Mary Ainsworth was an American Canadian developmental psychologist. For most of her career, she studied the relationship between infants and their primary caregivers. Ainsworth is best known for her contributions to Attachment Theory and for developing the Strange Situation test. She is also one of the top 100 most frequently cited psychologists in history.

Mary Ainsworth's Childhood

Mary Dinsmore Salter was born on December 1, 1913 in the village of Glendale, Ohio. Her parents were Charles and Mary Salter. She was raised in a middle-class family and had two younger sisters. Salter later acquired the surname “Ainsworth” through marriage.

Charles and Mary Salter graduated from Dickinson College—the first college founded after the formation of the United States. Charles had a master’s degree in history and worked in manufacturing. Mary was a trained nurse who chose to stay home to care for her family. Both parents were very eager to give their daughters a good education.

Mary Dinsmore Salter showed a love for learning when she was very young. At age three, she started reading. Her parents would take her to the local library each week so she could get new books that were appropriate for her level. In 1918, when Salter was five years old, her family moved to Canada after her father was asked to become the president of a manufacturing firm in Toronto.

Salter was a brilliant student who got good grades in school. When she was 15 years of age, she went to the library and borrowed the book “Character and the Conduct of Life.” It was written by American psychologist William McDougall. After reading the book, Salter became very interested in psychology and decided to study more about the field.

Although both her parents encouraged her to excel academically, Salter later revealed that her relationship with each parent was very different. She was much closer to her father. During her childhood her father would sing to her and tuck her in at night. Salter believed her mother was envious of the connection she had with her father and tried to interfere with it.

Educational Background

In the fall of 1929, Mary Salter was accepted at the University of Toronto. She was 16 years old. Salter was one of only five students who were offered admission to the psychology honors program. She received her bachelor’s degree in 1935.

After earning her first degree, Salter decided to continue her education at the University of Toronto. She earned her master’s degree in 1936. Three years later, Salter earned her doctoral degree after presenting the thesis “An Evaluation of Adjustment Based on the Concept of Security.” After receiving her PhD in 1939, she taught at the University of Toronto for three years.

Mary Salter joined the Canadian Women’s Army Corp in 1942 to assist the Allied Powers during World War II. She initially served as an Army Examiner who performed clinical evaluations and personnel assessments. The nature of her work helped her to develop excellent clinical and diagnostic skills and she was soon asked to serve as an Advisor to the Director of Personnel Selection of the Canadian Women’s Army Corps. By 1945, Salter reached the rank of Major.

World War II ended in 1945 and Salter returned to the University of Toronto in 1946 as an Assistant Professor. Her goal was to research and teach personality psychology. In 1950, she married Leonard Ainsworth, who was a World War II veteran and a graduate student in the university’s psychology department. She adopted her husband’s surname and eventually became known globally as “Mary Ainsworth.”

In 1950, Leonard decided to go to London to complete his PhD and Mary went with him. While in London she worked under the guidance of psychologist John Bowlby at the Tavistock Clinic. Mary Ainsworth and John Bowlby conducted research on maternal-infant attachments. They found that disrupted mother-child bonds have a negative effect on child personality development.

In 1954, Leonard went to Uganda after he accepted a position at the East African Institute of Social Research. Mary had plans to conduct a longitudinal field study of mother-infant attachments in a natural setting, so she accompanied Leonard to Uganda to further her research. She was especially interested in mother-infant interactions during the weaning process. Mary made an effort to learn the local language and conducted interviews with families from six neighboring villages.

After spending two years in Uganda, Leonard accepted an offer to become a forensic psychologist in Baltimore and Mary followed him to the United States. After giving a talk at the Johns Hopkins University, she accepted a position as an associate professor of developmental psychology. Mary also worked at the Sheppard and Enoch Pratt Hospital, where she provided psychological services for two days each week.

During her time at Johns Hopkins, Mary kept in touch with John Bowlby who was still based in London. However, they now worked together as equals and offered helpful comments on each other’s research. In 1960, Leonard and Mary went through a very painful divorce. But despite the emotional challenges, she was able to remain focused on her work.

