In the late 20th century, a psychologist named Howard Gardner believed that the way people thought about intelligence was too narrow and that was more helpful to recognize other mental strengths individuals may have. What he proposed has made him one of the most well-known psychologists living today.

Who Was Howard Gardner?

Howard Gardner is an American psychologist who specializes in cognitive and developmental psychology. He is best known for his theory of multiple intelligences. His theory has helped many professionals in the field of education to embrace the idea that there are many ways to be intelligent.

Howard Gardner's Birth

Howard Earl Gardner was born on July 11, 1943 in Scranton, Pennsylvania. His parents were Ralph and Hilde Gardner. Gardner’s parents were German-Jewish immigrants who fled from Nazi persecution in Germany. They arrived in the United States with their three year old son, Eric, on November 9, 1938, just before the outbreak of World War II.

Howard Gardner's Family Life

Ralph and Hilde Gardner moved to Scranton soon after they landed in America. At the time, Scranton was a small coal-mining town. Ralph Gardner and a few associates “traced the fate of every family member in Europe or elsewhere in the Diaspora” in an attempt to provide aid during and after the Holocaust. It was not uncommon for family members to spend many nights at their small residence in Scranton.

Four years after the Gardner family settled in Scranton, Hilde watched as Eric died in a tragic sledding accident. Eric did not speak any English when he first arrived, but he demonstrated ability beyond his years and did very well in school. Gardner’s parents were overcome with grief and felt as if they lost everything. Many years later, Gardner’s parents told him they may have considered suicide if Hilde was not pregnant with him at the time Eric died.

After Howard Gardner was born in 1943, his parents had a daughter named Marion three years later. According to Gardner, the Holocaust and the death of his older brother Eric “cast large shadows” on his childhood. Gardner’s parents did not speak about what happened during the Nazi regime to him, his sister, or to acquaintances. And they did not tell him about his older brother Eric either. He believes they were unable to. When Gardner asked about the little boy in all the pictures around the house, his parents told him that it was a child from the neighborhood. Gardner eventually uncovered the truth when he was ten years old after he found clippings about Eric’s death.

Howard Gardner's Childhood

Gardner describes his childhood self as “a dark-haired, slightly chubby, bespectacled boy of above average height, who walked and moved somewhat awkwardly.” He was born with crossed eyes and had poor eyesight, but he also had a very curious mind and loved to read and write. Gardner would often ask his parents, teachers, adults, and older children very difficult questions. When he was seven years old he considered himself a journalist and began publishing his own home and school newspapers.

Gardner was also a talented piano player and may have pursued a career in music. However, he stopped playing as a teenager because he thought it was too troublesome to practice. Gardner’s parents discouraged him from getting involved in athletics or risky physical activities due to the circumstances of Eric’s death. He spent several years as a Cub Scout and Boy Scout, reaching the rank of Eagle Scout at the age of thirteen.

Although Gardner eventually had a successful career as a psychologist and scientist, as a boy he was not particularly fond of exploring the outdoors. He was not interested in studying insects or dissecting mice unless he was trying to earn a scouting merit badge. His youth was not spent taking cars or gadgets apart and putting them back together. His only exposure to psychology occurred during his teenage years when he read an interesting discussion on color blindness in a psychology textbook.

Nevertheless, education was of great importance in the Gardner household. Gardner’s parents wanted him to attend Phillips Academy Andover, but he chose to go to Wyoming Seminary because it was closer to home. He was an excellent student who did very well in math and science, but his main interests were in literature, history, and the arts. He believes his parents had a major impact on his development, especially after they transferred their aspirations to him following the death of his talented older brother.

Educational Background

Gardner enrolled at Harvard College in September 1961. When he first arrived, he was a bit intimidated by the fact he now had peers who could match him in academics and the arts. However, he soon regained his focus and took advantage of the wide variety of academic courses available to him.

Gardner’s initial objective at Harvard was to major in history. In his junior and senior years, he was tutored by psychoanalyst Erik Erikson. Over time, Gardner’s interest in the social sciences grew as he studied under cognitive psychologist Jerome Bruner and sociologist David Riesman. Interestingly, he also took a number of pre-med and pre-law courses to prove to himself and his parents that he could have had a successful career in those fields had he chosen to stick with them. In 1965, Gardner graduated summa cum laude with a bachelor’s degree in social relations.

