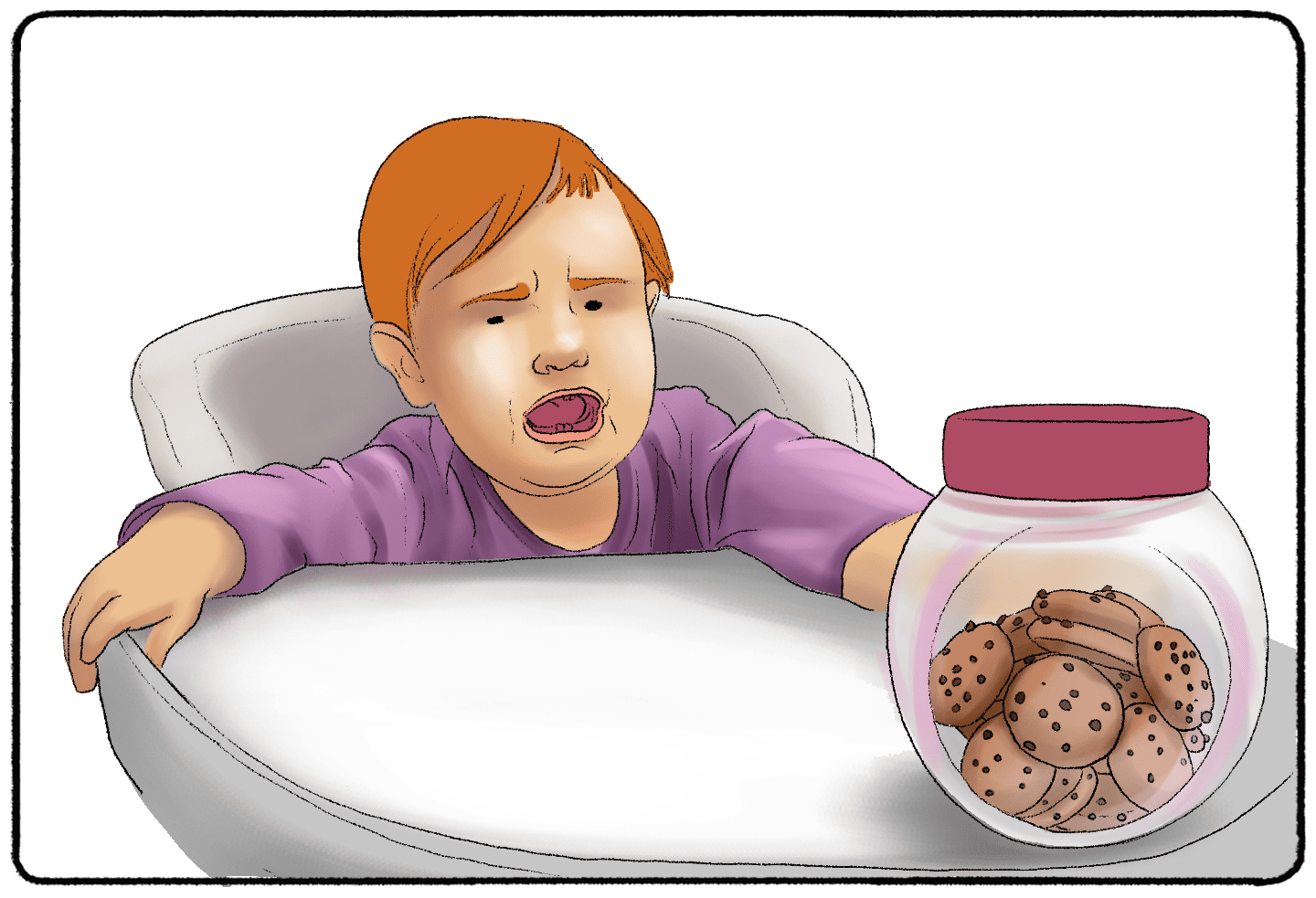

How does a child distinguish between right and wrong? Let’s suppose Tom was told by his parents not to eat any cookies from the cookie jar, but he really wanted to have one. Tom may decide not to take a cookie because he will get into trouble.

