If you're interested in the interactions between social psychology, individual identity, politics, history, and culture, you need to learn the name "Erik Erikson."

Who Was Erik Erikson?

Erik Homburger Erikson was a German-born American psychoanalyst, psychologist, professor, and author. He is best known for his theory on psychosocial development and for introducing the concept of an identity crisis. Erikson is one of the most cited psychologists of the 20th century.

Erik Erikson's Birth and Childhood

Erik Erikson was born on June 15, 1902 in Frankfurt am Main, Germany. His mother, Karla Abrahamsen, lived in Copenhagen, Denmark, and came from a well-respected Jewish family. Karla married a Jewish stockbroker named Valdemar Isidor Salomonsen, but their marriage did not last. Karla left Denmark for Germany when became pregnant with Erikson out of wedlock.

Erikson’s father was a non-Jewish Dane, but not much else is known about him. When young Erik was born, his mother gave him the surname “Salomonsen”—the same as her former husband. After giving birth, Karla became a nurse and moved to the German city of Karlsruhe. She married Erik’s pediatrician, Theodor Homburger, in 1905.

In 1908, three years after her second marriage, Karla changed Erik’s surname to “Homburger.” Erik was officially adopted by his stepfather in 1911. His mother and stepfather told him they were his biological parents for most of his childhood. When they finally told Erik the truth, he was very upset and remained bitter about the lie for the rest of his life.

Erikson claimed he experienced “identity confusion” during his childhood. Although he practiced the Jewish religion, the people in his community could see that he looked different from them—he was a tall, fair-haired boy with bright blue eyes. When he went to temple school, the Jewish children teased him for his Nordic heritage. When he went to grammar school, the gentile children teased him for being Jewish.

Young Erik did not feel as if he fit in with either culture. He also did not feel he was fully accepted by his stepfather, who he believed was more attached to his own biological daughters.

Erik Erikson’s Educational Background

Erikson’s high school years were spent at Das Humanistische Gymnasium. His favorite subjects were history, art, and foreign languages. However, Erikson did find school to be very interesting and he graduated without any academic honors. After leaving high school, he decided to enroll in an art school in Munch rather than study medicine as his stepfather wanted.

During his young adulthood, Erikson was unsure about what his career path would be. He was also uncertain about his fit in society, so he decided to go find himself. After dropping out of art school, he took some time off to travel through Germany with his friends. He covered his personal expenses by selling or trading his sketches with people he met on his travels.

After traveling for a while, Erikson came to the conclusion that he did not want to be a full-time artist. So he decided to return home to Karlsruhe and teach art. Erikson was eventually hired by a wealthy woman to sketch and tutor her children. As he did a very good job, he was soon hired by several other families.

Some of the families Erik worked with were friends with Sigmund Freud and his daughter Anna. When Erikson was twenty-five years old, his friend Peter Blos and Anna Freud invited him to Vienna, Austria, to tutor children at the Burlingham-Rosenfeld School. Erik was asked to tutor the students in art, geography, and history. These students had wealthy parents who were undergoing psychoanalysis with Anna Freud at the time.

When Anna observed how well Erik worked with the children in his care, she urged him to enroll at the Vienna Psychoanalytic Institute. Erik enrolled and later specialized in child psychoanalysis. While he was studying psychoanalysis, he also studied the Montesorri Method of education (a child-focused educational approach based on observation). Erikson published his first paper in 1930 and received a diploma from the Institute in 1933.

In 1930, Erik married a Canadian woman named Joan Serson. She was an artist and a dancer at the time. The couple had two young sons while they were living in Vienna. Their names were Kai and Jon.

However, the family did not remain in Vienna for long. In 1933, Hitler rose to power in Germany and Erikson soon heard about the burning of Freud’s books in Berlin. Erikson believe the Nazi sentiment would soon spread to Austria so he and his family fled to Copenhagen, Denmark. When they were unable to gain citizenship in Denmark, they fled to America.

Erikson’s Achievements in America

After Erikson arrived in Boston, he started practicing child psychoanalysis. He was the first child psychoanalyst in the city. He soon joined the faculty at the Harvard Medical School. At Harvard, he became interested in studying the creativity of the ego in mentally stable people.