After receiving his first degree, Gardner spent a year at the London School of Economics studying philosophy and sociology as a Harvard Fellow. However, he decided to return to Harvard to pursue graduate studies in developmental psychology after being inspired by the works of psychologist Jean Piaget. In 1967, Gardner became a founding member of Project Zero—a research group that studied cognition with a focus on creativity and artistic thought. He earned his PhD in developmental psychology in 1971.

With his doctoral studies complete, Gardner worked with behavioral neurologist Norman Geschwind at Boston Veterans Administration Hospital as a postdoctoral fellow. He conducted neuropsychology research at the hospital for more than 20 years. According to Gardner, he “probably could have had a reasonably successful career as a cognitive neuroscientist, or perhaps even a developmental neurobiologist,” but he eventually “left the straight science track and moved to issues of educational reform and social policy.”

Gardner accepted a teaching position at Harvard Graduate School of Education in 1986. Since 1995, he has spent most of his time working on The GoodWork Project—a program that promotes ethics and excellence in work and life. In 1998, Gardner was selected as the John H. and Elisabeth A. Hobbs Professor of Cognition and Education at Harvard. He retired from teaching at the end of the 2019 academic year.

How Did Howard Gardner Develop His Theory of Multiple Intelligences?

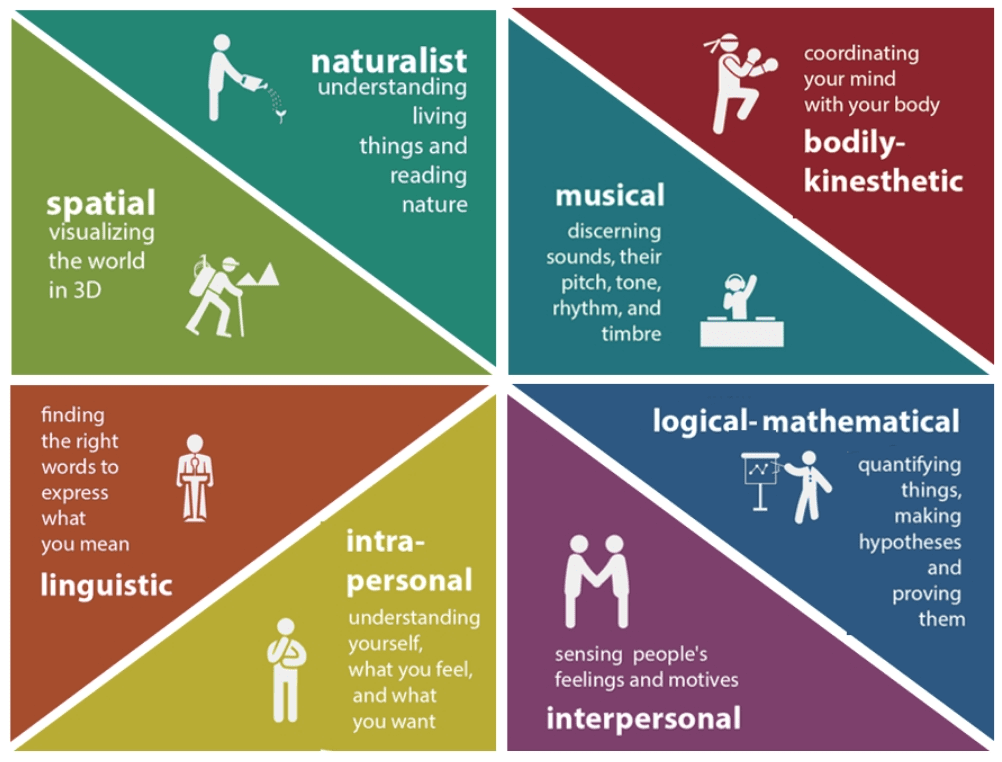

Gardner developed his theory of multiple intelligences (MI theory) in the late 1970’s to early 1980’s. Up to that time, intelligence was generally conceived of as a singular quality influencing performance on all cognitive tasks. Gardner felt that this view of intelligence was too narrow and failed to capture the full range of human intellectual faculties. He argued instead that humans do not possess a unitary intelligence but rather, several different types of intelligence. He proposed eight different forms of intelligence, namely:

- Linguistic - The ability to learn and use languages in oral and written form, for example, through reading, writing, speaking, and listening.

