John Bowlby is also one of the most cited psychologists of all time. Want to learn more about him? You are in the right place.

Who is John Bowlby?

John Bowlby was a British psychologist, psychoanalyst, and psychiatrist. He is widely recognized as the founder of Attachment Theory, which is still regarded as a valid theory. Bowlby believed children have an inborn tendency to develop a close emotional bond with their caregivers.

John Bowlby's Early Years

Edward John Mostyn Bowlby was born on February 26, 1907, in London. His parents were Sir Anthony Alfred Bowlby and Mary Bridget Mostyn. John Bowlby was the fourth of six children. His siblings were Winnie, Marion, Tony, Jim, and Evelyn.

John Bowlby Parents

Bowlby was raised in a Victorian upper-middle-class family. His father—Sir Anthony—was a baronet, a high-ranking officer in the British army, and a surgeon on the King’s medical staff. Sir Anthony was known to have a strong personality and a tendency to stick to his decisions if he believed they were right. John’s mother—Mary—was homeschooled and came from a middle-class family.

Bowlby’s parents got married in 1898. At that time in British society, it was common for families of high social standing to hire a nanny to raise the children. The general belief was that the children would become spoiled if they were given too much attention and affection.

The Bowlby children spent most of their day in the nursery. It was located on the top floor of the house and isolated from the other rooms. As a result, Bowlby saw his mother for only one hour each day after teatime. He usually only saw his father on Sundays due to Sir Anthony’s work in the military.

In the summer, Bowlby’s mother tried to make more time for him and his siblings. Mary had a deep love for nature which she tried to pass on to her children. She encouraged them to learn how to ride, shoot, fish, and identify birds, flowers, and butterflies. It is possible that Mary sparked John’s appreciation for nature during his childhood as well as his future interest in ethology.

With his parents usually unavailable, Bowlby was raised by Nanny Friend and her two nursemaids. He was particularly close to nursemaid Minnie, who served as the primary caregiver for the children. However, nursemaid Minnie left the household when Bowlby was four years old. Bowlby later stated that he felt as if he had lost a mother.

With the departure of nursemaid Minnie, Nanny Friend took charge of Bowlby and his siblings. She did not develop very close relationships with the children though, as she was more sarcastic and colder than nursemaid Minnie. The Bowlby children were homeschooled by a governess after they turned six years old. Tony and John later attended day school in London.

John Bowlby's Childhood in World War I

World War I had a big impact on the Bowlby family. It kept Sir Anthony away from his family and in 1918 John and Tony were sent away to a boarding school called Lindisfarne. Although sending kids to boarding school was a common practice of the time, Bowlby’s parents also wanted to keep their children safe as London had suffered air raids and bombings in 1917. Bowlby described his experience at Lindisfarne as terrible and traumatic.

Separation was a recurring theme in John Bowlby’s childhood. In addition to experiencing separation from his parents, nursemaid Minnie, and his family (after being sent to boarding school), he also lost his beloved godfather who passed away. This upbringing made Bowlby very sensitive to the suffering of children when he became an adult. His childhood experiences also likely influenced his research on separation later in life.

Educational Background

Bowlby joined the Britannia Royal Naval College in 1921. At the time, he wanted to become a naval officer. In 1925, he enrolled at Trinity College, Cambridge, after his father encouraged him to study medicine. However, Bowlby did not have a passion for the natural sciences or anatomy. By the time he graduated from Trinity College in 1928, he had changed his focus from medicine to developmental psychology.

After graduating from Cambridge, Bowlby rejected an offer to become a science teacher at St. Paul’s boys’ school in London. He was eager to expand his understanding in the fields of developmental psychology and education. He accepted a position at Dunhurst, the junior school of Bedales, which emphasized student freedom, self-expression, and learning by doing. Despite getting along very well with the young children at Dunhurst, he left the position after six months as budgetary restrictions meant he had limited time with the students.

Bowlby later went to another progressive school called Priory Gates. This school accepted maladjusted students whose emotional issues could be traced back to their family life. Bowlby described his time at Priory Gates as “the most valuable six months of my life.” The experience taught him that many of the problems people have today may be due to problems in early childhood.