In 1936, Erikson left Harvard to become a member of the Institute of Human Relations at Yale University. Two years later, he started working with Sioux Indian children in South Dakota and studied the influence of culture on child development. He also worked with the Yurok Indians in northern California. These studies contributed greatly to Erikson’s later theory on psychosocial development.

At roughly the same time he began working with Native American children, Erik and his family received American citizenship. In 1939, he made the decision to change his surname from “Homburger” to “Erikson.” The name change was warmly accepted by his family. His children, in particular, were delighted they would not be called “hamburger” by their friends any longer.

Erikson left Yale in 1939 to move his practice to San Francisco. In 1942, he became a professor of psychology at the University of California, Berkeley. He wrote the essays that were later compiled in Childhood and Society (1950) during the 1940s. This is the work that introduced Erikson’s stages of development to the world.

In 1950, the University of California asked Erikson to sign a loyalty oath. Erikson refused and resigned from his position. After leaving the university, he joined the Austen Riggs Center—a psychiatric treatment facility in Massachusetts. He rejoined the faculty at Harvard in 1960 and remained there until he retired in 1970.

Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development is one of the most popular theories in the field of psychology. Like Sigmund Freud, Erikson believed that personality develops gradually in a series of stages. However, Erikson proposed a larger number of stages than Freud and focused on the social rather than sexual conflicts at each stage. Whereas Freud believed that personality is shaped primarily by early childhood experiences, Erikson suggested that personality development continues across the entire lifespan.

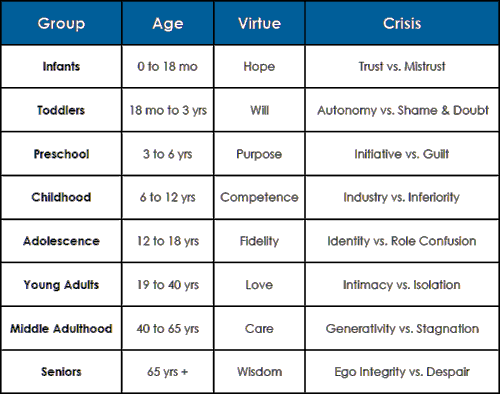

According to Erikson, humans go through eight stages of development. In each stage, there is a psychological conflict or crisis that must be resolved. Each conflict is described in terms of two qualities, one of which is considered desirable, and the other undesirable. A conflict is resolved successfully if by the end of a given stage, the positive quality greatly outweighs the negative one. Erikson believed that each stage builds on the previous one(s) so failure to resolve a conflict will negatively affect personality development in later stages.

Erikson’s eight stages of psychosocial development are as follows:

- Trust vs Mistrust

- Autonomy vs Shame and Doubt

- Intitiative vs Guilt

- Industry vs Inferiority

- Identity vs Role Confusion

- Intimacy vs Isolation

- Generativity vs Stagnation

- Ego Integrity vs Despair

Trust vs Mistrust - The first of Erikson’s stages lasts from birth to one year of age. At this stage in their lives, infants depend on others to provide everything they need, including food, clothing, shelter and security. If caregivers are warm, loving and responsive to the needs of infants, they will learn to trust the adults in their environment. They will come to view the world as a safe, stable place in which they can confidently rely on the people around them. They learn to trust both the people they come in contact with and the environment in which they live.

When caregivers are harsh, unresponsive or inconsistent in caring for the needs of infants, the infants develop feelings of mistrust. They begin to view the world and the people in it as cold, unpredictable and unreliable. Instead of feeling safe and secure in their environment, these infants become fearful and wary of others.

Autonomy vs Shame and Doubt - The second stage of psychosocial development lasts from one to about three years of age. During this stage, children naturally begin to show a level of autonomy or independence. They learn to complete basic tasks such as feeding themselves and begin to express preferences for certain foods, toys, clothes, etc. This is also the stage where they start learning to control their bodily functions through toilet training.

The extent to which children develop the quality of autonomy largely depends on their caregivers. If children are allowed the freedom to make simple choices and complete basic tasks for themselves, they will leave this stage feeling confident in their abilities. If caregivers do not support their efforts to choose and do things for themselves, they will end up feeling ashamed, doubtful and incompetent.

