Have you ever been at a cocktail party - or any situation with many people talking in the background - and wondered how you could still hear the person you’re talking to?

How, with all of these other people talking in the background, can you decipher what I am saying to you right now? A big jumble of varying words and sounds is entering your ears all at once, and yet you are still able to understand me.

What is the Cocktail Party Effect?

This human ability to understand a conversation, even with many distracting sounds and side conversations happening in the background, is known as the “Cocktail Party Effect,” it has baffled psychologists for years. It's also called "selective auditory attention" or "selective hearing."

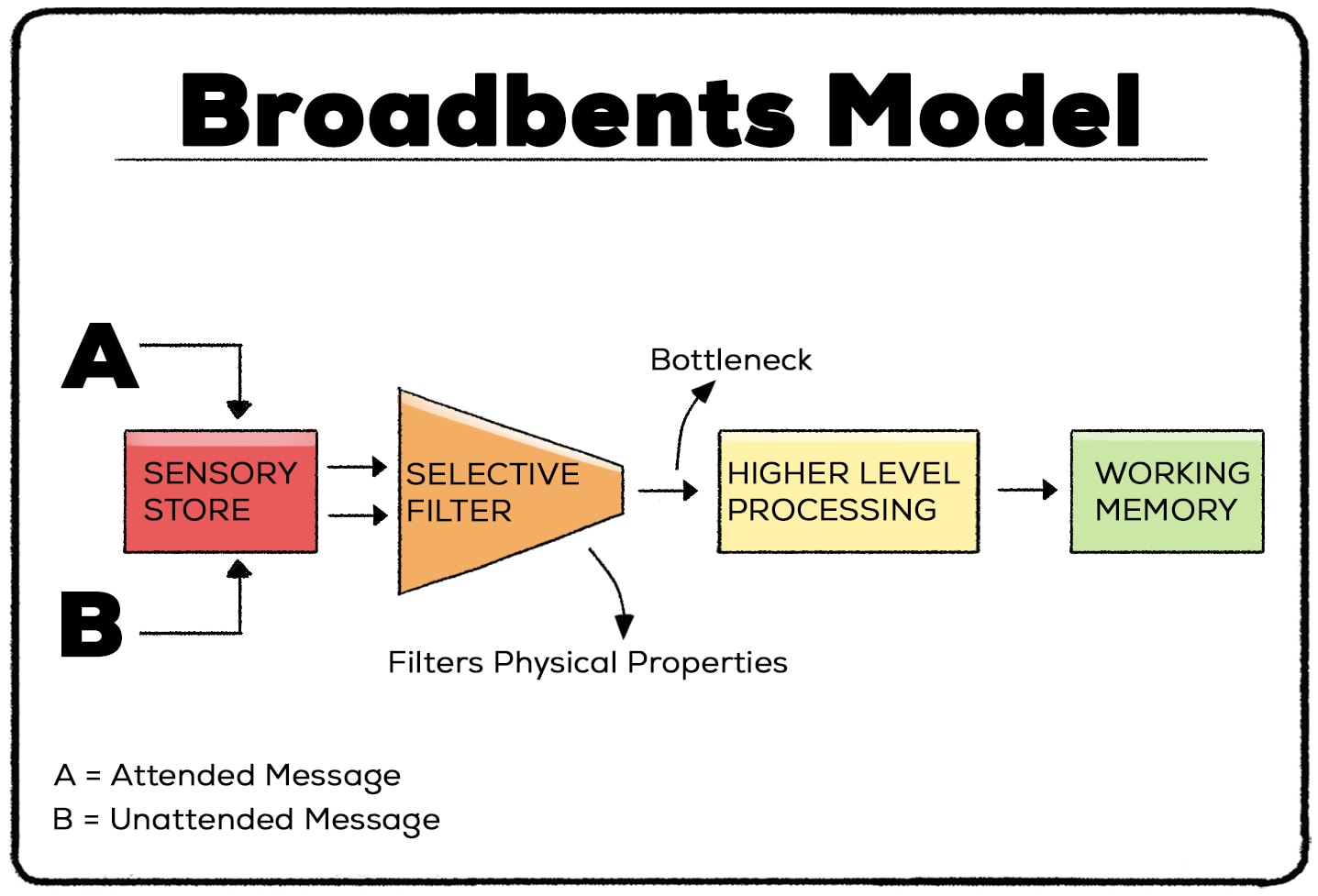

Psychologist Donald Broadbent created a model that shows how our brain filters out the stimuli that it will not pay attention to. Broadbent believed that if the brain decided that the stimuli were not important, it was filtered out. Tone, volume, and other physical characteristics provided the criteria for what our brain thought was worthy of our attention.

Bradbent's Attention Model seems to break down regarding the Cocktail Party Effect.

