Are you a psychology student wanting help putting the Atkinson and Shiffrin model of memory into your long-term memory? You've came to the right place! In this article, my goal is to provide you with everything there is to know about the Multi-Store model of memory.

What Is the Atkinson and Shiffrin Model of Memory?

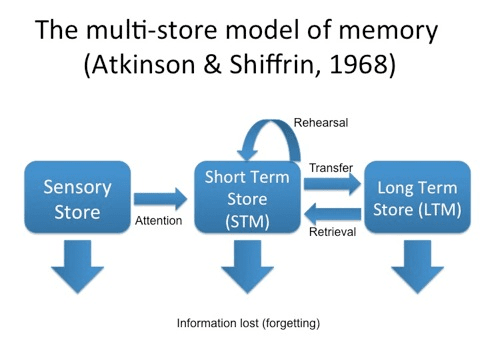

Atkinson and Shiffrin’s Model of Memory consists of three locations where we store memories: our sensory memory, short-term memory, and long-term memory. Learning about this memory model will help you understand how your brain works to create memories and how you can ensure that the things you need to remember to end up in your long-term memory.

Curious Cases of Short-Term and Long-Term Memory

Memory is tricky. It's something that we don't always think about until our memory starts to fail or we interact with someone who has a poor memory. Did you ever watch the romantic comedy 50 First Dates? In the movie, Drew Barrymore plays a woman who has lost her short-term memory loss due to a car accident that caused a TBI. Every morning, Barrymore's character “resets” and thinks that she is waking up to the day of the accident. This is a case of anterograde amnesia, and it does reflect the lives of people living with this condition.

(Interested in learning about people with significant cases of amnesia? Read about Clive Wearing and others here.)

For many people, characters like this first teach you about short-term vs. long-term memory. But are these actual parts of your brain? Can you lose short-term memory loss and end up stuck like Drew Barrymore’s character in 50 First Dates?

These are some of the questions that Richard Atkinson and Richard Shiffrin were asking as they conducted experiments in memory storage. (Although they were in the field at least 30 years before 50 First Dates came out.)

Who Are Atkinson and Shiffrin?

Each of these psychologists has a prestigious background in psychology and other sciences. Richard Atkinson, for example, received his Ph.D. in experimental psychology and mathematics at Indiana University Bloomington. Shortly after, he joined the staff at Stanford University, where he met Richard Shriffin. In 1968, Shiffrin was just finishing up his Ph.D. in Mathematical Psychology. The two created the Multi-Store Model of Memory that year. (You can really see their math backgrounds in the model!)

After creating this model of memory, both men went on to have outstanding careers. Richard Atkinson went on to serve as the President of the National Science Foundation. Shiffrin continued to teach at Stanford and Indiana University Bloomington. He extended the multi-share model of memory to the Search of Associative Memory (SAM) model and later the Retrieving Effectively From Memory (REM) model.

Their model of memory has undergone scrutiny but remains a significant theory of memory storage and retrieval.

About the Three Elements in Atkinson and Shiffrin's Multi-Store Model of Memory

1) Sensory Memory

Duration: Up to 4 seconds

Capacity: Limited to the information from sensory organs

Encoding: Different stores for each sense

Take a moment to look at what is around you. Listen to the sound of the birds chirping outside or any other background noises. Smell and taste whatever is present. Feel your hands on your desk or your feet on the floor. This is a lot of information to take in! To the brain, every smell, taste, sight, etc. is like a single data point.

All of the data you just collected is sensory input.

Sensory input travels through the auditory system, visual system, etc. into our sensory memory. Everything we hear, touch, feel, see, smell, taste - it may all end up in our long-term memory at some point. But most of it will be released and forgotten here. Our sensory memories can hold a lot of information, but only for a very short period of time. How short? It depends on which sense we used to gather that information.

Most information, including sight information, stays in sensory memory for up to half a second.

Further studies on echoic memory, or the collection of things that we hear, can last for up to four seconds.

Once that time has passed, the most important data (and the data you gave your attention to) has moved to short-term memory storage.

When we attend to information, then our brain knows to pop it into short-term memory storage. This is where attention is important.

I told you to take into account your sight, the sounds you heard, etc. You have told yourself that the information in this video is important enough to remember. That’s all it takes for the memory to head farther along into your memory.

2) Short-Term Memory Storage (STM)

Duration: Up to 18 seconds, can be longer with rehearsal

Capacity: The magic number of 7 plus or minus 2.