- Logical-mathematical - The ability to engage in logical reasoning, display scientific thought, solve abstract problems, and perform mathematical calculations.

- Spatial - The ability to recognize and manipulate spatial images; involves a propensity for learning visually.

- Musical - The ability to compose, produce, and derive meaning from music and sound patterns.

- Bodily-kinesthetic - The ability to use one’s body skilfully to solve problems, create products, and express oneself.

- Naturalistic - The ability to recognize and differentiate elements of the natural world, including plants, animals, and weather patterns; involves close attention to nature and the ability to understand environmental issues.

- Interpersonal - The ability to discern, understand, and respond appropriately to other people’s moods, desires, intentions, and motivations.

- Intrapersonal - The ability to identify and understand one’s own moods, desires, intentions and motivations.

What Makes This a Theory?

One common question about the Theory of Multiple Intelligences is why it's called a theory. This Reddit post (and its comments) provide the answer!

"I would say that the main distinction between "laws" and "theories" is just that a law is a simple statement, while a theory is something more complicated. Neither of them necessarily explain "why" something happens - for example both Newton's law of universal gravitation and the theory of general relativity are models of gravity, but neither of them really explain why gravity exists, they just state how it works."

About Howard Gardner's Theory of Multiple Intelligences

Gardner did not rule out the possibility that other forms of intelligence exist. He himself later considered adding a ninth form of intelligence known as existential intelligence. This involves the ability to consider life’s big questions, such as those relating to life, death and love. However, existential intelligence was never formally included in MI theory since Gardner was not convinced that it sufficiently met the criteria for identification as a unique intelligence.

The eight intelligences are said to be independent of each other and can function autonomously. However, many tasks require a blend of intelligences. For example, when performing an operation, a surgeon needs both spatial intelligence in order to guide the scalpel to the correct location, as well as bodily-kinesthetic intelligence in order to manipulate the scalpel with dexterity. Similarly, a rousing musical performance requires not just musical intelligence, but also bodily-kinesthetic intelligence. Even a measure of interpersonal intelligence is needed in order for one to successfully engage members of the audience and stir their emotions.

Linguistic and logical-mathematical intelligence are the two types of intelligence traditionally emphasized in formal educational settings. They are also the ones on which conventional tests of intelligence have been based. These tests purport to give an estimate of the test-taker’s general intelligence which can then be used to predict performance on diverse tasks. However, Gardner dismissed the idea of a ‘general’ intelligence, noting that people who perform exceptionally well in one cognitive domain will not necessarily display the same level of aptitude in another.

Another point of departure between MI theory and more traditional theories of intelligence has to do with the origin of intelligence. Many other theories describe intelligence as an inborn capacity that remains fairly constant throughout life. The idea is that one’s intellectual ability is set from birth and there is very little one can do to modify it. By way of contrast, MI theory suggests that intelligence is as much a function of ‘nurture’ as it is ‘nature.’ Even though individuals are born with a certain set of skills and potentials, Gardner suggests that these can be enhanced (or diminished) by environmental factors.

Gardener believed that all humans (except in cases of severe brain damage) possess varying levels of all eight intelligences. It would therefore be incorrect to state that an individual lacks a particular form of intelligence. Gardner believed that we all have unique patterns of cognitive strengths and weaknesses, with no two individuals displaying the same profile of abilities.

In recent years, Gardner suggested two broad types of intelligence profiles: searchlight and laser-like. These profiles describe the relative strengths of intelligences within an individual. People with searchlight profiles readily shift among intelligences that tend to be comparable in strength. Those with laser-like profiles have one or two intelligences that are more dominant than the others and are used in greater depth. Gardner believes the searchlight profile is typical of politicians and businessmen, while the laser-like profile is characteristic of artists, scholars and scientists.

The Goodwork Project

Since the mid 1990’s, much of Gardner’s attention has been focused on The Goodwork Project (recently renamed The Good Project), which began as a collaboration between himself and two of his colleagues, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi and William Damon. The purpose of the project is to determine the factors that enable people to carry out “good work” in their chosen disciplines and to increase the incidence of such work throughout society.

