures commonly associated with power (i.e., power poses). In short, the researchers wanted to find out if adopting brief power poses could stimulate hormonal changes, causing one to feel and act ‘powerful.’

The experiment included 42 participants (26 women and 16 men) who were randomly assigned to one of two conditions - high power poses or low power poses. The two types of poses differed along two dimensions which the researchers identified as being consistently linked to power. The first dimension, expansiveness, relates to the amount of space taken up by the individual, while the second dimension, openness, deals with the position of the individual’s limbs, whether they are kept open or closed. High power poses take up more space and are more open than low power poses.

Participants in the high power pose group were asked to sit tilted back in a chair with their hands behind their head, and their feet propped up on a desk. Next, they were asked to stand behind the desk, leaning forward on it with their hands. In the low power pose group, participants sat with their arms held very close to their bodies and hands folded in their laps. They were then asked to stand with their hands and legs tightly crossed.

Three different variables were measured by the researchers:

- Hormonal changes - specifically, changes in testosterone and cortisol levels.

- Risk tolerance - participants were each given $2 which they could either keep or use to gamble.

- Feelings of power - participants were asked to rate how powerful they felt on a scale of 1 to 4.

The first two variables were chosen based on pre-existing research which suggests that power and dominance are associated with higher testosterone and lower cortisol levels, as well as an increased willingness to take risks.

Participants in the high power pose group experienced a greater increase in testosterone and decrease in cortisol than those in the low power pose group. The high power posers also reported feeling more powerful and “in charge” than those in the low power pose group, and were more likely to take financial risks.

Based on the findings of the study, Cuddy and her colleagues concluded that brief, simple changes to one’s physical posture may be enough to improve confidence and performance in difficult situations. The idea is that by pretending to be powerful (ie.,by adopting postures typical of powerful people) one can actually start to feel powerful.

The original paper written by the researchers became one of the most commonly cited articles in the psychology literature and Cuddy’s TED talk on the subject of power posing is one of the most popular TED talks on YouTube today.

Applications of Amy Cuddy’s Theories

Although she was not the lead researcher for the original study on power posing, Amy Cuddy has since emerged as the foremost proponent of this tactic. Through her many talks, public appearances and self-help book, she promotes power posing as a means of overcoming feelings of powerlessness caused by a lack of resources or low social status. Cuddy also suggests that power posing can be used to increase confidence and enhance performance in a number of stressful situations. These include job interviews, public speaking, business negotiations and courtroom appearances.

Interestingly, additional research by Cuddy and her colleagues revealed that power poses do not have to be adopted during a stressful situation to have an effect; they can be just as effective when used in preparation for that event, for example, when preparing for an interview or a public appearance.

Other areas where power posing might be beneficial include:

Sports - power posing can be integrated into a team’s warm-up routine or when preparing for high-stress situations like taking a penalty kick

Counseling and therapy - power posing can be taught in therapy as a strategy for overcoming feelings of depression, anxiety and helplessness. It can also be used to assist victims of bullying and domestic abuse.

Social interactions - power posing can help to improve the ease, confidence and authority with which one communicates in social settings, as well as reduce anxiety in unfamiliar social situations, for example, when on a blind date.

Healthcare - power posing may have some value in helping patients with pain management. Preliminary studies suggest that adopting high power poses increases one’s tolerance for pain.

The Stereotype Content Model also has several real world applications. At the most basic level, the model helps to predict and explain instances of prejudice, social discrimination and inter-group conflict. It can also be used as a framework for developing interventions aimed at reducing discrimination.

Studies have shown, for example, that people with disability are consistently judged as high on warmth but low on competence. This perception of incompetence promotes inequalities and discrimination. By increasing perceptions of competence (e.g., through involvement in sports and other forms of physical activity), it may be possible to reduce prejudice and discrimination toward these individuals.

The Stereotype Content Model has also been used to explain judgments of, and attitudes toward, inanimate objects, such as products and brands. It has been suggested, for example, that if people perceive a particular brand or company as being high on both warmth and competence, they will be more likely to trust and support that brand or company. Business owners and brand managers can use this knowledge to their advantage when promoting goods and services.

