We show our emotions through our facial expressions. We smile when we are happy and frown when we are angry. This is one of the ways we communicate our feelings to others. But did you know it might also work the other way around? Our facial expressions can influence our emotions.

This is the main assumption of the facial feedback hypothesis.

What Is the Facial Feedback Hypothesis?

The facial feedback hypothesis suggests that contractions of the facial muscles communicate our feelings not only to others but also to ourselves. In other words, our facial movements directly influence our emotional state and our mood even if the circumstances around us don't change!

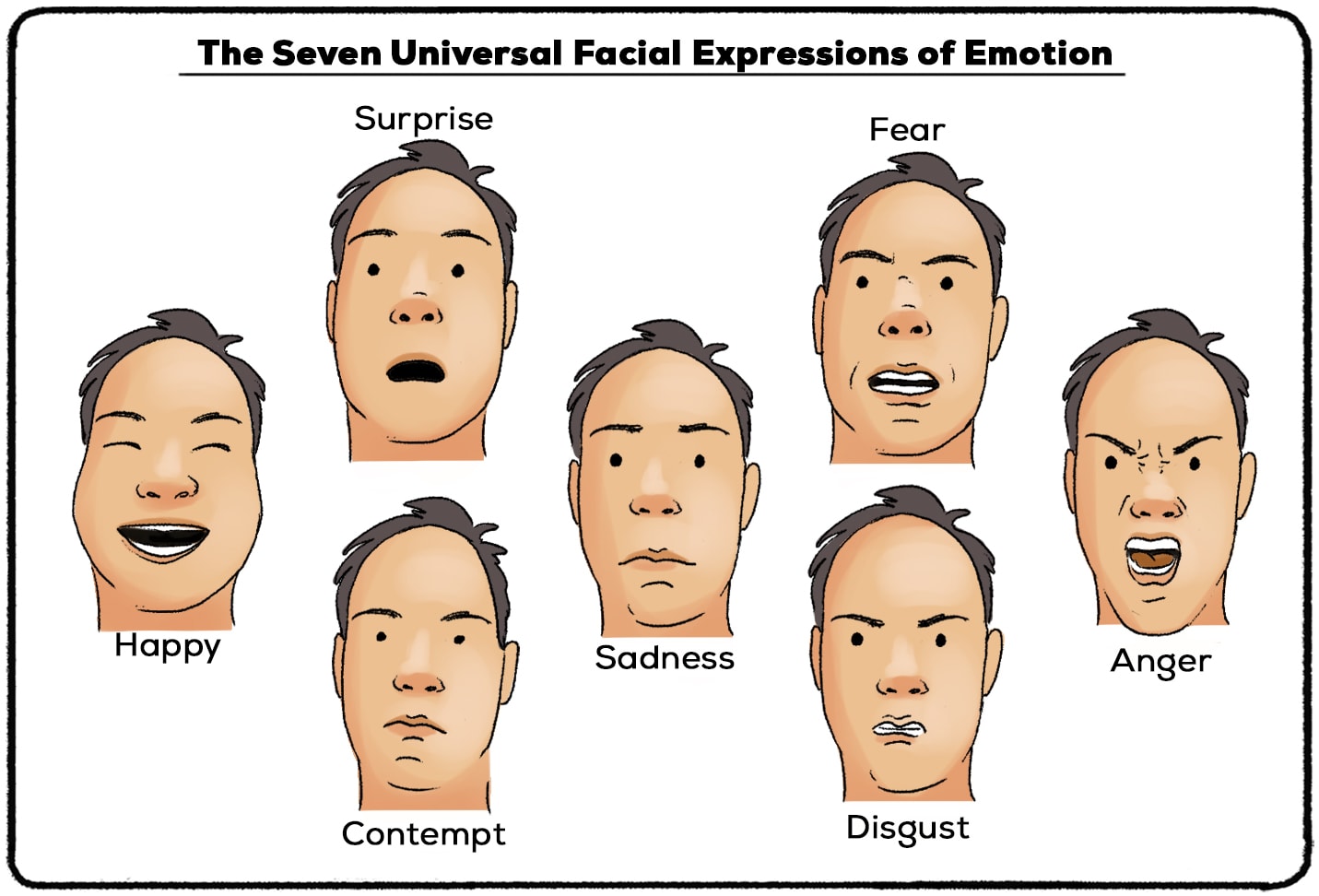

All humans are thought to share seven basic emotions: happiness, surprise, contempt, disgust, sadness, anger, and fear. Each one of these emotions has unique facial expressions associated with it. Raised lip corners and crow’s feet wrinkles around eyes mean joy, while tightened lips and eyebrows pulled down signify contempt.