Initiative vs Guilt - During the preschool years (around 3 to 6 years of age), children try to exert greater control over their world by planning, initiating and directing various activities. This is most clearly seen when they socialize and play with each other. Children are more likely to develop initiative when they are given the freedom to play, explore and be adventurous. Of course, parents must be balanced in order to protect young ones from danger. But parents who are over-controlling and restrictive could end up stifling their children’s initiative. Similarly, when parents scold their children for trying things on their own or for making mistakes, these children end up feeling guilty and fearful. In time, they may stop showing initiative completely.

Industry vs Inferiority - This stage of development lasts from about age 6 to 12. During these early school years, Erikson believed the main goal for children is to learn industriousness. This involves trying to learn and master new skills in various aspects of life, such as academics, sports, arts and social skills. Those who excel in one or more areas experience a sense of pride in their accomplishments, especially when they receive praise from others. On the other hand, children who do not work at developing their skills, who receive little or no commendation, and who are regularly criticized by others end up feeling inferior to their peers.

Identity vs Confusion - Between the ages of about 12 and 20, the main task facing individuals is developing a sense of identity. This is often a stage of exploration where adolescents experiment with different roles, beliefs, values and goals in order to find the ones that suit them best. If the conflict is resolved successfully, individuals ends up with a clear sense of who they are and a feeling that they are in control of their life. Failure to resolve the conflict results in insecurity and confusion.

Intimacy vs Isolation - During early adulthood (20-40 years), personal relationships become increasingly important. The main task at this stage is developing close, stable friendships with others, including intimate relationships. For this to occur, Erikson believed that a stable sense of identity is necessary. This means that if the identity crisis in the previous stage is not resolved successfully, individuals will have difficulty achieving intimacy with others. People who master the task at this stage develop long-lasting relationships in which they feel loved and valued. Those who are not successful at this stage have difficulty forming close relationships and may experience feelings of loneliness and emotional isolation.

Generativity vs Stagnation - The seventh stage of development occurs during middle adulthood, approximately 40 to 65 years of age. During this time, individuals are focused on becoming productive members of society. Those who master this task are usually very active at home, on the job and in their communities. They work hard at tasks such as raising a family, building a career and volunteering to help others. They begin to feel as if they are giving back to society and are making valuable contributions to the development of others. This is what Erikson termed generativity.

Those who fail to master the conflict at this stage experience what Erikson called stagnation. Because they are not very involved in social activities and show limited interest in others, they end up feeling disconnected and unproductive.

Integrity vs Despair - During the final years of life (65 years and older), elderly adults tend to reflect on the life they have lived. Those who conclude that they lived a happy, fulfilling and productive life experience deep satisfaction and a sense of integrity. They have few regrets and are at peace with themselves, even in the face of death. Those who are unsuccessful at this stage experience numerous regrets and are dissatisfied with the life they lived. They approach the end of their life with bitterness, fear and despair.

How to Apply Erikson’s Theory to the Classroom and Beyond

Erikson’s theory of development may be applied in a variety of contexts. These include:

- Parenting - Erikson’s theory can help parents understand the social and emotional issues children face at different stages of their life. The theory also suggests ways that parents can foster, rather than hinder, the development of their children.

- Psychotherapy - Erikson’s stages can help therapists understand the developmental issues being faced by their clients and the stage(s) at which they may have become “stuck” in their development.

- Education - Using their knowledge of Erikson’s stages, teachers can tailor their methods of instruction to support students in their efforts to develop qualities such as initiative, industry and a sense of identity. For example, teachers can help children develop industry by carefully assigning tasks that they can complete successfully and by regularly praising their achievements and efforts.

- Healthcare - An understanding of Erikson’s stages can help healthcare providers be more sensitive to the needs of their patients. For example, an elderly patient who always appears to be grouchy may actually be experiencing a sense of despair. A nurse who recognizes this is in a better position to respond with empathy rather than annoyance.