What if he is very hungry? Would it still be wrong to have a cookie? Could disobeying the rule be acceptable in this case? The answer may be found in theories like Jean Piaget's Theory of Moral Development.

What Are Piaget’s Stages of Moral Development?

Jean Piaget identified stages of moral development in which a child adheres to rules and makes decisions. Piaget was mainly interested in children’s understanding of moral issues: rules, moral responsibility, and justice. The stages at which children understand rules correlate with cognitive development.

Let's go back to our example of Tom and the cookie jar. For a younger child in the heteronomous morality stage, Tom's decision not to take a cookie might be driven purely by the fear of punishment. In their view, disobeying any rule, irrespective of the reason, is wrong. However, an older child in the autonomous morality stage might weigh Tom's hunger against the rule and see taking the cookie when extremely hungry as a negotiable act, especially if no harm is intended.

What is Moral Development?

Morality is a code of conduct that guides our actions and thoughts based on our background, culture, philosophy, or religious beliefs. Moral development is a gradual change in the understanding of morality.

Children’s ability to distinguish right and wrong is a part of their moral development process. As their understanding and behavior toward others evolve over time, they apply their knowledge to make the right decisions even when it’s inconvenient for them to do so.

Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development

Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget (1896-1980) was among the first to identify how children think inherently differs from how adults do. Unlike many of his predecessors, Piaget didn’t consider children less intelligent versions of adults. They simply have a different way of thinking.

