Jerome Bruner was an American psychologist, researcher, and educator. He made key contributions in a number of areas, including memory, learning, perception, and cognition. Bruner spearheaded the “cognitive revolution” and his work led to significant changes in the American school system. The American Psychological Association (APA) ranks Bruner as the 28th most eminent psychologist of the 20th century.

Jerome Bruner's Childhood

Jerome Seymour Bruner was born on October 1, 1915 in New York City. His parents, Herman Bruner and Rose Gluckman Bruner, were Jewish immigrants from Poland. Jerome was the youngest of three children in the family. His older sisters were Min and Alice. He also had an older half brother named Adolf.

Bruner was born blind because of cataracts. When he was two years old, he had an experimental operation to remove the cataracts and this restored his vision. However, his poor eyesight meant he had to wear thick eyeglasses throughout his life. Although Bruner did not have vivid memories of being blind, he believed the experience may have affected his attachment to his parents.

Bruner’s father worked as a watch manufacturer and operated a watchmaking company. His mother was a homemaker and focused on raising the children. Bruner was raised on the southern shore of Long Island and enjoyed spending time by the sea. He had a couple of close friends, with whom he sometimes went rowing or sailing. Bruner described himself as “quite a shy, geeky boy,” who was very different from his confident, outgoing older sister Alice.

When Bruner was 12 years old, his father Herman died from liver cancer. Although Herman sold the watchmaking company to Bulova before he died and left the family with money, the loss was severely felt. Bruner’s mother, Rose, was deeply affected and never really got over it.

Shortly after her husband died, Rose moved the family from Long Island to Florida. However, it took a while for them to get settled. Bruner and his siblings moved every year as Rose, likely overwhelmed with grief, went through a period of wandering. As a result, Bruner attended a series of high schools as a teenager.

Bruner believed that the communication within his family changed after his father died. His family members were no longer as intimate as they were before. The communication issues increased when Alice got married young and left to start her own family. These experiences may have influenced Bruner to become a more self-sufficient and rebellious person later in life.

Educational Background

After Bruner graduated from high school, he enrolled at Duke University. While at Duke, he was taught by William McDougall—a renowned British psychologist. McDougall was known to be an opposer of behaviorism (the dominant school of thought at the time) and encouraged Bruner to think beyond “stimulus and response.” Bruner earned his bachelor’s degree in psychology and graduated from Duke in 1937.

When Bruner decided to leave Duke to further his studies, McDougall encouraged him to go anywhere except Harvard. So Bruner, a rebel at heart, immediately registered at Harvard University. Some of his professors at Harvard included Henry Murray, Gordon Allport, Smitty Stevens, and Edwin Boring. Bruner earned his master’s degree in psychology in 1939 and his PhD in psychology in 1941.

Shortly after receiving his doctoral degree, Bruner tried to join the United States military. He wanted to fight in World War II, but his application was rejected because of his poor eyesight. Instead, he was drafted into the Office for Strategic Studies (OSS)—a US military intelligence agency. Bruner was a part of the OSS staff that worked with members of the US Office of War Information (OWI) and the British Political Warfare Executive (PWE) to form the Psychological Warfare Division (PWD) of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force. Bruner’s assignments included working with wartime propaganda, studying foreign radio broadcasts and following the invasion force to France to investigate which liberated French villages could be trusted.

When World War II ended in 1945, Bruner returned to Harvard as a faculty member. For most of the late 1940s, he and Leo Postman conducted research on how needs, motivations, and expectations affect perception. Bruner also became more involved in cognitive psychology and specifically, the cognitive development of children. He eventually became a professor of psychology at Harvard in 1952.

Bruner’s interest in the US school system grew in the late 1950s. After attending a ten day meeting of scholars and educators in 1959, he published the landmark book The Process of Education in 1960. This book sparked many educational programs and experiments during the 1960s. Bruner was asked to join a number of committees and panels, including the President’s Advisory Panel of Education for both the Kennedy and Johnson administrations.

In 1960, Bruner co-founded the Harvard Center for Cognitive Studies. His research focused on cognition and helped to end the dominance of behaviorism in psychological research in America. He also served as the president of the American Psychological Association (APA) in 1965.