Mary presented her findings from the Uganda study in London at the Tavistock Mother-Infant Interaction Study Group. However, a number of the researchers there were unimpressed and questioned her definition of “attachment.” Mary used the lukewarm response as motivation to create an assessment to measure the attachment between mothers and their children. She catalogued specific behaviors infants displayed in different settings and eventually developed the “Strange Situation Test” during her time at Johns Hopkins.

The Strange Situation Test

The strange situation test was developed by Ainsworth and her colleagues to evaluate the nature of attachment relationships between infants and their caregivers. The experimental procedure consists of eight episodes involving brief separations from, and reunions with the caregiver, as well as exposure to a stranger. All episodes occur within the context of an unfamiliar playroom.

Ainsworth’s study involved a sample of 100 infants between the ages of 12 and 18 months, all from middle-income American families. Each infant was exposed to the following eight situations:

- Mother and infant are introduced to the playroom by the researcher

- Mother and infant are left alone in the playroom; the child is allowed to explore the room and play with the toys

- A stranger enters the room, talks to the mother and attempts to interact with the infant

- Mother leaves the room discreetly while the stranger continues to interact with the infant

- Mother returns to the playroom and the stranger leaves quietly

- Mother leaves the playroom and the infant is left alone

- The stranger returns to the playroom and attempts to interact with the infant

- Mother returns and the stranger leaves discreetly

In Ainsworth’s study, each episode lasted about 3 minutes, with the exception of the first episode which was approximately 30 seconds long. Trained observers took careful note of the infant’s reactions from behind a two-way mirror. The child’s behavior in the presence and absence of the caregiver, in the presence of the stranger, and when reunited with the caregiver were all recorded. For example, observers noted the child’s level of play and exploration in the presence of the mother and stranger, the amount of crying in the absence of the mother, and the ease with which the infant was consoled when in distress.

Ainsworth’s Attachment Styles

Ainsworth believed attachment styles resulted from the infant’s early interactions with the mother, an idea which she termed the ‘maternal sensitivity hypothesis.’ A sensitive mother was defined as one who accurately perceives the needs of her child and responds to them promptly and appropriately. Ainsworth believed maternal sensitivity was necessary for healthy attachment.