“Good work” is a term used to describe work that reflects the three Es: (1) Excellence - work that is high in quality, (2) Ethics - work that is socially and morally responsible, and (3) Engagement - work that is meaningful and beneficial to the worker. Having interviewed hundreds of professionals across several disciplines, the researchers identified several variables associated with “good work,” including:

- Positive early experiences within the family

- Religious and spiritual values

- Collaboration with peers and colleagues

- Support and inspiration from authority figures and mentors

Gardner and his colleagues make no attempt to offer a specific formula for “good work.” However, they believe that if workers routinely consider and seek powerful answers to four specific questions, they will be well on their way to producing “good work.” The four questions (or four Ms) are:

- What is the Mission of our field?

- What are the positive and negative Models that we need to keep in mind?

- When we look into the Mirror as individual professionals, are we proud or embarrassed by what we see?

- When we hold up the Mirror to our profession, are we proud or embarrassed by what we see?

Applications of Gardner’s Theory

Gardner’s MI theory has been applied primarily in educational circles. Hundreds of schools across many countries have used the core principles of the theory to revise their mission, curriculum, and approach to teaching and assessment. Some of the educational interventions derived from his theory include:

- Individualizing students’ instruction by becoming familiar with their strengths, weaknesses and interests.

- Presenting lessons in a variety of non-traditional ways, for example, through art, music, field trips, games, multimedia presentations, and role-playing.

- Employing a variety of non-traditional assessment methods, including portfolios, projects, videos and other creative or performance-based tasks.

- Establishing learning centers in the classroom, each dedicated to a different form of intelligence. Students can move through the centers, exploring the topic being taught in different ways.

- Team teaching in which teachers focus on their own intellectual strengths, allowing students to be exposed to a variety of instructional methods.

- Cooperative learning teams in which students are grouped either (a) homogeneously, according to a shared intellectual strength, or (b) heterogeneously, according to varying intellectual strengths. Homogenous groups allow learners to challenge one another in their areas of strength, while heterogeneous groups allow them to learn from one another and develop their weaker abilities.

MI theory has also been applied in occupational spheres, particularly in the areas of hiring, job placement, and team assembly. Multiple intelligence evaluations can assist HR managers and CEOs to better align the skills and abilities of potential candidates with the functions associated with each role.

MI theory may also be used during career counseling to help students understand the range of careers typically associated with their intellectual profile. In this way, students are able to make more informed vocational decisions and are in a better position to choose careers that best suit their interests and abilities.

Criticisms of Gardner’s Theory

A popular criticism of MI theory is that it was not developed on the basis of empirical research. This critique stems from the fact that Gardner himself did not undertake any form of psychometric testing or empirical study to support his classification system or test his theory. Instead, he relied on existing research findings across various disciplines, including neuroscience, anthropology, evolutionary biology, and psychology. In Gardner’s view, this multi-disciplinary synthesis of research findings provides a sufficient empirical framework for the theory, despite the fact that it has not been subjected to in-depth experimental investigation.

As it relates to the number of intelligences identified, Gardner’s critics fall into one of two camps. On one hand, there are critics who claim that MI theory expands the concept of intelligence to such an extent that it is no longer a useful construct. On the other hand, some argue that the eight intelligences are not specific enough and need to be further expanded. Gardner acknowledged the latter argument, suggesting the possibility that there may be sub-intelligences within each of the eight abilities he specified. However, in Gardner’s view, any attempt to list all of these sub-intelligences would render the theory too complex and unwieldy, making application more difficult.

Other critics have argued that:

- Multiple Intellignece theory fails to explain how the various intelligences interact with one another.

- Gardner’s criteria for identifying unique intelligences is arbitrary and subjective.

- What Gardner calls intelligences are simply talents, cognitive styles, or personality traits.

Howard Gardner's Books, Awards, and Accomplishments

Howard Gardner has authored and co-authored thirty books which have been translated into several languages. Some of his literary works include:

- Intelligence: Multiple Perspectives, 1995

- Practical Intelligence for School, 1997

- The Disciplined Mind: Beyond Facts and Standardized Tests, the K-12 Education that Every Child Deserves, 2000

- Intelligence Reframed: Multiple Intelligences for the 21st Century, 2000

- Development and Education of the Mind, 2005

- Making Good: How Young People Cope with Moral Dilemmas at Work, 2005

- Changing Minds, 2006

- Multiple Intelligences: New Horizons in Theory and Practice, 2006

- Responsibility at Work: How Leading Professionals Act (or Don't Act) Responsibly, 2007

