David Dunning is an experimental social psychologist, professor, and author. He is most widely cited for his work on the psychological factors underlying errors in self-evaluation. He has also conducted research in the areas of decision-making, social judgment, motivated reasoning, stereotypes, behavioral economics, trust, and eyewitness testimony.

David Dunning's Childhood

David Alan Dunning was born in 1960 and was raised in Midland, Michigan. As a young boy, Dunning was very energetic and active. At 12 years of age, he and a friend were “roughed up” by guards after they ventured too close to the home of Alden B. Dow, a renowned American architect who was based in Midland.

As a child, Dunning’s dream was to become a cartoonist and later, a screenwriter. At age 13, he submitted a script to Larry Gelbart, producer of the TV show “MASH.” Later, while attending Midland High School, Dunning approached Gene Roddenberry—the creator of the original Star Trek television series—and told him that he wanted to become a screenwriter. Roddenberry encouraged Dunning to “write 1,000 words a day, everyday” if he wanted to become a good writer. Dunning was also a big fan of Buck Henry, a former American actor, screenwriter, and director.

Dunning was very athletic during his youth and claims to have spent much of his early life “running up and down the left side of the [soccer] pitch.” He also developed a love of music from an early age and says the first three albums he bought with his own money were Songs in the Key of Life (by Stevie Wonder), Hotel California (by the Eagles) and Aja (by American rock duo Steely Dan). Dunning became a big fan of Steely Dan and still recalls when one of their concerts was held outside his hometown in 1977.

Educational Background

Dunning obtained his B.A. in Psychology from Michigan State University in 1982 and his Ph.D in Psychology from Stanford University in 1986. He revealed that Michigan State taught him the importance of scientific rigor, while Stanford taught him the importance of incorporating humanity into his work.

Dunning had several mentors during his academic career, including Joel Aronoff and Larry Messe of Michigan State, and Lee Ross and Phoebe Ellsworth of Stanford. Dunning was also greatly influenced by the work of Amos Tversky, a former psychology professor at Stanford. He developed great respect for Tversky, and regarded him as a real-life example of “what smart looks like.” Dunning describes himself as a “researcher in the tradition of Amos Tversky and Daniel Khaneman,” both of whom did significant work on the psychology of human judgment and decision-making.

Dunning is currently a professor of psychology at the University of Michigan and professor emeritus of psychology at Cornell University. He has served as a visiting scholar at the University of Mannheim and the University of Cologne in Germany, as well as at Yale University.

What is the Dunning-Kruger Effect?

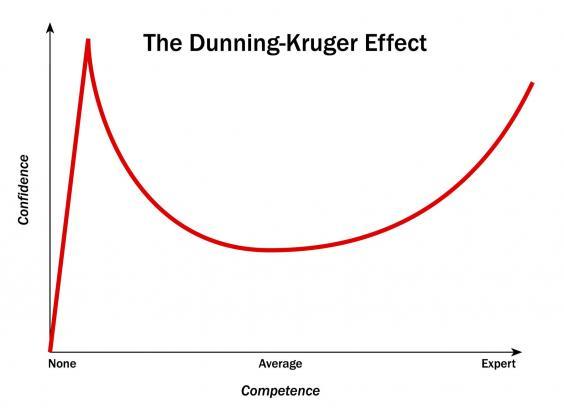

The Dunning-Kruger effect is the name given to a cognitive bias in which people who perform poorly on a task overestimate their performance and abilities. That is, they consider themselves to be more knowledgeable, skillful or competent than they really are. The phenomenon is named after David Dunning and fellow psychologist, Justin Kruger, both of whom documented the effect in a series of studies conducted at Cornell University in 1999.

In those studies, undergraduate psychology students were given tests designed to assess: (1) their ability to spot humor, (2) logical reasoning ability, and (3) grammar. They were then asked to rate how well they thought they had done on a percentile scale. The results? Students with the lowest scores grossly overestimated their abilities. For example, those who scored in the 12th percentile on one test rated themselves in the 62nd percentile. Although they had scored in the bottom quarter of the distribution, they believed their performance was above average.

Why Does It Occur?