This effect was first discovered to be a problem in the 1950s when air traffic controllers struggled to hear messages from multiple pilots talking simultaneously. In 1953, an MIT paper by a British psychologist named E. Colin Cherry came out where Cherry described this effect as the “cocktail party problem.”

In that MIT paper of 1953, it was theorized that there were five potential ways that a human could separate the voice of the person they were talking to from the voices of surrounding conversations:

- The direction the voice is coming from

- Body language (gestures, lip-reading, etc.)

- Differences in speaking voices (pitch, speed, male vs. female, etc.)

- Differences in accents

- Transition probabilities (you’ve heard some words, so you can infer the transition words you missed based on probabilities and context)

Scientists like to focus on just one variable at a time when doing experiments, so the researchers at MIT decided to focus on just that last aspect for their first study. To do this, they recorded two messages from the same talker on magnetic tape and played them back to their subjects wearing headphones.

Experimenting this way effectively nullified those first four variables. The end product of doing that sounded like an incomprehensible babel, but subjects could still hear the two different messages when they focused on one of them. Psychologists considering this study suggested that humans are very good at memorizing the transition properties of words in sentences, which makes it easy for us to predict word sequences.

In short, this study gives us some evidence to answer the cocktail party problem - perhaps we can focus in on one message among many because we are good at using context and our knowledge of language to predict the words we didn’t hear.

So what about those other four potential reasons that we listed earlier? Well, let’s go through them, one at a time:

The direction the voice is coming from

In follow-up experiments considering the cocktail party effect, researchers had their subjects listen to two different messages in a new way. They had their subjects wear special headphones that sent one message into the right ear and the other into the left ear. This created differences in the directions the voices were coming from.

Most subjects struggled to ignore voices from one ear when told to focus on the voice coming into another.

This result implies that the direction a voice is coming from is not a factor that we consider very significantly.

The subjects would not have struggled to separate the audio so much if the direction of the audio had been a significant factor.

Body language (gestures, lip-reading, etc.)

Body language goes along with transition probabilities. We saw earlier that predicting words via contextual clues in our language is a good method for us to gain an understanding of a sentence, and body language is a good indicator of context. Therefore, it’s not much of a leap to say that the context we gain from viewing body language helps us to piece together our predictions for sentences, even when we don’t hear every word that was spoken.

Reading the body language of a speaker is an important factor when predicting words.

Differences in speaking voices (pitch, speed, male vs. female, etc.)

In another follow-up experiment, it was found that subjects typically did notice whenever the pitch, speed, or gender of a speaker was changed while they were listening to simultaneous messages. This implies that listeners can pick out a message from a person based on differences in their voice.

Differences in accents

Differences in accents, however, were not noticed.

In fact, in an experiment with bilingual English/German speakers as the subjects, those subjects did not notice when the language of one of the two conflicting messages they were listening to suddenly changed to German! In another experiment, most subjects did not notice when the message they weren’t focusing on was suddenly reversed, and those who did notice said it sounded “a little quirky.” So changes in dialect, accent, language, etc., do not appear to be the most noticeable to our brains when listening to a voice.

How Does the Cocktail Party Effect Work?

From these studies, we know that, in general, the most important thing for humans (or smart devices) listening to a particular speaker at a loud cocktail party is the listener’s ability to predict the words they didn’t hear, followed by the general sound of their speaker’s voice.

Further research went on to find that the human brain uses many factors to listen to a speaker, including:

- Spatial Continuity. Although speakers failed to tell two messages apart in the directional voice experiment I spoke about earlier (the one with one message in the left ear and another message in the right ear), future studies found that this is overcome when in an environment crowded with more than just two conflicting messages. Humans can focus on a message better when the speaker is staying in the same place in space relative to that listener.

- Loudness. Studies found that someone speaking louder than the surrounding noise is easier to pick out of the crowd and listen to.

- Continuity. When someone is speaking, their sentence remains continuous. Things like their frequency, intensity, and spatial origin remain constant while talking. Your brain is good at focusing on those constants to make sure you keep listening to the same person while ignoring the background noise.

- Visual Channel Effects. Our brains automatically connect sounds to speakers. Imagine watching a movie in a theatre. The speakers emanating the sound may be behind you, but your eyes see the person speaking before you on the screen. Your brain automatically decides to assume the person you see on the screen in front of you is the one talking, so you ‘hear’ the sound coming from the mouth of the person on screen - even when your ears are receiving the sound from behind your head.

These reasons and many others have been found to all combine in our brains so that we can focus on the person speaking - and thus overcome distracting noise in the background that we are also hearing. This amazing skill of various techniques going on in our brains is the essence of how we overcome the cocktail party problem.

Written by: Nick Pellegrino

Sources

"A Review of The Cocktail Party Effect Barry Arons ... - MIT Media Lab." https://www.media.mit.edu/speech/old/papers/1992/arons_AVIOSJ92_cocktail_party_effect.pdf. Accessed 16 May. 2019.