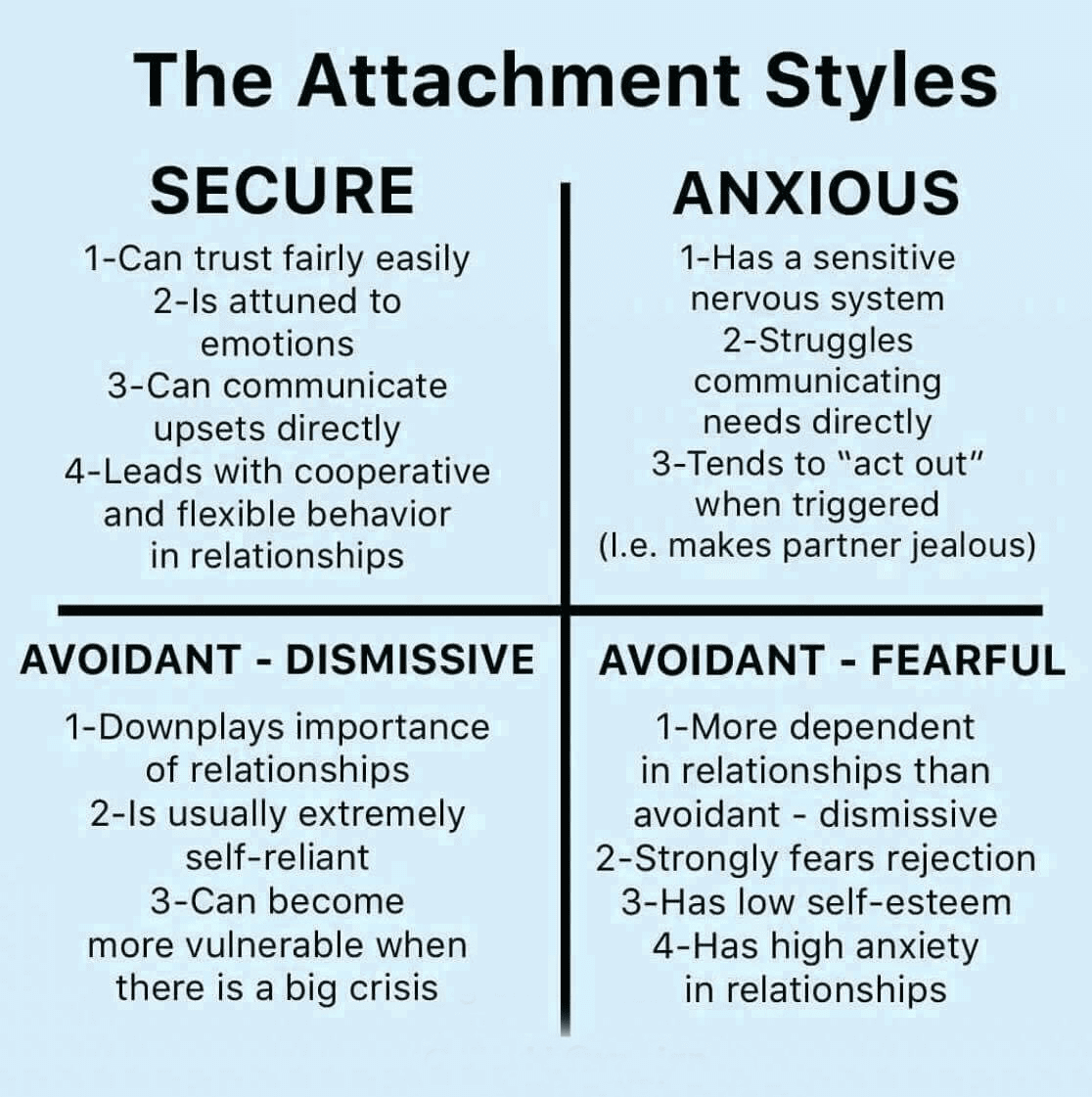

Based on her research using the strange situation procedure, Ainsworth identified three distinct attachment styles:

- Secure attachment (Type B) - Infants who are securely attached perceive the attachment figure as a secure base from which they can confidently explore unfamiliar environments. When separated from their caregivers, they display a moderate degree of distress (separation anxiety) but are easily comforted upon the caregiver’s return. The reunion is usually a joyous one. In times of distress or anxiety, these infants actively seek out their caregivers, confident that they will respond appropriately to their needs. They tend to avoid strangers when alone with them but will interact with unfamiliar individuals in the presence of their caregiver. Most of the infants (70%) studied by Ainsworth displayed this form of attachment.

- Parents of children who are securely attached display a high level of warmth and are sensitive to their children's needs. These children learn that they can depend on their caregivers for comfort and support. If separated, they do not become unduly anxious as they are confident of their caregiver’s return

- Insecure-avoidant attachment (Type A) - Infants with this type of attachment have a tendency to avoid or ignore their caregiver. They show very little anxiety in the absence of the attachment figure and do not seek comfort from him/her when in distress. They also show little interest in the caregiver when reunited after a period of separation. The response of such infants to their caregiver is not much different from their response to a complete stranger. In both situations, they maintain an obvious degree of emotional and physical distance. About 20% of the infants in Ainsworth’s study displayed this form of attachment.

- According to Ainsworth, insecure-avoidant children tend to have caregivers who are largely unresponsive to their needs. Since the attachment figure is usually unavailable or rejecting, the child learns that there is little benefit in communicating his or her needs.

- Insecure-resistant attachment (Type C) - The remaining 10% of infants in Ainsworth’s study were said to have an insecure-resistant (or insecure-ambivalent) form of attachment. These infants fail to develop a sense of security in the presence of their caregiver and are hesitant to move away in order to explore unfamiliar surroundings. They tend to be very clingy, sticking close to the attachment figure. These children display the highest level of emotional distress in the absence of their caregiver and in the presence of a stranger (stranger anxiety). When reunited with their attachment figure, they often seem unsure of how to respond; they may approach the caregiver to seek comfort, but at the same time, show signs of resentment toward him/her. They may even resist the caregiver’s efforts to console them. Not surprisingly, these children are often quite difficult to soothe when in distress.