According to Dunning and Kruger, the lack of awareness among low scorers occured because the skills needed to perform well on a task are the same skills needed to evaluate how well that task had been performed. Put another way, if people lack the skills needed to answer a set of questions correctly, they also lack the skills needed to judge whether their or someone else’s answers are correct. Low ability not only limits people’s performance on a task; it also deprives them of the insight needed to accurately evaluate their performance. In the words of the researchers, it deprives them of the ‘metacognitive skills’ needed to accurately evaluate their competence. (Metacognitive skills allow us to evaluate ourselves—to step back and think about our thoughts and other cognitive processes).

Who Does It Affect?

The Dunning-Kruger effect has been shown to be quite robust across several studies. It has been demonstrated among:

- undergraduate students sitting an exam

- medical students tasked with conducting interviews

- medical laboratory technicians asked to evaluate their level of skill on the job

- aviation students taking a pilot knowledge test

- college students involved in a debate tournament

All humans are at risk of falling into the Dunning-Kruger trap since we all have areas in which we are incompetent. As such, we do not need to look far to find examples of the effect in everyday life. All of us have seen and heard people singing quite poorly, yet confidently, at local karaoke bars, on websites such as Youtube, and even on popular talent shows like America’s Got Talent. To a neutral observer or judge, their performance might be absolutely horrendous, but in their own estimation, they are nothing short of amazing.

As counterintuitive as it may seem, the Dunning-Kruger effect shows that in many cases, the less people know about something, the more they think their knowledge is adequate or even superior. Who of us has not had the unfortunate experience of speaking with someone who knows very little about a subject but believes he or she knows everything there is to know about it? It is just as Charles Darwin famously said, “Ignorance more frequently begets confidence than does knowledge.”

When Does It Occur?

The findings of Dunning and Kruger’s study should not be taken to mean that people who are incompetent in a given domain always overestimate their competence in that domain. Several other factors influence how likely they are to overestimate their performance, one of which is the actual domain in question. For example, people may have a tendency to overestimate their knowledge of politics or history, but very few would be under the illusion that they are as fast as Usain Bolt.

In areas such as politics and history, competence is based on knowledge—a competent historian is one who knows a great deal about history. In such areas, it is easy for people to overestimate their competence since the knowledge needed to be a good historian is the same knowledge needed to judge how good of a historian one is. An incompetent historian would lack the knowledge needed to properly evaluate his (or someone else’s) performance, setting the stage for the Dunning-Kruger effect to occur. In domains such as athletics where competence depends not just on knowledge but on actual physical skill, people are much less likely to develop a false sense of expertise.

For the Dunning-Kruger effect to occur, the researchers also noted that individuals must “satisfy a minimum threshold of knowledge, theory or expertise that suggests to themselves that they can generate correct answers.” The reason for this is clear. Hardly anyone (if anyone at all) would overestimate their ability to translate an article into Arabic when they have zero knowledge of that language. In other areas where individuals possess some knowledge, however, there is a basis for overestimating their abilities.

How Can It Be Overcome?

Dunning and Kruger found that people’s tendency to overestimate their performance can be overcome by increasing their competence. In one of their studies, when low performers on a test of logic received training in logical reasoning, they became better at evaluating their previous performance. The more people learn about a particular subject, the more they are able to recognize gaps in their knowledge and ability, and the more realistic their self-evaluations become.

Aside from seeking to increase one’s level of competence, Dunning offers several other practical suggestions for avoiding or minimizing the Dunning-Kruger effect. He encourages individuals to:

- Seek feedback on their performance from trusted individuals

- Be mindful of when the effect is most likely to occur, for example, when learning something new

- Avoid making quick, impulsive decisions

- Take the time to consider ways in which they could be wrong or could be overlooking important information when making decisions

What About Top Performers?

In Dunning and Kruger’s original study, the top performers had more accurate estimations of their performance than low performers. However, they tended to underestimate how well they had done. For example, although they achieved scores in the 89th percentile on one test, they rated themselves in the 70th percentile. The issue, according to Dunning and Kruger, is not that they believe they are less competent than they really are; they simply believe that other people are also very knowledgeable about the subject.