Criticisms and Limitations of Erikson’s Theories

Erikson’s theory of development is valuable in that it helps to explain many of the psychological and social changes that occur across the lifespan. However, like all other theories, it has limitations. One major criticism of Erikson’s theory is that it does not adequately explain what must be done, or the experiences that must be had, to successfully resolve the conflict at each stage. Additionally, although Erikson claims that the outcome of one stage affects development during later stages, he does not say exactly how this happens. Thus, it can be said that while Erikson’s theory outlines what takes place during development, it does not adequately detail how or why such development occurs.

Another criticism of Erikson’s theory is that it does not apply to some cultures and societies. For example, Erikson claims that adolescents develop a sense of identity by exploring and experimenting with various roles, beliefs and relationships. However, in some cultures, decisions regarding such things are largely determined by adults who impose their choices on adolescents. It is common in some societies, for example, for parents to choose their children’s marital partners or to steer them towards certain occupations.

On Reddit, u/adamdoesit addresses this criticism: "To me, one of the most moving things about Erickson's Identity and the Life Cycle is his awareness of 'the vague but pervasive Anglo Saxon ideal' in the US, and the cruel pressures it brings to bear on a young American separated from that ideal by "the color of his skin, the background of his parents, or the cost of his clothes rather than his wish and his will to learn." I do think he aimed to delineate the universally human, but he seems to me painfully aware of the social lens through which he's obliged to observe it."

Critics have also taken issue with the time frame Erikson specified for each conflict to be resolved. For example, Erikson suggested that the issue of trust vs mistrust arises during infancy and must be resolved at that stage. However, some critics argue that individuals do not permanently resolve this issue during infancy but may be faced with this crisis repeatedly during later stages of their life. Likewise, some argue that adolescence is not the only stage during which individuals actively seek to establish a sense of identity.