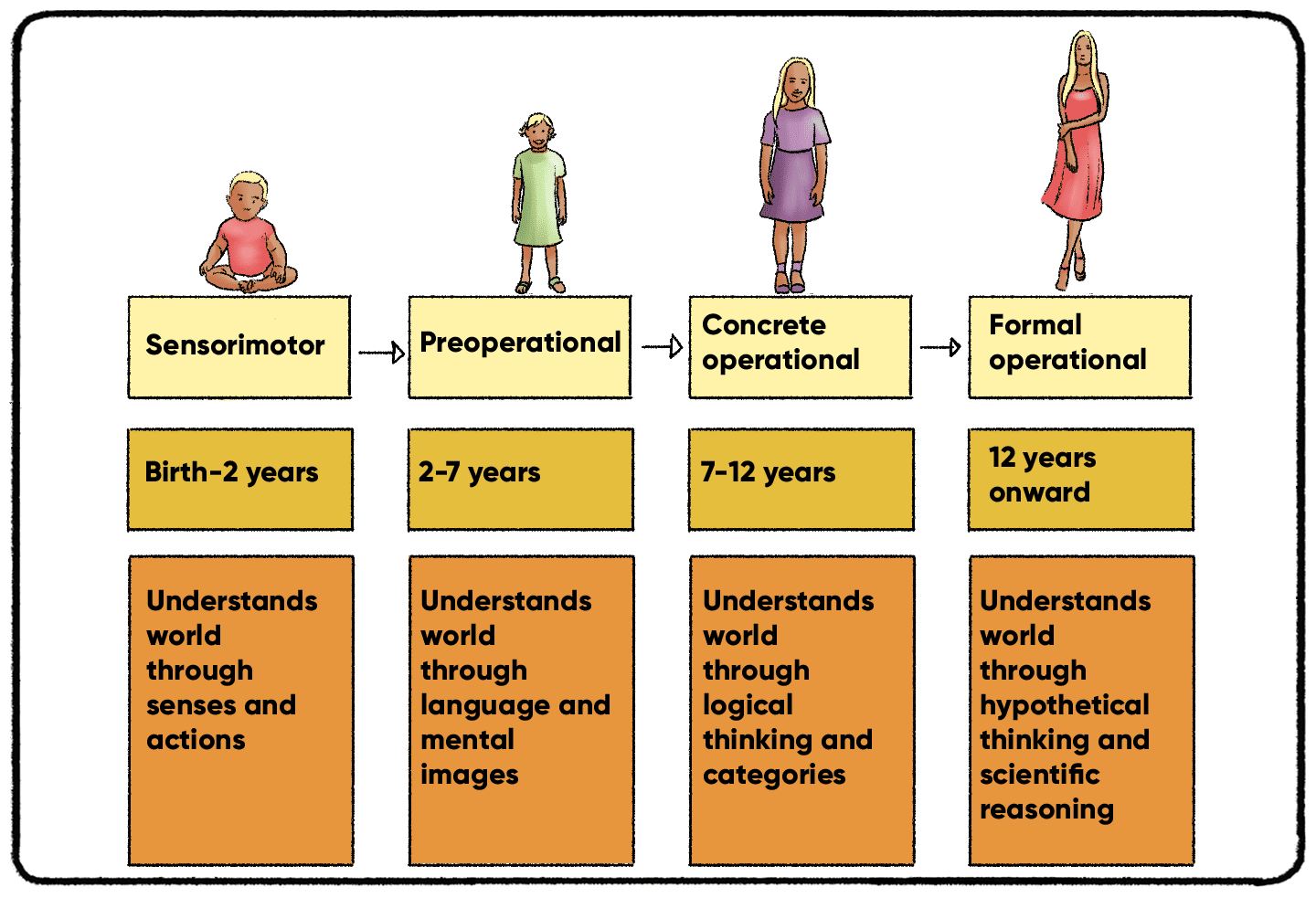

Piaget was the first psychologist to undertake a systematic study of cognitive development. His stage theory of cognitive development explains that children’s mental abilities develop in four stages: sensorimotor, pre-operational, concrete operational, and formal operational. Children can reach their full intellectual potential only after having mastered each one.

For Piaget, children’s moral development is closely related to their cognitive development. In other words, children can only make advanced moral judgments once they become cognitively mature and see things from more than one perspective.

Piaget formulated the cognitive theory of moral development in The Moral Judgment of the Child in 1932. His theory of children’s moral development applies his ideas on cognitive development.

Piaget’s Moral Development Stages

According to Piaget, the basis of children’s reasoning and judgment about rules and punishment changes as they get older. Just as there are universal stages in children’s cognitive development, there are stages in their moral development.

Piaget devised experiments to study children’s perceptions of right and wrong. Part of his research included telling a story about something another child did, like breaking a jar of cookies. Then, he would ask children whether they thought that action was right or wrong. He wanted to know the logic behind their moral reasoning.

He found that while young children were focused on authority, with age, they became increasingly autonomous and able to evaluate actions from a set of independent principles of morality.

Piaget's Theory of Moral Development described two stages of moral development: heteronomous morality and autonomous morality.

Heteronomous morality

The stage of heteronomous morality, also known as moral realism or other-directed morality, is typical of children between the ages of 5 and 10.

Younger children’s thinking is based on the results of their actions and the way these actions affect them. The outcome is more important than the intention. A behavior is judged as good or bad only regarding consequences. There is no room for negotiation or compromise. Eating one cookie from the jar because a child is hungry is just as wrong as stealing all the cookies from the jar by a naughty child. Taking cookies is forbidden and, therefore, always wrong, regardless of the intention.

In middle childhood, children typically believe in the sanctity of rules. An authority figure, such as a parent or teacher, makes rules. These rules must be followed and cannot be changed, they are absolute and unbreakable.

At this stage, children's firm belief that they must follow the rules is based upon their understanding of the consequences. Not following the rules will lead to negative outcomes. Most younger children will obey the rules simply to avoid punishment. Even when completely alone, a child who breaks a rule—takes the forbidden cookie from the cookie jar, for example—will expect to be punished. An authority figure's physical presence is unimportant because morality is imposed from the outside.

But as they develop and mature, children move to a higher level of morality.

Autonomous morality

The stage of autonomous morality, also known as moral relativism or morality of cooperation, is typical of children from the age of 10 and continues through adolescence.

Children are now beginning to overcome the egocentrism of middle childhood. Their appreciation of morality changes due to their newly acquired ability to view situations from other people's perspectives. They are, therefore, also capable of considering rules from someone else’s point of view. Moral rules are not perceived as being absolute anymore. Instead, older children realize that rules are socially agreed-upon guidelines. They are designed to benefit all the group members and are adjustable.