Bruner left Harvard in 1972 to teach at Oxford University in England. To get to England, he sailed his boat across the Atlantic Ocean. While at Oxford, he conducted research on children’s language. Bruner returned to the United States in 1980 when he accepted a position at The New School in New York City. He joined the staff at New York University in 1991 where he taught primarily at the NYU School of Law.

Bruner’s Three Modes of Representation

Bruner’s theory of cognitive development deals with how knowledge is stored or represented in memory. He proposed three modes of representation, the first of which develops in infancy with the other two gradually emerging later. Although these ways of thinking evolve in stage-like progression, we do not abandon them as we move from one phase of development to another. All three modes of representation are interconnected and utilized in adulthood. The three modes are as follows:

Enactive (0-1 yr) - In their first year of life, babies learn primarily by doing. As they interact with their environment through physical actions such as tasting, touching, moving and grasping, enactive representations are formed. Knowledge is stored as a series of motor responses or what we commonly refer to as ‘muscle memory.’ For example, infants may store the movements involved in shaking a rattle or holding a bottle. When the memory is retrieved, the movement is recreated. Adults also make use of this form of representation when they engage in motor tasks such as riding a bicycle, driving, typing, or playing a musical instrument.

Iconic (1-7 yrs) - As children get older, they develop the ability to store knowledge in the form of mental images or icons. These images may be based on visual, auditory or other sensory inputs. When we use pictures, maps, diagrams and videos to aid learning, we are making use of the iconic mode.

Symbolic (7 yrs onwards) - This is the last mode of representation to develop. It involves storing information in the form of abstract symbols rather than images. Two of the most commonly used symbols are words and numbers. The symbolic mode allows for information to be summarized and more easily manipulated. Greater flexibility and complexity of thought therefore become possible. Most adult thought is stored in the symbolic mode.

Discovery Learning

Not only did Bruner theorize about cognitive development, he also wrote extensively about the process of learning. He strongly believed that children should be active participants in the learning process, rather than passive recipients of knowledge. He promoted the idea of discovery learning in which children learn through engagement, experimentation, and exploration.

From Bruner’s standpoint, the objective of instruction should be to help learners become self-sufficient in problem solving. Rather than transmitting pre-packaged facts and explanations, teachers should function as facilitators, helping students to discover principles for themselves. This means that teachers would give learners access to necessary information without organizing it for them. The students would sort the information for themselves, discovering in the process the relationships between different concepts and ideas.

A teacher interested in applying these principles might present pupils with a puzzling situation or interesting question, such as: ‘Why does the flame go out when a burning candle is covered by a glass jar?’ Instead of giving students the answer, the teacher might present them with materials they can use to investigate the problem on their own. Learners become like little scientists, making observations, suggesting hypotheses based on previous knowledge and then testing them.

Bruner’s approach to learning has been called a constructivist approach since it involves the learner actively constructing new ideas based on past and current experiences. The learner attaches meaning to new information based on what they already know. Bruner believed knowledge acquired in this way is better retained than information that is simply passed down from an instructor.