Criticisms of Amy Cuddy’s Theories

Despite the widespread appeal of Cuddy’s “fake it till you make it” philosophy, numerous critics have raised doubts about the purported benefits of power posing. A major reason for this is that other researchers have not been able to replicate the results of the original study. For example, researchers at the University of Zurich (UZH) adopted the same procedure with a much larger sample than that of Cuddy and her colleagues, but obtained different results.

In the UZH study, participants in the high power pose condition did report feeling more powerful than those in the low power pose group. However, no effects were found on risk-taking or on testosterone levels. In fact, those in the high power pose group actually had slightly lower levels of testosterone than those in the low power pose group - the exact opposite of what Cuddy and her colleagues had found.

Cuddy’s group responded to this criticism by citing several other studies demonstrating the effects of power posing. However, none of these studies measured hormonal changes, which had been central to their original hypothesis. The emphasis in these other studies was largely on psychological effects.

In 2016, mounting evidence against the findings of their study led one of the researchers, Dana Carney, to publicly withdraw support for the power posing hypothesis. She also admitted that data from the original study had been statistically manipulated in ways that made the results appear more significant than they really were.

The original power posing study has also been criticized for methodological flaws. For example, some researchers have pointed out that high power poses were only compared to low power poses and not neutral poses. According to these critics, the differences observed in the study may actually have occurred because low power poses make one feel worse than before and not necessarily because high power poses make one feel better. The inclusion of a neutral comparison group would have helped to clarify the results.

Despite the flaws associated with the original power posing study, there are numerous personal accounts suggesting that power posing works. The science behind the practice is clearly debatable, but given its appeal and simplicity, it will likely remain a popular life-hack for many years to come.

In contrast to power posing theory, the Stereotype Content Model has been found to be quite robust across several studies and cultures. However, a few modifications to the original model have been suggested. For example, subsequent research suggests that the warmth dimension actually consists of two distinct variables, namely sociability and morality. Sociability has to do with how friendly and open people are, while morality relates to their moral and ethical character (e.g., are they honest, loyal and trustworthy). A revised model consisting of three dimensions (competence, sociability and morality) has therefore been proposed.

Amy Cuddy's Books, Awards and Accomplishments

Amy Cuddy has authored one book and several academic papers over the course of her career. In 2015, she published the self-help book Presence: Bringing Your Boldest Self to Your Biggest Challenges. This book advocates power posing and self-trust. It has been translated into 32 languages and claimed the #3 spot on The New York Times Best Seller list in 2016. Cuddy’s second book, Bullies, Bystanders, and Bravehearts is expected to be published in 2021.

Some of Cuddy’s most significant academic papers are listed below:

- Cuddy, A. J. C.; Glick, P.; Beninger, A. (2011). "The dynamics of warmth and competence judgments, and their outcomes in organizations". Research in Organizational Behavior. 31: 73–98. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.250.9367. doi:10.1016/j.riob.2011.10.004.

- Carney, D.; Cuddy, A. J. C.; Yap, A. (2010). "Power posing: Brief nonverbal displays affect neuroendocrine levels and risk tolerance". Psychological Science. 21 (10): 1363–1368. doi:10.1177/0956797610383437. PMID 20855902., listed among "The Top 10 Psychology Studies of 2010" by Halvorson (2010).

- Cuddy, A. J. C., Fiske, S. T., & Glick, P. (2008). Warmth and competence as universal dimensions of social perception: The Stereotype Content Model and the BIAS Map. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (vol. 40, pp. 61–149). New York, NY: Academic Press.

- Cuddy, A. J. C.; Fiske, S. T.; Glick, P. (2007). "The BIAS Map: Behaviors from intergroup affect and stereotypes". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 92 (4): 631–648. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.92.4.631. PMID 17469949.

- Fiske, S. T.; Cuddy, A. J. C.; Glick, P. (2007). "Universal dimensions of social cognition: Warmth, then competence". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 11 (2): 77–83. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.005. PMID 17188552.