Older children can assess whether a rule is fair or not. Although they still know that it is important to follow the rules, they see them as complex and flexible. They are willing to negotiate and suggest rule modifications. For instance, while playing a board game, older children may want to implement their own rules or change the ones they find unfair.

Piaget believed that the most effective moral learning comes from this group decision-making situation.

As they age, children understand that the motives behind actions are as important as the consequences. Their choice to follow the rules is no longer based on the fear of negative outcomes but on a more complex moral reasoning. During this stage, children recognize that there is no absolute right or wrong and that morality depends on intentions rather than consequences.

How Children Understand the Rules

Another way that Piaget observed children’s morality is by having them play games, including marbles and hide-and-seek. Understanding the rules was critical to the choices made in these games. In addition to general stages of moral development, Piaget created four stages in which the child understood rules:

- Motor Rules

- Egocentric

- Incipient Cooperation

- Genuine Cooperation

These stages correlate with Piaget’s Stages of Cognitive Development.

Motor Rules

While the child is under the age of four, they are in the sensorimotor stage. At this point, they are not grabbing the rules from the game unless they want to explore the feel of the paper. Children in this stage act based on exploring their motor schemes and how they relate to the game objects. Think about a toddler picking up a marble, putting it in their mouth, throwing it across the room - they’re not doing it because it’s in the rules. They just want to explore.

Egocentric

A child is in the preoperational stage between the ages of 4-7. They are largely egocentric, and their understanding of rules is egocentric, too. When a child is egocentric, they make up the rules. For example, a child playing with marbles may decide to place all the marbles in a cup. They may fling the marbles at the cat. However, the game played is largely created by the children themselves.

Incipient Cooperation

From the ages of 7-11, the child is in the concrete operational stage. Children are starting to see the world from a more empathetic point of view. How they interact and communicate with other players, however, varies. Some are cooperative, while others want to play the game their way. Children may sit and listen to the game's rules but might not comprehend or decide to play by them.

Genuine Cooperation

By age 12, when the child is in the formal operational stage, they begin to understand the rules. What’s more, with this understanding comes an adoration for the rules. They start to abide by them and want other children to do the same.

To bring this to life, think about how children approach games. While playing a game of checkers, a younger child might insist on moving a piece in a way that's not allowed by the rules just because they like it. As they grow older, they might start to understand the importance of rules, and by the time they're adolescents, they not only play by the rules but also expect and encourage their peers to do the same.

Criticisms of Piaget's Theory of Moral Development

Piaget’s theory of cognitive development was created after he completed similar studies on boys and girls. He believed there were no differences in their cognitive development: conservation, animism, and object permanence were all part of the process no matter what sex the child was born. Piaget’s theory of moral development was created slightly differently.

While boys played marbles, Piaget gave girls the task of playing a game that resembled “hide and seek.” Researchers note that the two games were not a great comparison: the game of marbles was much more complicated. Following the rules required different conflicts and choices.

What does this mean for Piaget’s assessment of morality in girls vs. boys? Well, researchers to this day are unsure. However, researchers critique his choice of having girls and boys play different games and argue that the playing field should be level before conclusions are made.

Furthermore, it's essential to note the potential cultural biases in Piaget’s conclusions. Different societies may have varying perspectives on morality, which could influence how children within those societies understand and interpret rules and moral decisions.

Applying the Stages of Moral Development: A Guide for Educators and Parents

Understanding the intricacies of moral development stages offers a valuable lens through which educators and parents can view and guide a child's ethical growth. Practical application of this knowledge can aid in fostering a deep-seated sense of morality beyond mere rule-following.

- Contextual Discussions: Use daily events or stories to instigate moral discussions. For instance, if a child is tempted to take a cookie without permission (as in the cookie jar example), engage in a discussion instead of a mere reprimand. Ask questions like, "Why did you want to take the cookie?", "How would others feel if they found out?" or "What could have been a better approach?".

- Role Modeling: Children often emulate adults around them. Demonstrating ethical behavior in daily actions and decisions helps children understand the practical application of moral values. When faced with moral dilemmas, explain the thought process behind your decisions with the child.