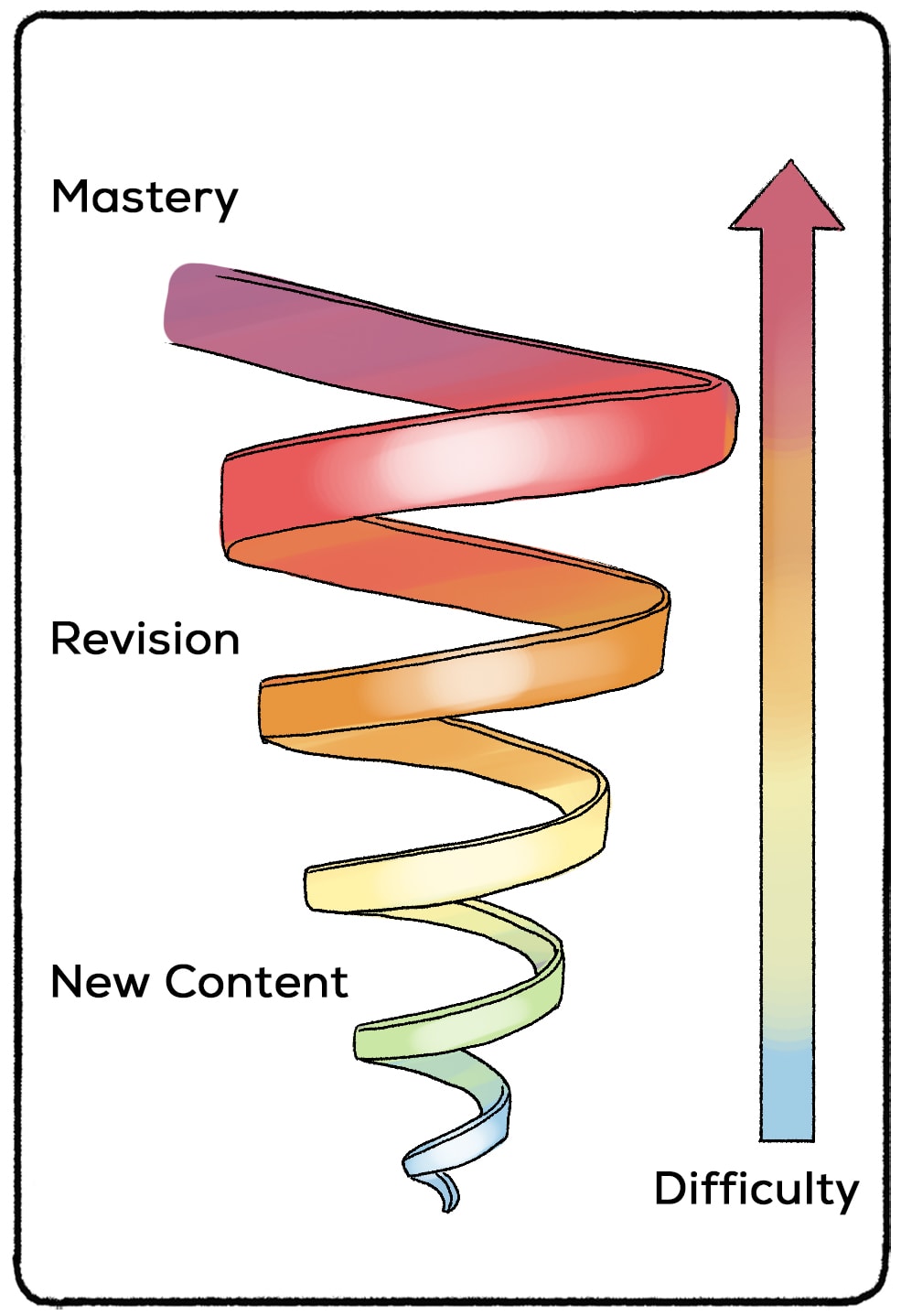

The Spiral Curriculum

Unlike Piaget's theory of cognitive development, Bruner did not believe that children have to reach a particular age or maturational level in order to grasp certain concepts. Instead, he argued that any subject matter, including complex concepts, can be presented in a form that is simple enough for a learner at any age to understand. He is famously quoted as saying, “any subject can be taught effectively in some intellectually honest form to any child at any stage of development.”

In line with this view, Bruner advocated a spiral curriculum in which the same subject matter is taught at various levels with increasing depth and breadth. At first, only basic principles are presented but as the learner advances to higher levels of education, the subject is revisited with additional details being presented. Learning therefore takes place in a spiral fashion with the learner continually building on what he or she has already learned.

Bruner believed learning is most effective when material is presented in sequence from enactive (using manipulatives), to iconic (using illustrations and diagrams), to symbolic (using language and other symbols). For example, complex concepts such as the addition of fractions can be taught in enactive form to very young children using tangible fraction circles. As children mature, the other modes of representation can be employed to teach more complex aspects of the topic.