- Fiske, S. T.; Cuddy, A. J. C.; Glick, P.; Xu, J. (2002). "A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from status and competition". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 82 (6): 878–902. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.878. PMID 12051578.

Cuddy has also received a number of awards for her academic accomplishments and contributions to the field of social psychology. A few of these awards include:

- 100 Women of 2017, BBC

- Game Changer, Time

- 50 Women Who Are Changing the World, Business Insider

- World’s Top 50 Management Thinkers, Thinkers50

- Top 50 Leadership Innovators Changing How We Lead, Inc.

- Top 5 HR Thinkers, HR Magazine

- 100 Science Stars on Twitter, Science

- Ten Bostonians Who are Upending the Way We Live, Lead, and Learn, Boston Magazine

- Rising Star, Association for Psychological Science

- Early Career Award, Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues

- Harvard Excellence in Teaching Award, Harvard University

- Young Global Leader, World Economic Forum

Personal Life

Amy Cuddy’s highly cited research has been published in some of the top academic journals in the world, including the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), Science, and Psychological Science. Her work has also been featured in the Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, Guardian, Fast Company, The Economist, Wired, NPR, BBC, and many other trusted publications. Cuddy’s viral TED talk made her an internet sensation overnight. After giving the talk, she was offered a book deal and appeared on a number of popular television shows such as the Late Show with Stephen Colbert, CBS Sunday Morning, 60 Minutes with Charlie Rose, Good Morning America, BBC World News, and CNN with Anderson Cooper.

Of course, increased media attention led to increased scrutiny, especially from her colleagues in academia. Many onlookers believe the criticism of Cuddy’s research on power posing seemed excessive, malicious, and personal. Even so, many people have expressed their appreciation for her work. Among them are athletes, students, actors, retirees, politicians, victims of sexual assault, people with mental health issues, and people with physical limitations.

Cuddy still teaches executive education at Harvard Business School. She also works with the World Economic Forum and is the co-founder of the Citizen Confidence Project. Cuddy is a big fan of live music. In 2014 she was inducted into the Conrad Weiser Hall of Fame.

During her second year at Princeton, Cuddy had a son named Jonah. In August 2014, she married Australian data science analyst Paul Coster in Aspen, Colorado. Interestingly, Cuddy remarked that she first met Paul because of a particular picture he had taken of himself. The picture showed a closeup of Paul striking an exaggerated open-legged power pose while wearing bright blue pants.

References

Altmann, J. (2014, April 2). Power to the people. Princeton Alumni Weekly. Retrieved from https://paw.princeton.edu/article/power-people

Amy Cuddy. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://thinkers50.com/biographies/amy-cuddy/

Amy J.C. Cuddy, PH. D. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.amycuddy.com/

Cuddy, A. J. C., Wilmuth, C. A., Yap, A. J., & Carney, D. R. (n.d.). Preparatory power posing affects nonverbal presence and job interview performance. Retrieved from http://faculty.haas.berkeley.edu/dana_carney/pp_performance.pdf

Dominus, S. (2017, October 18). When the revolution came for amy cuddy. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/18/magazine/when-the-revolution-came-for-amy-cuddy.html

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., Glick, P., & u, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(6), 878-902.

Iowa State University. (2019, October 1). No evidence that power posing works. ScienceDaily. Retrieved from www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/10/191001110824.htm

Jordan-Young, R. M., & Karkazis, K. (2019). Testosterone: An unauthorized biography. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kegel, S. (2016). The stereotype content model: Using a social psychology theory as a framework for user experience work and brand perception. Retrieved form https://uxdesign.cc/the-stereotype-content-model-a-social-psychology-theory-as-a-framework-for-brand-perception-and-affc5b26532d

Lambert, C. (2010, November). The psyche on automatic. Harvard Magazine. Retrieved from https://harvardmagazine.com/2010/11/the-psyche-on-automatic

Scheid, L. (2016, July 17). Body language expert amy cuddy describes her childhood roots. Retrieved from https://workingwomanreport.com/body-language-expert-amy-cuddy-describes-childhood-roots/