Encoding: Mostly auditory memory (You remember by repeating in your head)

Now we’ve started to narrow down the information to what is important. But short-term memory storage isn’t as large as sensory memory storage. Our short-term memory can only handle seven items of information at once. (Give or take one or two things.)

If you are given a list of things to remember, maybe a list of names or items to buy at the store, the first and the last items on the list are going to stick out the strongest in your short-term memory. After you read the list to yourself, you are most likely to recall those last few items first.

The primacy effect is the idea that the first things on a list are more likely to be remembered than the middle items.

The idea that the last items on a list are easily remembered is called the recency effect.

The serial position effect is a theory that serves as an umbrella theory for both of these effects.

Repetition and Coding Short-Term Memory to Long-Term Memory

But items only stay in short-term memory for up to around 18 seconds. The stuff that is important makes its way to long-term storage. The stuff that isn’t important is dropped. You might be asking, how can I guarantee that the items in my short-term memory make it to my long-term memory?

The answer is simple: repetition. At least, that's what Atkinson and Shiffrin believed. Repeat the items you need to remember over and over again. If you are trying to remember a list of things in no particular order, switch up the order and repeat them to yourself again and again. Say things out loud as you write them down if you have to.

Atkinson and Shiffrin called this a "rehearsal loop". Studying is a great form of this and allows students to move short-term memory into long-term memory.

They also note that repetition is one of two ways to store memories, but repetition is mentioned more in criticisms of their work. Atkinson and Shiffrin also mention "coding" as a way to convert short-term to long-term memories.

3) Long-Term Memory

Duration: Unlimited

Capacity: Unlimited

Encoding: Semantic (We remember the meaning of information)

The things that our brain has considered to be most important, most likely things we have repeated to ourselves over and over again, head to our long-term memory storage.

We can store an unlimited amount of information in long-term memory, for an unlimited amount of time. Think back to your earliest memory. It certainly stayed in your memory for longer than 18 seconds!

There are many different ways to increase the likelihood of remembering something, as well as testing long term memory, but cognitive psychologists still don't really understand how the entire process takes place. All we can do is guess and make models with hypotheses right now.

This Is a Simplistic Model

The Atkinson-Shiffrin Model is an easy one to remember, but it doesn’t tell the entire story of how people remember things.

Not all information, whether it appears important at the time or not, ends up in short-term memory and stays in the long-term memory. Of course, this model also fails to address how we lose some of our memories.

Here’s the biggest takeaway from this lesson: our short-term and sensory memories don’t last long. Our short-term memory storage isn’t unlimited. If you are determined to remember something, give it a priority. Repeat it. Write it down and audibly repeat it again.

Keep this model stored in your long-term memory, but don’t neglect the findings that other studies have revealed since Atkinson and Shiffrin.

Criticisms and Responses to Atkinson and Shiffrin Model of Memory

Working Memory

One criticism about Atkinson and Shiffrin's three-part model has to do with the space between sensory memory and short-term memory. In 1974, Baddeley and Hitch came up with a Working Model of Memory that expands upon the simplistic short-term memory storage process and explains how we hold smaller pieces of information in our brain.

Take the idea of memorizing a phone number. We take in the sound or sight of 7-10 digits, sing it to ourselves a few times, and then write it down or type it out or do what we need to do with that phone number. Once that process is done, we focus our attention on other things. The memory of the phone number may be gone once we shift our focus. How do we explain that? Short-term memory? Sensory memory? Where does that phone number go while we're working with it?

Baddeley and Hitch say "working memory."

Levels of Processing Model

There are people who can remember things without a need for repetition. Have you ever remembered something that happened to you years ago, that appears totally random? Or do you experience something once and know you'll remember it forever, without intentionally trying to store it in your long-term memory? These questions encouraged many psychologists to look beyond Atkinson and Shiffrin's idea of repetition as a memory storage tool.

Additional studies show how you take a more active role in storing information long term aside from general repetition. If you are interested in learning more about this, look up Craik and Tulving’s work on the Levels of Processing Model from the 1970s. The levels-of-processing model suggests that memories "encoded" in a more semantic process are more likely to make their way into long-term memory.

Tulving went further to categorize different types of long-term memories. Episodic, procedural, and semantic memories are all stored differently. Various cases of memory loss, in which people can remember how to brush their teeth but not their father's birthday, show how possible it is that these memories are stored in different places.

Theories of Memory Continue to Evolve

The Atkinson and Shiffrin Model of Memory is a significant, but just one theory that attempts to explain the weird and wacky processes of storing and recalling memories. Their model isn't the end-all, be-all of memory models, but it provides some great groundwork for more complicated theories that follow.