Jerome Bruner's Scaffolding Theory

Jerome Bruner also advocated a process known as scaffolding, in which adults provide ongoing support as children attempt to solve a problem or master a task they are not quite able to manage on their own. The adult provides temporary assistance to maximize the child’s growth.

Just as how a literal scaffold temporarily supports the building of a tall structure. Adults can provide a scaffold in various ways, for example by:

- helping children to maintain interest in the task at hand

- drawing their attention to important bits of information they might have overlooked

- Breaking down complex tasks into smaller, more manageable ones

- modeling certain aspects of a skill to be learned

- explaining unfamiliar terms

- highlighting errors

- providing prompts or hints

The aim of scaffolding is to provide just enough support so that the child is able to improve his knowledge, move on to the next stage of the task and arrive at a solution for himself. The assistance provided must be continually adjusted to meet the changing needs of the learner. At first, the child may be very dependent on the support of the adult but as he or she acquires the relevant skills and knowledge, the support can be gradually decreased and withdrawn completely over time.

Applications of Bruner’s Theories

Many aspects of Bruner’s theories have found application in the field of education, influencing both policy and curriculum design. Some schools, such as those in Singapore, have adopted a C-P-A (concrete-pictoral-abstract) approach to teaching subjects such as mathematics and science. Teachers who follow this approach introduce topics using concrete materials before progressing to visual and then abstract representations. This is in line with Bruner’s belief that instruction should move sequentially from enactive to iconic to symbolic modes of representation.

Bruner’s concept of the spiral curriculum has also influenced the educational philosophy of schools in several countries, including China and the United States. In these schools, the same topics are revisited periodically across several grades. Teachers make a deliberate effort to connect new information with previous knowledge, building on what the learner already knows in order to deepen understanding.

Scaffolding is another aspect of Bruner’s theories which some teachers have tried to implement in the classroom. The concept has also been applied to peer-to-peer learning, with more advanced students assisting weaker peers.

Criticisms of Bruner’s Theories

Although Bruner’s concepts have greatly contributed to education policy in several countries, critics have raised doubts regarding the practicality of some of his ideas. For example, while scaffolding and spiraling offer several advantages to the learner, their effectiveness depends greatly on how knowledgeable teachers are. In the case of scaffolding, teachers must know when to intervene, when to step back and how to motivate effectively. They must also be aware of each child’s changing needs, which can be difficult in a large classroom where the teacher is not able to monitor each child’s progress individually.

For spiraling to be effective, teachers must also be familiar with the child’s existing knowledge base. If teachers repeat or re-teach information that students already know, they run the risk of students losing interest in the topic.On the other hand, if teachers wrongly assume that students remember the fundamental concepts of a topic taught in previous grades, they may frustrate learners when more advanced concepts are introduced.

Discovery learning also presents challenges in the classroom since misconceptions sometimes arise among students as they attempt to construct meaning for themselves. These misconceptions may go undetected by teachers, especially in larger settings. Discovery learning also requires large amounts of resources which may not be readily available in some schools. It can also be a challenge to implement this form of learning in settings where behavior management is a problem.

Other critics note that discovery learning may not be suitable for students who prefer a more traditional approach to teaching and learning. As some have pointed out, there is no evidence to show that all students are effective at creating meaning on their own. Some students prefer structure and become frustrated when the demands of a task are not clear.

One of Bruner’s foremost critics, David Ausubel, further argued that young children in particular need direct instruction and that the volume of information to be learned at school leaves little time for discovery. Other critics agree with Ausubel, noting that a child-centered, process-oriented approach might not be ideal when teaching basic skills such as reading and writing. Research also suggests that when teaching students with learning difficulties, a direct approach is more effective for introducing new information and skills.

Some critics have also taken issue with Bruner’s claim that any subject matter can be taught at any age in some ‘honest form.’ These critics argue that children need to achieve a certain level of maturity in order to handle some concepts. Bruner himself criticized his own claim over his failure to explain what he meant by the term ‘honest.’

Jerome Bruner's Books, Awards, and Accomplishments

Bruner authored or co-authored many scholarly papers and several bestselling books throughout his long career. Some of his most significant works are listed below.