College

When he was 22 years old, Bowlby registered at University College Hospital in London. While he was studying medicine, he also enrolled at the Institute for Psychoanalysis. Bowlby earned his medical degree at the age of 26. He then trained in psychiatry at the Maudsley Hospital and qualified as a psychoanalyst in 1936 at the age of 30.

Bowlby worked as a psychiatrist at the London Child Guidance Clinic from 1937 to 1940. It was a school for maladjusted children. During his time at the clinic Bowlby examined 44 children who had a history of stealing. In his first published work, Forty-four Juvenile Thieves, Bowlby highlighted that a high percentage of children with emotional, mental, and behavioral issues experienced early and prolonged separation from their primary caregiver.

Military Experience

Six months after the start of World War II, Bowlby joined the British army. He served as a lieutenant colonel in the Royal Army Medical Corps. Bowlby conducted research on how to use psychology to help with officer selections. He also continued to help children who had become separated from their families due to the war.

Bowlby’s time in the military brought him into contact with people who worked at the Tavistock Clinic. After the war, he accepted the offer to become the clinic’s deputy director. While at Tavistock, Bowlby supervised the work of Mary Ainsworth in the 1950s. Ainsworth would later play a key role in helping Bowlby develop and test his attachment theory.

In 1950, Bowlby was invited to work with the World Health Organization as a mental health consultant. This was a highlight of his career. Bowlby was asked to investigate the mental health of homeless children after World War II. In 1951 he published Maternal Care and Mental Health, in which he emphasized the importance of maternal care in a child’s healthy development.

John Bowlby’s Attachment Theory

Bowlby’s experience in treating maladjusted children at the London Child Guidance Clinic led him to consider the child-mother relationship and how it may impact cognitive, social, and emotional development. He was particularly interested in how separating an infant from its mother for a long time seemed to predict problems for the child later in life. Bowlby was also heavily influenced by a 1935 study in which Konrad Lorenz showed that newly hatched ducklings had an inborn ability to form attachments and boost survival. All of these experiences and influences helped Bowlby to develop his evolutionary theory of attachment.

What Is Attachment?

Attachment refers to the strong emotional bond that connects two people together. Bowlby believed that attachment processes are adaptive, that is, essential for the survival and well-being of infants. From an evolutionary perspective, infants who remained close to their parents had a greater chance of being protected from predators and other threats in their environment. Hence, they were more likely to survive than infants who ventured away.

What Did John Bowlby Say About Attachment?