Children who develop this form of attachment usually have caregivers who are inconsistent in responding to their needs. In some cases, the parent responds readily to the child’s cues; other times, the child is ignored. This results in ambivalence on the part of the child as he/she can never predict the type of response he/she will receive.

Applications of Ainsworth’s Attachment Theory

Ainsworth’s theory of attachment has been applied in a variety of contexts. These include:

- Child-rearing - Parenting manuals and programs often advocate sensitive parenting with the goal of increasing the security of the parent-child attachment, or minimizing factors that could lead to insecure attachment.

- Psychotherapy - Several intervention programs used in family therapy are based on the idea that secure attachment with one’s primary caregiver(s) is necessary for current and future well-being. An individual’s attachment style in early life may also be used as a framework for understanding relationship issues in adulthood.

- The legal system - The security of a child’s attachment to one or more caregivers is often considered when making decisions about the welfare of the child. In custody disputes, for example, counselors, psychologists, social workers and other health-care professionals may emphasize the importance of sensitive parenting when testifying before the court.

- Public policy - In some countries, national policies and programs have been developed in order to encourage sensitive parenting. These include policies and programs regarding breastfeeding, co-sleeping and paid maternity leave.

- Education - In some early educational settings, such as daycare centers and kindergartens, teachers and care providers may be encouraged to apply aspects of attachment theory to their interactions with children.

Criticism of Ainsworth’s Methodology and Theory

Ainsworth’s strange situation test has proven to be a valuable tool for studying attachment, but there are several limitations to this procedure. For one thing, it involves a laboratory setting which some critics believe does not adequately reflect real life situations. Some argue, for example, that the mother may act differently towards her child in a setting where she knows she is being observed, as opposed to when she is in the comfort of her own home.

The procedure has also been criticized on ethical grounds since it involves exposing infants to a degree of stress (including separation anxiety and stranger anxiety). Some believe this exposure is unjustified and may even cause psychological harm. However, not all psychologists agree. Some point out that the strange situation test actually reflects everyday life in which the caregiver may sometimes leave an infant in a new environment, or in the care of an unfamiliar individual, for short periods of time.

Other critics point out that Ainsworth’s initial study only involved infants from middle-class families in the United States and therefore cannot be applied to children from other socio-economic and cultural groups. In cultures where infants are rarely left alone, for example, they may show high levels of distress and anxiety when separated from their mothers. Such a reaction might not be an indicator of insecure attachment as Ainsworth’s theory would suggest, but simply a result of the unfamiliarity of the situation.

Another limitation of Ainsworth’s study is that it cannot be used to determine a general attachment style. As many critics argue, the study only gives an indication of the child’s attachment to the mother. The child may have a different form of attachment to the father or another significant relative. Additionally, studies suggest that attachment styles are not stable and may vary according to the child’s circumstances. A child who appears to be securely attached in one situation may seem insecurely attached in another. Anyone interpreting findings from the strange situation test must therefore be careful about generalizing the results.

Some critics have also taken issue with Ainsworth’s ‘maternal sensitivity hypothesis’ since studies have found only a weak correlation between maternal sensitivity and attachment. They contend that Ainsworth’s theory is overly simplistic since maternal sensitivity cannot adequately account for differences in attachment styles. They believe attachment is best explained by a combination of factors, including the child’s inborn temperament, rather than a single factor as Ainsworth suggests.

Mary Ainsworth's Books, Awards, and Accomplishments

Mary Ainsworth published many articles and several books during her long career. Some of her more popular literary works are listed below:

- Doctor in the Making (1943) - This book recounts the experiences of Mary Salter and Author Ham in counseling medical students at the University of Toronto. It highlights the enormous amount of work medical students are asked to consume and shows what they need to do to perform well in medical school.

- Child Care and the Growth of Love (1965) - In this book Bowlby and Ainsworth emphasize the link between parental relationship and mental health. They also show how children may respond to the temporary or permanent loss of a mother figure.