Books:

- Mandate from the People (1944)

- A Study of Thinking (1956)

- The Process of Education (1960)

- On Knowing: Essays for the Left Hand (1962)

- Toward a Theory of Instruction (1966)

- Processes of Cognitive Growth: Infancy (1968)

- The Relevance of Education (1971)

- Communication as Language (1982)

- Child’s Talk (1983)

- In Search of Mind: Essays in Autobiography, 1983

- Actual Minds, Possible Worlds (1986)

- Acts of Meaning (1990)

- The Culture of Education (1996)

- Minding the Law (2000)

- Making Stories: Law, Literature, Life (2002).

Jerome Bruner has received twenty-four honorary doctoral degrees from established universities around the world. Some of these institutions include:

- Harvard University

- Yale University

- Columbia University

- Northwestern University

- Free University of Berlin

- University of Geneva

- University of California, Berkeley

- The New School

- National University of Rosario

- ISPA – Instituto Universitário

- The Sorbonne

- Temple University

- North Michigan University

Bruner was also given several awards for his contributions to the field of psychology. A few of these awards include:

- Distinguished Scientific Award from the American Psychological Association

- Distinguished Contributions to Research in Education Award from the American Educational Research Association

- International Balzan Prize

- CIBA Gold Medal for Distinguished Research

- Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

Personal Life

Jerome Bruner met his first wife, Katherine Frost, at Harvard. The couple had a son named Whitley and a daughter named Jane. However, Bruner and Katherine divorced after he returned from Europe at the close of World War II. Bruner’s second marriage to Blanche Ames Marshall also ended in divorce. His third wife, Carol Feldman, passed away in 2006.

Is Jerome Bruner Still Alive?

Jerome Bruner died on Sunday June 5, 2016 at his Greenwich Village loft in Manhattan. He was 100 years old. He is survived by his partner Dr. Eleanor Fox, his two children, and three grandchildren.

References

American Psychological Association. (2002). Eminent psychologists of the 20th century. Monitor on Psychology, 33 (7) 29. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/monitor/julaug02/eminent

Association for Psychological Science. (2016, December 20). Remembering Jerome Bruner. Observer. Retrieved from https://www.psychologicalscience.org/observer/remembering-jerome-bruner

Aubrey, K., & Riley, A. (2019). Understanding and using educational theories (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Carey, B. (2016, June 8). Jerome S. Bruner, who shaped understanding of the young mind, dies at 100. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/09/science/jerome-s-bruner-who-shaped-understanding-of-the-young-mind-dies-at-100.html

Crace, J. (2007, March 27). Jerome Bruner: The lesson of the story. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/education/2007/mar/27/academicexperts.highereducationprofile

Encyclopedia Britannica. (n.d.). Jerome Bruner. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Jerome-Bruner

Harvard University. (n.d.). Jerome Bruner. Retrieved from https://psychology.fas.harvard.edu/people/jerome-bruner

NYU Law News. (2010, November 4). Jerome Bruner receives honorary doctorate at international psychology congress in Argentina. Retrieved from https://www.law.nyu.edu/news/BRUNER_DEGREE_ARGENTINA

NYU Law News. (2016, June 6). In memoriam: Jerome Bruner, 1915-2016. Retrieved from https://www.law.nyu.edu/news/in-memoriam-jerome-bruner

Rich, G. J. (2013). Bruner, Jerome S. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/9781118339893.wbeccp065

Schudel, M. (2016, June 7). Jerome S. Bruner, influential psychologist of perception, dies at 100. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/jerome-s-bruner-influential-psychologist-of-perception-dies-at-100/2016/06/07/033e5870-2cc3-11e6-9b37-42985f6a265c_story.html

Social Psychology Network. (2008, November 14). Jerome Bruner: In memoriam. Retrieved from https://bruner.socialpsychology.org/

Tassoni, P., & Beith, K. (2005). Diploma in child care and education. Jordan Hill, Oxford: Heinemann Educational Publishers.

Westwood, P. (2004). Learning and learning difficulties: A handbook for teachers. Camberwell, Victoria: ACER Press.