Other Research Interests

In addition to his above-mentioned work, Dunning has also conducted research in several other areas, including:

Social judgment - In a study conducted with Andrew F. Hayes, Dunning set out to evaluate the role of the self in people’s judgments of others. The results of the study suggest that people activate information about themselves and use their own behavior as a reference point when judging the traits and abilities of others. Dunning demonstrated these ‘egocentric comparisons’ in a series of studies conducted with some of his colleagues at Cornell University.

In one of those studies, participants were asked to describe the characteristics of an effective leader. Interestingly, the descriptions they gave were often reflections of themselves. Participants who were people-oriented placed an emphasis on social skills, while goal-oriented participants stressed task skills.

Motivated Reasoning - Motivated reasoning refers to thought that is aimed at supporting a favored or predetermined conclusion. Dunning’s interest in the subject relates primarily to how motivated reasoning influences thoughts about the self. As he notes in his writing, people are generally motivated to think well of themselves and to be optimistic about their futures. As a result, they actively distort, ignore, or accentuate existing evidence in order to reach pleasant conclusions about the self, as opposed to threatening ones.

In a series of studies with Emily Balcetis, Dunning found that motivated reasoning not only affects conscious thought, but also affects preconscious perceptual experience, such as vision. In one study, when participants were presented with ambiguous images that could be interpreted in one of two ways (e.g., as either a B or the number 13), they tended to see the image in the way that would result in more favorable outcomes for them.

Eyewitness testimony - Dunning’s work in this area involves identifying factors that can help distinguish between accurate and inaccurate eyewitness accounts. In a study conducted with Lisa Beth Stern, he focused on one particular aspect of eyewitness testimony, namely the identification of a perpetrator from a lineup. The researchers found that accurate witnesses could be distinguished from those who made inaccurate identifications by simply asking them about the decision-making processes that led to their judgments.

Accurate witnesses had a hard time explaining exactly how they had arrived at their decision; their recognition of the perpetrator was automatic (e.g., “I don't know why, I just recognized him,” or “His face just “popped out at me.”) In contrast, inaccurate witnesses provided much longer explanations based on a process of elimination (e.g., “I compared the photos to each other in order to narrow the choices.”) Accurate witnesses also arrived at their decisions more quickly than witnesses who were inaccurate.

Applications of Dunning’s Theories

The Dunning-Kruger effect has been used to explain people’s behavior in several domains, including education, politics, healthcare, and business. Knowing the conditions under which the effect is likely to occur, and being able to identify it when it does occur, can help individuals to lessen its impact.

In education, for example, teachers sometimes rely on students’ evaluation of their own competence to determine the direction of lessons. If students claim to understand a particular topic, the teacher might promptly move on to the next topic for discussion. However, the Dunning-Kruger effect suggests that this might not be the best approach since students who have not mastered the lesson might overestimate their level of competence. A more objective means of assessing competence would therefore be more suitable.

In the workplace, employees are often asked to complete self-evaluations which may influence their eligibility for promotions and other benefits. In light of the Dunning-Kruger effect, managers would need to exercise caution when interpreting scores on these measures since less competent workers may overestimate their skills and abilities, while the most competent workers may underestimate theirs. It would be wise for employers to exercise similar caution when selecting job candidates based on their performance in interviews. The most confident candidates could actually be the least qualified for the job.

In both educational and work settings, the Dunning-Kruger effect also helps to explain why poor performers are often resistant to constructive feedback. Their lack of competence robs them of the skills needed to accurately assess their own performance, so they naturally conclude that the feedback is not justified. For example, a student with limited writing skills may complain about receiving an ‘F’ for an essay he believes is well-written but that is actually riddled with grammatical errors. Simply pointing out the errors might not be enough to make the student more accepting of the grade. The Dunning-Kruger effect suggests that in such a situation, additional training would be beneficial. As the student’s knowledge of grammar improves, so would his ability to evaluate his own writing. He would then be able to see for himself why his original grade was merited. The same principle can be applied in the workplace.

Criticisms of Dunning’s Theories

According to Dunning and Kruger, incompetent people overestimate their performance and abilities because they lack the metacognitive skills needed to know that they are incompetent. Other theorists, however, have proposed alternative explanations for the original results. Two of the most common explanations are:

- Regression to the mean - Many critics contend that the Dunning-Kruger effect is merely a statistical phenomenon, a prime example of regression to the mean. Given that participants’ actual test scores are imperfectly correlated with estimates of their performance, participants who obtain extreme scores on one variable will tend to have less extreme scores on the other variable. Low scorers will therefore tend to rate themselves as more competent than their test scores suggest, while high scorers will tend to rate themselves as less competent.