- Infancy in Uganda (1967) - A classic study of mother-infant attachment that shows how certain behaviors cross cultural, linguistic, and geographic boundaries.

- Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation (1978) - This book presents a method for evaluating the qualitative nature of the mother-infant attachment relationship

Ainsworth was also presented with many awards in recognition of her contributions to the field of psychology. These awards include:

- Distinguished Contribution Award, Maryland Psychological Association (1973)

- Distinguished Scientific Contribution Award, Virginia Psychological Association (1983)

- Distinguished Scientific Contribution Award, Division 12 (Division of Clinical Psychology), American Psychological Association (APA; 1984)

- G. Stanley Hall Award, Division 7 (Division of Developmental Psychology), APA (1984)

- Salmon Lecturer, Salmon Committee on Psychiatry and Mental Hygiene, New York Academy of Medicine (1984)

- William T. Grant Lecturer in Behavioral Pediatrics, Society for Behavioral Pediatrics (1985)

- Award for Distinguished Contributions to Child Development Research, Society for Research in Child Development (1985)

- Award for Distinguished Professional Contribution to Knowledge, APA (1987)

- C. Anderson Aldrich Award in Child Development, American Academy of Pediatrics (1987)

- Distinctive Achievement Award, Virginia Association for Infant Mental Health (1989)

- Honorary Fellowship, Royal College of Psychiatrists (1989)

- Distinguished Scientific Contribution Award, APA (1989)

- Elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1992)

- Distinguished Professional Contribution Award, Division 12 (Division of Clinical Psychology), APA (1994)

- International Society for the Study of Personal Relationships Distinguished Career Award (1996)

- Mentor Award, Division 7 (Division of Developmental Psychology), APA (1998)

- Gold Medal Award for Life Achievement in the Science of Psychology, American Psychological Foundation (APF, 1998)

Personal Life

Despite her intelligence, drive and supportive family background, Mary Ainsworth needed to overcome a number of challenges before she found success in her professional life. For example, she had to cope with international war and its aftereffects. She also had to travel around the world with her former husband to help advance his career. Even so, Ainsworth made the most of her circumstances. She used her time in the military to hone her clinical skills and used Leonard’s frequent travels to meet influential people around the world.

One of the most difficult life changes for Ainsworth to cope with was her divorce from her husband. When her marriage ended, she became so depressed that she needed to seek psychoanalytic therapy for a long time. Interestingly, going to therapy had a positive impact on her career as she became very interested in psychoanalysis.

Another challenge Ainsworth had to overcome was sexism in the workplace. During her time at Johns Hopkins her salary did not match her experience, age, or academic contributions. When three chairmen recommended raising her salary, it did not increase by much. Ainsworth had to write a letter to the Dean before the University decided to pay her a fair wage.

Other instances of sexism at Johns Hopkins arose during the daily lunch break. Until 1968, female faculty members were not allowed to eat in the same lunch room as the male staff. The University suggested this was to prevent the female teachers from seeing the men when they were informally or inappropriately dressed during their lunch break. However, this arrangement greatly reduced the opportunity female teachers had to meet and engage with department heads (who were often male).

In 1975, Mary Ainsworth left Johns Hopkins in order to join the Department of Psychology at the University of Virginia. One of the primary reasons for her move was that several of her friends from Johns Hopkins had also decided to relocate to that university. Ainsworth retired reluctantly at the age of 70. Nevertheless, she continued her own independent research until she was 76 years of age.

As Ainsworth got married relatively late in life, she never had any children. However, she was a very festive woman who enjoyed parties, dancing, and whiskey. Her hobbies included reading murder mysteries, listening to music, playing sports, and playing board games. She also had a liking for silk-covered furniture, oriental carpets, and Herman Maril paintings.

Mary Ainsworth died from a massive stroke on March 21, 1999. She was eighty-five years old. While she does have her fair share of academic critics, it is clear that her work played a major role in our current understanding of child development and inspired much research on early childhood relationships. Today, Mary Ainsworth is fondly remembered as the “Mother of Attachment Theory.”