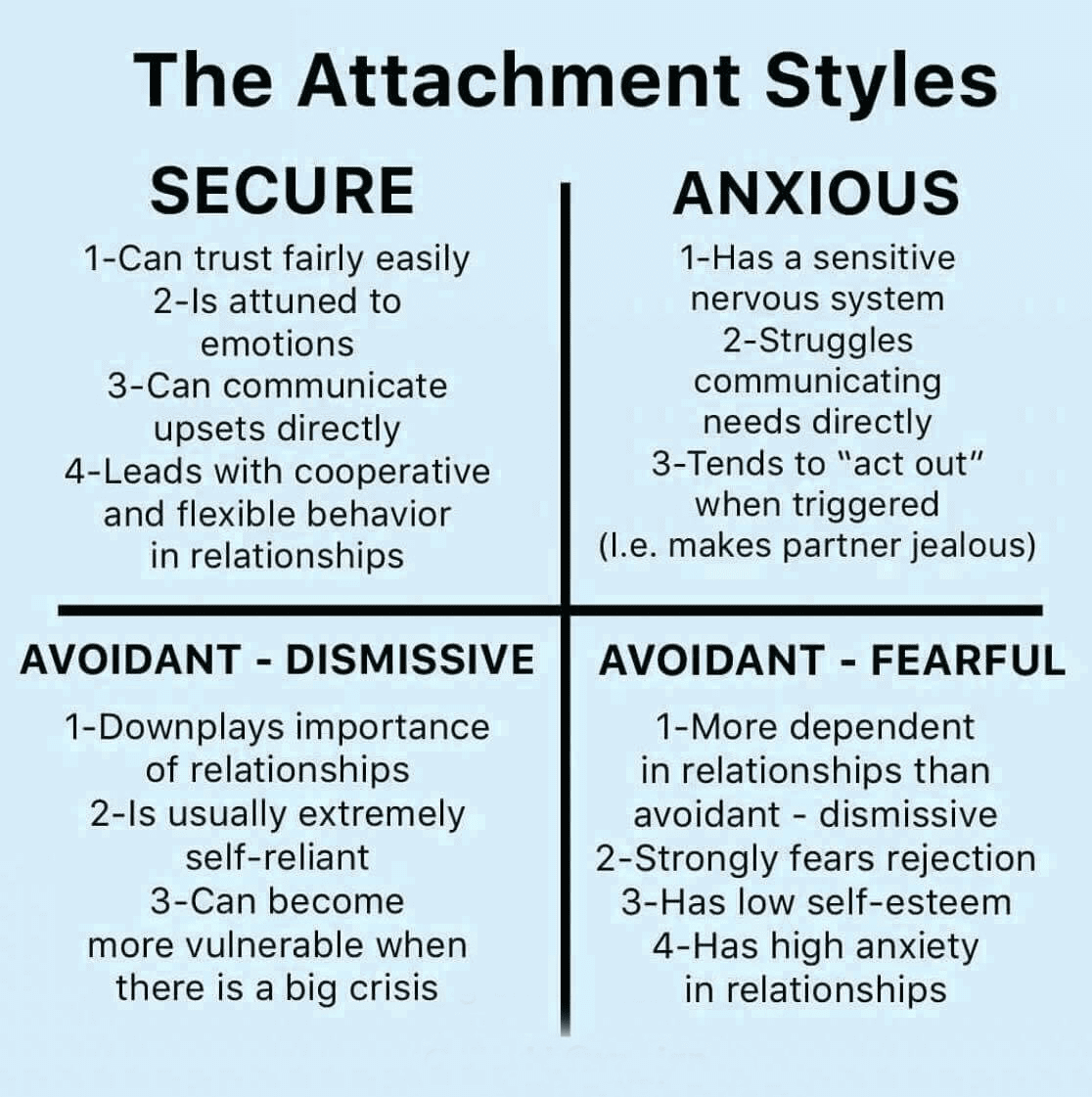

The main idea behind Bowlby’s attachment theory is that infants are born with a desire to form a close affective bond with one particular caregiver, usually their mother. Bowlby referred to this tendency to attach to one individual in particular as ‘monotropy.’ He believed infants are programmed to maintain proximity and contact with their mothers through instinctive behaviors such as crying, cooing, smiling, crawling and gripping. Bowlby called these actions ‘social releasers’ because they released or triggered instinctive caring behaviors in adults.

As infants display a range of social releasers and their mother responds to them, an attachment is formed between the two. Mothers who are consistently responsive to the needs of their babies make their babies feel more secure. When the baby has a secure base, he or she feels safe enough to explore and learn about the world. In Bowlby’s view, such a baby is likely to grow into a well-functioning adult.

Maternal Deprivation Hypothesis

Bowlby suggested that early experiences with one’s mother have long-lasting effects on one’s social, emotional and cognitive functioning. He specified a sensitive period lasting from birth to about two years of age, when the continuous presence of the most significant attachment figure is particularly crucial. If a stable attachment is not formed during this time, Bowlby believed it would be much harder for the child to form an attachment later on.

According to Bowlby’s maternal deprivation hypothesis, failure to form an attachment during the sensitive period, or a disruption in such an attachment, will likely result in serious consequences later in life. These include what Bowlby termed ‘affectionless psychopathy,’ a condition marked by difficulty forming close, meaningful relationships, a lack of concern for others, and an inability to experience guilt or remorse. Bowlby also specified low intellectual functioning as another consequence of maternal deprivation.

The Forty-Four Thieves Study

Bowlby sought to provide evidence for his maternal deprivation hypothesis through what is commonly referred to as the Forty-Four Thieves Study. The research was conducted between 1936 and 1939 with a sample of 44 juvenile delinquents who had been referred to the Child Guidance Clinic where Bowlby worked. The teens had all been involved in stealing. Interviews were conducted with the teens and their families to determine if they had experienced prolonged separation from their primary caregivers early in life, and whether they displayed symptoms of affectionless psychopathy. A control group of 44 non-delinquent teens was also included in the study.