- Extraordinary Minds: Portraits of Four Exceptional Individuals and an Examination of Our Own Extraordinariness, 2008

- Good Work: When Excellence and Ethics Meet, 2008

- Five Minds for the Future, 2009

- GoodWork: Theory and Practice, 2010

- Leading Minds: An Anatomy of Leadership, 2011

- The Unschooled Mind: How Children Think and How Schools Should Teach, 2011

- Creating Minds: An Anatomy of Creativity Seen Through the Lives of Freud, Einstein, Picasso, Stravinsky, Eliot, Graham, and Ghandi, 2011

- Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences, 2011

- Truth, Beauty, and Goodness Reframed: Educating for the Virtues in the Age of Truthiness and Twitter, 2012

- The App Generation: How Today’s Youth Navigate Identity, Intimacy, and Imagination in a Digital World, 2013

- Mind, Work, and Life: A Festschrift on the Occasion of Howard Gardner’s 70th Birthday, 2014

Gardner has also received 31 honorary degrees from universities around the world. A few of his other awards include:

- MacArthur Prize Fellowship, 1981

- Book Award, The National Psychology Awards for Excellence in the Media, 1985

- William James Book Award, American Psychological Association, 1987

- University of Louisville Grawemeyer Award in Education, 1990

- John S. Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship, 2000

- Prince of Asturias Award in Social Sciences, 2011

- Awarded the Brock International Prize in Education, 2015

Gardner is a member of the American Philosophical Society, the National Academy of Education, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce. He is also a board member at the American Philosophical Society and the New York Museum of Modern Art.

Is Howard Gardner Married?

Howard Gardner married his first wife, Judy Krieger, in 1966. Like Gardner, she was a graduate student in psychology at the time of their marriage. For their honeymoon they went to Geneva to meet renowned Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget. The couple had three children together—Kerith, Jay, and Andrew—before they went through a difficult divorce years later.

In 1973, Gardner met his second wife, Ellen Winner. Winner was eager to pursue graduate studies in clinical psychology after majoring in literature and studying painting at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. However, a job opening at Harvard as a research assistant in the psychology of art caught her attention. Winner committed to the job for two years but she would remain with Gardner long after. They were married in 1982. The couple adopted a child from Taiwan named Benjamin in 1986.

Is Howard Gardner Alive Today?

Yes! Today, Kerith oversees the National Academy of Education, Jay works as a photographer, and Andrew is a teacher. Gardner also has five grandchildren—Oscar, Agnes, Olivia, Faye Marguerite, and August Pierre.

References

Biography of Howard Gardner. (n.d.). Howard Gardner. Retrieved from https://howardgardner.com/biography/

Davis, K., Chistodoulou, J., Seider, S., & Gardner, H. (2011). The theory of multiple intelligences. In R. J. Sternberg & S. B.Kaufman (Eds.), Cambridge handbook of intelligence (pp.485-503). UK: Cambridge University Press.

Encyclopedia Britannica. (n.d.). Howard Gardner. In Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Howard-Gardner

Gardner, H. (n.d.). One way of making a social scientist. Retrieved from https://howardgardner01.files.wordpress.com/2012/06/one-way-of-making-a-social-scientist2.pdf

Gardner, H. & Winner, E. (2006, November 1). On being a couple in psychology. Retrieved from https://www.psychologicalscience.org/observer/on-being-a-couple-in-psychology

Goodwork Project. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://coa.stanford.edu/research/goodwork-project

Howard Gardner: Factfile. (2001, May 22). The Irish Times. Retrieved from https://www.irishtimes.com/news/education/howard-gardner-factfile-1.309216

McInerney, D. M. (2014). Educational psychology: Constructing learning (6th ed.). Australia: Pearson.

Mineo, L. (2018, May 9). The greatest gift you can have is a good education, one that isn’t strictly professional. The Harvard Gazette. Retrieved from https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2018/05/harvard-scholar-howard-gardner-reflects-on-his-life-and-work/

Verducci, S., & Gardner, H. (2005). Good work: Its nature, its nurture. In F. A. Huppert, N. Baylis, & B. Keverne (Eds.), The science of well-being (pp.343-359). New York: Oxford University Press.