But facial expressions are more than just representations of our emotions. They contribute to and sustain what we are feeling.

Example of Facial Feedback Hypothesis at Work

The best example of this theory is easy to perform. Go to the mirror and smile. Keep smiling...keep smiling! Even if you were in a bad mood before, you are likely to lighten up and maybe even start laughing! (This is much more fun to try than scowling!)

Who First Wrote About Facial Feedback Hypothesis?

The origins of facial feedback hypothesis can be traced back to the 1870s when Charles Darwin conducted one of the first studies on how we recognize emotion in faces. Darwin suggested that facial expressions of emotions are innate and universal across cultures and societies. In his book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, he argued that all humans and animals show emotion through similar behaviors.

Paul Ekman's Contributions to Facial Feedback Hypothesis

Numerous studies have since confirmed Darwin’s idea that facial expressions are not socially learned. Instead, they appear to be biological in nature. In the 1950s, American psychologist Paul Ekman did extensive research on facial expressions in different cultures. His findings were in line with Darwin’s idea of universality. Even the members of most remote and isolated tribes portrayed basic emotions using the same facial movements as we do.

What’s more, expressing emotions through facial movements is not any different in people who were born blind. Although they can neither see nor imitate others, they still use the same facial expressions to project their emotions as sighted people do.

There are, however, a few exceptions.

People with schizophrenia and individuals on the autism spectrum have not only difficulty recognizing nonverbal expressions of emotions, but also producing these spontaneous expressions themselves. They typically either remain expressionless or have looks that are hard to interpret.

The James-Lange theory of emotion

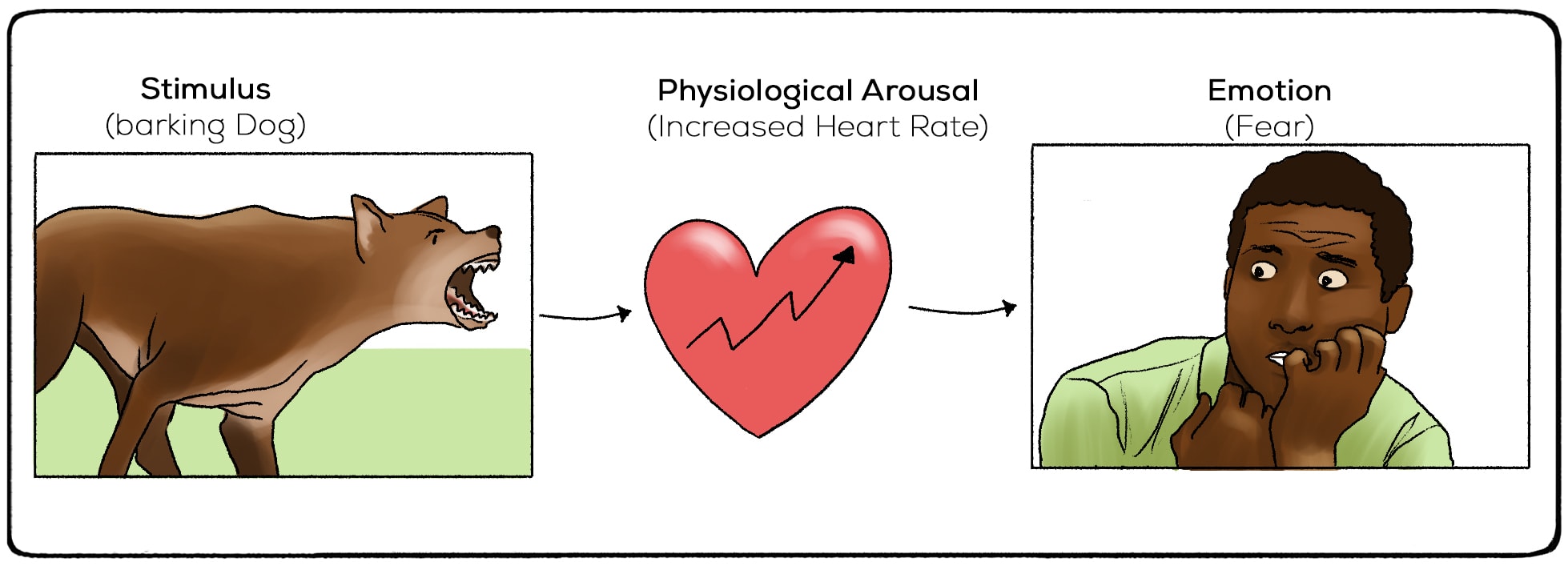

A decade after Darwin’s study, the father of American psychology William James and Danish physiologist Carl Lange proposed a new theory of emotion that has served as a basis for the facial feedback hypothesis. The James-Lange Theory of Emotion implies that our facial expressions and other physiological changes create our emotions.