- Ethical Storytelling: Use stories, whether from books, movies, or real-life incidents, to discuss moral dilemmas. After a story, ask the child what they would have done in that situation, fostering critical thinking about moral choices.

- Group Decision-Making: Encourage group activities where children set their own rules. This could be during play, projects, or even daily routines. This makes them understand the importance of rules and the responsibility of setting them.

- Ethical Challenges: Present children with hypothetical moral dilemmas tailored to their age and understanding. For example, "What would you do if you found a wallet on the playground?" Discuss the various possible actions and their implications.

- Reinforcing Empathy: Emphasize understanding and feeling the emotions of others. Activities or discussions that put children in another person's shoes can be illuminating. For instance, after a disagreement with a friend, you might ask, "How do you think your friend felt when that happened?"

- Flexibility in Rules: Especially for older children, discuss scenarios where rules might have exceptions, making them understand that while rules are essential, the underlying principle of fairness and justice is even more critical.

- Feedback: When children display moral reasoning, provide feedback. Praise their ethical decisions and guide them gently when they veer off track, explaining the rationale.

- Involve them in Rectifying Mistakes: If a child errs, rather than simply imposing a punishment, involve them in understanding the consequences of their actions and making amends. This could be an apology, a gesture, or another appropriate action.

By adopting these strategies, educators and parents can create environments where moral and ethical growth is organic and deeply rooted in understanding and empathy rather than imposed authority. Over time, this helps develop intrinsically motivated individuals to make moral choices, not just because of external rules but because they believe it's the right thing to do.

Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development

Many psychologists identified stages of development: Freud created stages of psychosexual development, Erikson identified stages of psychosocial development, and Piaget also identified stages of cognitive development. However, more than one notable psychologist identified stages of moral development. Alongside Piaget, Lawrence Kohlberg identified stages of moral development. The two theories differ slightly but face similar criticisms.

Kohlberg vs. Piaget's Theory of Moral Development

Both Piaget and Kohlberg focused on how individuals develop their moral reasoning. While they have fundamental similarities, their approach and the intricacies of their stages differ in various ways.

Foundational Differences

Piaget's approach to moral development was based on the premise of children's interactions with their environment, their understanding of rules, and their evolving perspectives of justice. He was particularly interested in how a child's view of their place in the world shaped their morality and decisions. On the other hand, Kohlberg was more focused on moral reasoning itself. He aimed to uncover how and why children and adults deemed certain actions right or wrong.

For a practical context, let's take the scenario of a child faced with the choice to steal a toy from another child. Using Piaget's theory, a younger child in the heteronomous stage might decide against stealing purely because of the fear of punishment or because "it's a rule." On the other hand, Kohlberg's theory might interpret the child's decision based on the reason behind it. If the child avoids stealing due to a universal principle of fairness and rights, they might be operating at one of Kohlberg's higher stages of moral development.

Depth and Breadth

Kohlberg’s model goes further than Piaget's, extending into adulthood. While Piaget identified two main stages of moral development, Kohlberg detailed six stages, further categorized into three levels. Moreover, Kohlberg's stages are more explicit in describing the progression of moral reasoning from a self-centered perspective to a principled, universalistic one.

Integration of Other Theories

Kohlberg incorporated concepts from Piaget’s stages but also integrated ideas from Freud and other developmental psychologists, making his model a synthesis of various psychological viewpoints.

Consider an adolescent deciding whether or not to cheat on a test. Using Piaget's theory, the decision might be based on an autonomous understanding that rules can be flexible, but cheating disrupts fairness. In Kohlberg's theory, if the adolescent decides not to cheat based on a personal principle that honesty is universally right, they would be operating at a higher level of moral reasoning.

Gender Biases and Criticisms

Both theories have faced criticism over the years, especially regarding gender representation. While Piaget's research involved both boys and girls, his choice of games for each gender raised questions about the comparability of the moral challenges presented. On the other hand, Kohlberg faced criticism for only studying boys, which many argue gives an incomplete picture of moral development. This gender bias has led to concerns about the universality and applicability of their conclusions.