Of the 44 juvenile delinquents, 14 were identified as ‘affectionless psychopaths’ and of these, 12 (86%) had experienced prolonged separation from their mothers before age 2. Of the 30 delinquents not labeled as ‘affectionless psychopaths,’ only 5 (17%) had experienced early maternal separation. As for the control group of non-delinquents, only 2 (5%) had been separated from their primary caregiver early in life. Based on these results, Bowlby concluded that early maternal separation results in significant and permanent psychological damage.

Internal Working Models

Another important aspect of Bowlby’s attachment theory is his concept of an internal working model. This refers to a mental representation of the infant’s earliest attachment relationship. Bowlby believed this internal representation profoundly affects the child’s relationships later in life, including their relationships with their own children.

According to Bowlby, if a child’s internal working model is of a relationship with a loving, attentive and reliable caregiver, he or she will likely reproduce this pattern of responding as a parent. On the other hand, if the child internalized a working model of a relationship with an abusive or neglectful caregiver, there is a strong likelihood that he or she will behave similarly as a parent. The presence of internal working models would help to explain why certain patterns of child-rearing are repeated throughout several generations of a family.

Applications of Bowlby’s Attachment Theory

Bowlby’s attachment theory highlights the importance of early relationships for future development and well-being. The major tenets of his theory have served to guide practitioners and policy makers in various domains, including:

- Healthcare

- Counseling and psychotherapy

- Parenting

- Social work

Healthcare

In many healthcare facilities and birthing centers, the importance of contact between mother and child in the first few hours of life is now being emphasized as this is believed to foster attachment. The establishment of Mother and Baby Units (MBU) in countries like the UK has also been guided by attachment theory. MBUs are in-patient units which cater to women who develop mental health issues in the year following the birth of their child. The units are designed to keep mother and baby together and to nurture the bond between the two, while allowing the mother to receive necessary treatment.

Attachment theory was also influential in guiding hospital policy regarding the visiting rights of parents whose children are hospitalized. In many places, parents and primary caregivers are now allowed unlimited visiting rights, with one parent often being allowed to stay overnight in the child’s hospital room.

Counseling and Psychotherapy

Therapists who work within the framework of attachment theory try to build a close and consistent therapeutic relationship with their client. In this way, the therapist becomes a reliable attachment figure for the client, a secure base from which he or she feels comfortable exploring past experiences and new patterns of behavior. By evaluating the early parent-child relationship, therapists can help clients to understand how past experiences with attachment figures have influenced their coping strategies, emotional challenges, and current relationships.

Social work

In the early 1950’s, Bowlby prepared a report on behalf of the World Health Organization outlining the impact of maternal deprivation on homeless children. Based on the negative outcomes reported, Bowlby argued against children being separated from their mothers without sound justification, such as abuse or neglect. His arguments have greatly influenced social work practice since then.

Parenting

Several attachment-based parenting programs have been developed for use with at-risk families. These programs are designed to improve interaction between infants and their caregivers through training in basic attachment principles. For example, parents may learn how their responses to their infant’s social releasers can have long-lasting effects on that child’s development.

Criticisms of Bowlby’s Attachment Theory

Several aspects of Bowlby’s theories, such as the existence of social releasers and internal working models, have been supported by research. However, as with all theories, there are limitations.

Material Deprivation and Attachment

A major criticism is that Bowlby overemphasized the role of maternal attachment in a child’s development. Although he did not rule out the possibility of other attachments, he believed the child’s attachment to its mother is the earliest and most significant bond formed. Studies have shown, however, that a child’s attachment to his or her father can also have a significant impact on development, especially in families where both mother and father are present. Bowlby’s idea of monotropy has also been challenged by studies which show that infants can develop equally strong attachments to more than one individual.

The Forty-Four Thieves Study, which Bowbly cited as evidence for his maternal deprivation hypothesis, has also been criticized on several grounds. One criticism concerns the possibility of researcher bias. Much of the data for the study - the interviews and psychiatric evaluations - were conducted by Bowlby himself. He made the diagnoses of affectionless psychopathy and knew which participants belonged to the delinquent group versus the control group. Bowlby’s own expectations could therefore have influenced the data collection process and ultimately, the findings of the study.