Erikson’s Accomplishments: Books, Awards, and More

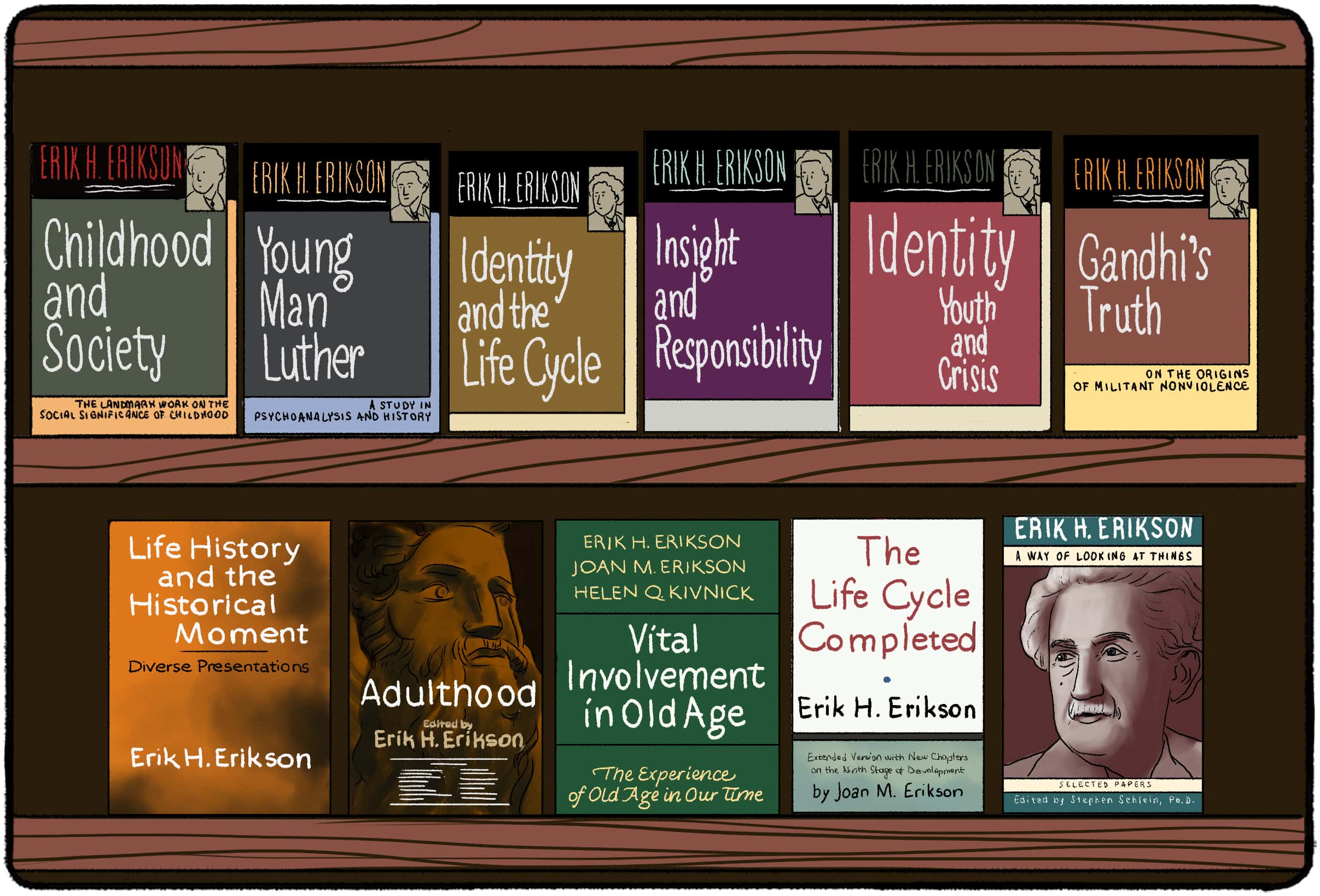

Erikson published several books on his research and theories. Many people believe his most popular book is Childhood and Society (1950), in which he outlined his theory on psychosocial development. His second book Young Man Luther (1958) was one of the first psychobiographies of a well-known historical figure. Erikson won a National Book Award and a Pulitzer Prize for his fifth book entitled Gandhi’s Truth: On the Origins of Militant Nonviolence (1969).

A list of Erikson’s books and significant papers is outlined below:

- Childhood and Society (1950)

- Young Man Luther: A Study in Psychoanalysis and History (1958)

- Identity and the Life Cycle. Selected Papers (1959)

- Insight and Responsibility (1966)

- Identity: Youth and Crisis (1968)

- Gandhi's Truth: On the Origins of Militant Nonviolence (1969)

- Life History and the Historical Moment (1975)

- Adulthood (edited book, 1978)

- Vital Involvement in Old Age (with J. M. Erikson and H. Kivnick, 1986)

- The Life Cycle Completed (with J. M. Erikson, 1987)

- "A Way of Looking at Things – Selected Papers from 1930 to 1980, Erik H. Erikson" ed. by S. Schlein, W. W. Norton & Co, New York, (1995)

In 1973, Erikson was selected for the Jefferson Lecture. According to the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), the Jefferson Lecture is "the highest honor the federal government confers for distinguished intellectual achievement in the humanities." The title of Erikson’s lecture was Dimensions of a New Identity.

Erikson's Family Life and Death

Erik and Joan raised four children together. Kai and Jon were born in Austria, while Sue and Neil were born in America. Although Erik practiced the Jewish religion for most of his early life, the couple converted to Christianity during their marriage.

Erikson’s work had a major influence on his family. His wife Joan often worked closely with him and would edit his research papers. In 1996, Joan suggested a ninth stage of psychosocial development. She was ninety-three years old at the time.

Kai and Sue also followed closely in Erik’s footsteps. Kai is now a respected sociologist and was chosen as the 76th president of the American Sociological Association. Sue is currently a psychoanalyst and psychotherapist who practices in New York City. She specializes in helping people with anxiety, depression, and relationship issues.

Sue has also provided a number of insights on her father. For example, she believes Erik was haunted by feelings of personal inadequacy throughout his life and that his real psychoanalytic identity was not established until he changed his last name from Homburger to Erikson in 1939.

Erik Erikson passed away on May 12, 1994 in Harwich, Massachusetts. He was ninety-one years old. His wife Joan passed away on August 3, 1997 at the age of 94. They are buried together at the First Congregational Church Cemetery in Harwich.