- Self-enhancement motives - Proponents of this explanation claim that most people have a tendency to view themselves in an overly positive light. This is sometimes referred to as the ‘better-than-average heuristic’ and is believed by some to account for people’s inflated perceptions of their performance and abilities.

In Dunning and Kruger’s original study, low scorers were the worst at estimating their performance, while top scorers were the most accurate. As previously explained, the researchers suggested that this pattern resulted from differences in metacognitive ability. However, other researchers have challenged this assumption. For example, Katherine A. Burson and her colleagues found that the difference in the accuracy of estimates between high and low scorers actually decreases, and even reverses, according to task difficulty.

In one study where students were asked fairly difficult questions about their university, the top scorers were just as inaccurate in estimating their performance as were the low scorers. In a subsequent study, when participants were given very difficult tasks, the low performers actually proved to be better at estimating their performance than the top performers.

According to the researchers, when given fairly easy tasks (such as those in the original Dunning and Kruger study), most people assume they are pretty good compared to others. This explains why in the original study, low scorers significantly overestimated their performance, while top performers seemed to be more accurate. When the task is difficult, however, people tend to assume they performed poorly compared to others. Hence, in studies by Burson and her colleagues, low scorers seemed better at judging their performance while high scorers seemed worse.

According to the researchers, these results show that people of low and high ability do not really differ in their ability to evaluate their performance as Dunning and Kruger suggest. Both groups have similar difficulty estimating how their performance compares to that of others. Whether high or low performers are better judges of their performance therefore depends more on task difficulty than on metacognitive skills.

David Dunning's Books, Awards, and Accomplishments

Dunning has published over 100 scholarly articles, book chapters, reviews and commentaries. He is the author of the book Self-Insight: Roadblocks and Detours on the Path to Knowing Thyself (2005), editor of the book Social Motivation (2011), and co-editor of The Self in Social Judgment (2005).

Dunning was a fellow of the American Psychological Society and the American Psychological Association. He also served as an associate editor of the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Dunning was appointed as an Executive Officer for two organizations: the Society for Personality and Social Psychology and the Foundation for Personality and Social Psychology.

Personal Life

Dunning follows politics in the United States very closely and is a big fan of movies and music. His favorite movie is The Insider, starring Al Pacino and Russell Crowe. He also enjoys watching “intellectual fantasy series like Watchmen and Westworld.” These days, his music interests are centered on Canadian and British pop music.

Dunning plays golf in his spare time but as he has become less physically active with age, he satisfies his passion for sports primarily by watching games on the television. He watches popular soccer tournaments such as the World Cup and the English Premier League regularly and is a passionate supporter of English soccer club Arsenal.

References

David Dunning. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://behavioralpolicy.org/people/david-dunning/

Duignan, B. (2019). Dunning-Kruger effect. In Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/science/Dunning-Kruger-effect#ref1272035

Dunning, D., & Hayes, A. F. (1996). Evidence for egocentric comparison in social judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(2), 213-229.

Dunning, D., & McElwee, R. O. (1995). Idiosyncratic trait definitions: Implications for self-description and social judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(5), 936-946.

Dunning, D., Perie, M., & Story, A. L. (1991). Self-serving prototypes of social categories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(6), 957-968.

Dunning, D., & Stern, L. B. (1994). Distinguishing accurate from inaccurate eyewitness identifications via inquiries about decision processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(5), 818-835.

Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (2009). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Psychology, 1, 30-46.

Patel, T. (2020). Confidence and its impact on your aspiring career. In M. M. Shoja et al.(Eds.), A guide to the scientific career: Virtues, communication, research, and academic writing. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Ritholtz, B. (2010). Transcript: David Dunning. Retrieved from https://ritholtz.com/2020/03/transcript-david-dunning/

Yarkoni, T. (2010). What the Dunning-Kruger effect is and isn't. Retrieved from https://www.talyarkoni.org/blog/2010/07/07/what-the-dunning-kruger-effect-is-and-isnt/