Another limitation of the study relates to the type of data collected. Information regarding maternal separation was gathered through retrospective accounts, meaning that respondents had to recall periods of separation. If participants’ memories were not accurate,or if they did not respond honestly, the resulting data would have been compromised.

Based on the findings of that study, Bowlby concluded that maternal deprivation results in affectionless psychopathy. This is a classic example of mistaking correlation for causation. The results merely showed an association between the two variables but did not prove that one caused the other. Many other factors could have accounted for the diagnosis of affectionless psychopathy, including the family’s socioeconomic status, level of education, exposure to abuse etc.

A well-known critic of Bowlby’s work, Michael Rutter, further argued that Bowlby failed to make a distinction between what he called ‘privation’ and deprivation. According to Rutter, privation is a complete failure to form an emotional attachment, while deprivation is a disruption in an attachment that was already formed, for example through separation or death. Rutter believed that a distinction is necessary since privation and deprivation have different effects, with the former resulting in more serious consequences.

Finally, other critics have argued that children are more resilient than Bowlby’s maternal deprivation hypothesis suggests. Many children go on to lead productive, well-adjusted lives despite early disadvantages and separation from primary caregivers. In addition, whereas Bowlby felt that the effects of maternal deprivation are lasting, other theorists argue that these effects can be overcome later in life with appropriate care and support.

John Bowlby's Books, Awards, and Accomplishments

Bowlby published six books on his attachment research as well as a biography of Charles Darwin. His works are listed below:

- Bowlby, J. Maternal Care and Mental Health. London: Jason Aronson, 1950.

- Bowlby, J. Child Care and the Growth of Love. London: Penguin Books, 1976.

- Bowlby, J. Attachment. New York: Basic Books, 1999.

- Bowlby, J. Separation: Anxiety and Anger. London: Hogarth Press, 1973.

- Bowlby, J. Loss: Sadness and Depression. London: Hogarth Press, 1980.

- Bowlby, J. A Secure Base: Parent-Child Attachment and Healthy Human Development. London: Routledge, 1988.

- Bowlby, J. Charles Darwin: A New Life. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1992 (published posthumously)

He also received the following awards for his contributions to psychology:

- American Psychological Association’s Award for Distinguished Scientific Contributions (1989)

- Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians (FRCP)

- Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (CBE)

John Bowlby Children and Personal Life

On April 16, 1938, John Bowlby married Ursula Longstaff. Ursula was the daughter of Dr. Tom George Longstaff—a surgeon. The couple raised four children together.

Is John Bowlby Still Alive?

John Bowlby died in Scotland on September 2, 1990.

Bowlby inspired many of his contemporaries and left a solid foundation for future researchers to expand upon his theories. His research has made a permanent impression on a number of fields, including psychology, mental health treatment, parenting, child care, and education.

References

American Psychological Association. (1990). Awards for distinguished scientific contributions: Mary d. salter ainsworth and john bowlby. American Psychological Association. Retrieved from https://psycnet.apa.org/buy/2009-08862-001

Beckwith, H. (2018). What is attachment theory used for? Retrieved from

https://www.acamh.org/blog/attachment-theory-applications/

Bretherton, I. (1992). The origins of attachment theory: John bowlby and mary ainsworth. Developmental Psychology, 28, 759-775. Retrieved from http://www.psychology.sunysb.edu/attachment/online/inge_origins.pdf

Comer, R. & Gould, E. (2011). Psychology around us. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

New World Encyclopedia. (2016). John bowlby. In New World Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/John_Bowlby

Russel, J. & Jarvis, M. (2003). Angles on applied psychology. Cheltenham, England: Nelson Thornes.

van der Horst, F. C. P. (2011). John bowlby - from psychoanalysis to ethology: Unravelling the roots of attachment theory. John Wiley & Sons.

Van Dijken, S. (n.d.). John bowlby. Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-Bowlby

Van Dijken, S., van der Veer, R., van Iizendoorn, M. H. & Kuipers, H. J. (1998). Bowlby before Bowlby: The sources of an intellectual departure in psychoanalysis and psychology. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 34 (3), 247– 269. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/28639641_Bowlby_before_Bowlby_The_sources_of_an_intellectual_departure_in_psychoanalysis_and_psychology