James famously illustrated this assertion with a story of a man being chased by a bear. A man is unfortunate enough to encounter a bear in a forest. He is afraid and, naturally, his heart races and he is sweating as he starts running away. According to the psychologist, it is precisely these physiological changes that provoke the man’s feeling of fear. In other words, he doesn’t run from the bear because he is afraid. He is afraid because of his physiological response to running away.

Fritz Strack’s cartoon experiment

In 1988, German psychologist Fritz Strack and his colleagues conducted a well-known experiment to demonstrate the facial feedback hypothesis. The participants in Strack’s experiment were instructed to look at cartoons and say how funny they thought these cartoons were. They were asked to do this while holding a pen in their mouths. Some participants held the pen with their lips, which pushed the face into a frown-like expression. Others held it with their teeth, forcing a smile.

Strack’s results were in line with the facial feedback hypothesis and were since confirmed by several other studies. The participants who used a pen to mimic a smile thought that the cartoons were funnier than those who were frowning. The participants’ emotions were clearly influenced by their facial expressions.

Characteristics of Facial Feedback

The brain is hardwired to use the facial muscles in specific ways in order to reflect emotions. When contracted, facial muscles pull on the skin allowing us to produce countless expressions ranging from frowning to smiling, raising an eyebrow, and winking. In fact, we are capable of making thousands of different facial expressions, each one lasting anywhere between 0.5 seconds (microexpressions) to 4 seconds.

But facial expressions can indicate various degrees of emotions as well. When we are slightly angry, we display only a light frown and somewhat furrowed eyebrows. If we are furious, our expression becomes more distinctive. In addition, we can show combinations of different emotions through subtle variations of our facial movements.

The facial feedback hypothesis has the strongest effect when it comes to modulation, that is, intensifying our existing feelings rather than initiating a completely new emotion.

Modulating also means that if we avoid showing our emotions using our facial muscles we will, as a consequence, experience a weaker emotional response. We won’t feel the emotions as strongly as we otherwise would. The lack of facial expressions or inhibition of these expressions lead to the suppression of our emotional states.

Applications of the Facial Feedback Hypothesis

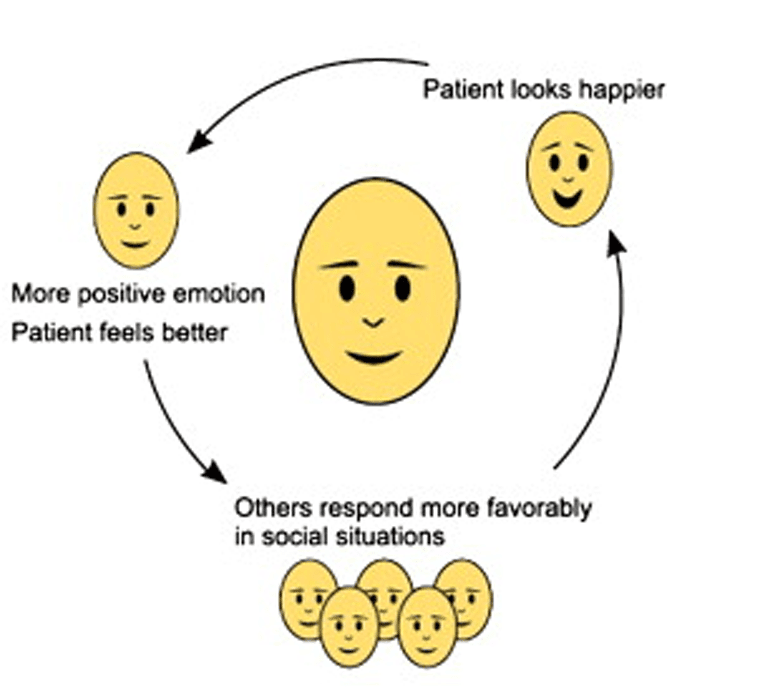

The facial feedback phenomenon has several possible applications. It can help us be more positive, have better control of our emotions, and strengthen our feelings of empathy. We can simply use the facial feedback hypothesis to make us feel better in situations that we would rather avoid. If we force a smile instead of frowning at a boring event, for example, we may actually start to enjoy ourselves a bit more. We can use the same exercise whenever we are feeling overwhelmed, powerless, or stressed.

Research shows that regulating emotions through facial feedback can have positive outcomes in areas ranging from psychotherapy to child education and endurance performances.