Trying to learn how to memorize classical conditioning concepts for your high school or college psychology class? This page is meant to be a resource to help you achieve that goal!

The idea of Pavlov’s dog pops up everywhere in pop culture. It appears in puns. If you ever had to study Brave New World in school, you might have heard references to Pavlov’s work come up in conversation. But can you explain the significance of Pavlov’s dogs and the concept they brought to light? Let's learn about classical conditioning.

What is Classical Conditioning?

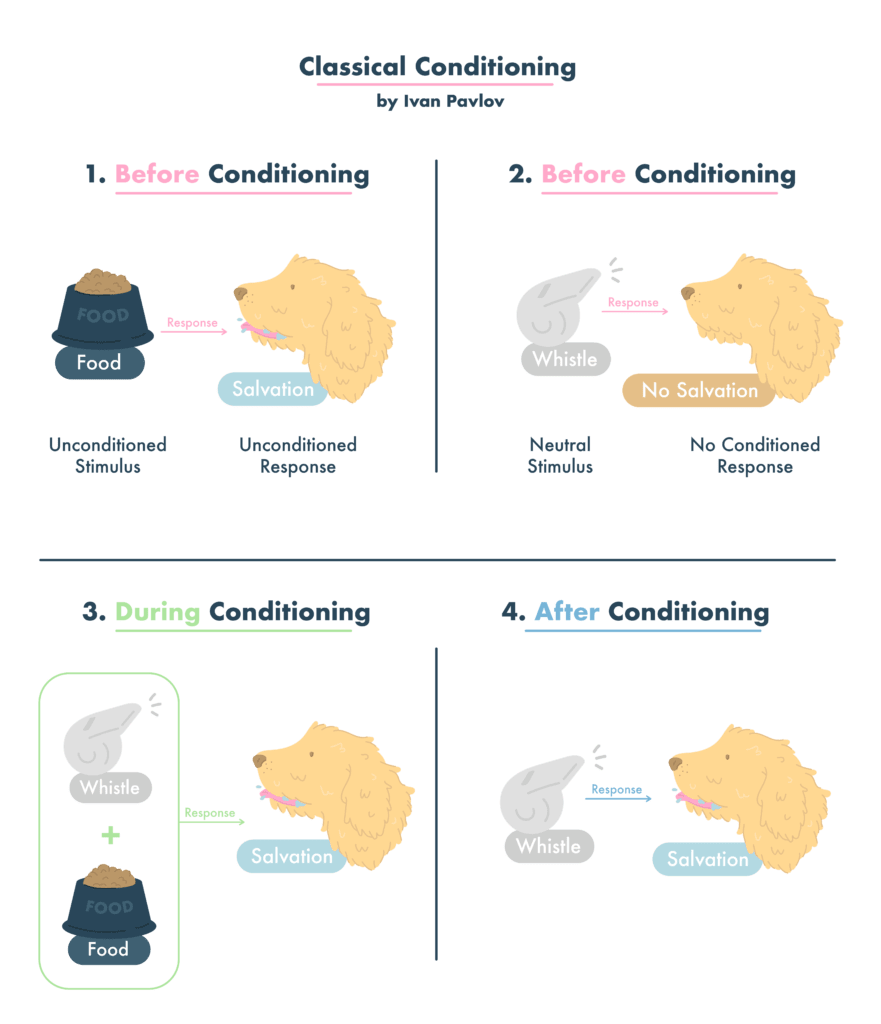

Classical Conditioning is a method of learning that happens when two stimuli are paired together. In many cases, a biological stimulus is usually paired with a neutral stimulus. For the example below, Ivan Pavlov trains dogs to associate the sound of a ringing bell with salivating.

Pavlov’s Dog Study

Behaviorists believe that learned behavior comes from one of two processes: operant conditioning and classical conditioning. In this video, we will focus primarily on classical conditioning.

The idea of classical conditioning was first discovered through the work of Ivan Pavlov, a Russian psychologist. The participants in the study were dogs. Pavlov would ring a bell and then give the dog a treat. This process was repeated over and over again.

Things got interesting when the dogs started to “expect” the treat. They would start salivating at the sound of the bell in anticipation of the treat. Now, the important thing to note is that Pavlov was not trying to train the dogs to salivate. But this response came about through classical conditioning.

How Does Classical Conditioning Work?

To understand classical conditioning, you must understand each component of Pavlov's dog study and how they influenced the dog’s response to salivation. Again, the researchers were not intending to teach the dogs to salivate on command. The salivation was an unconditioned response. The unconditioned response is a naturally occurring response.

Stimuli - Neutral, Conditioned, and Unconditioned

The dogs began to salivate when they heard a bell. Before any studies began, the bell was a neutral stimulus. A neutral stimulus is any stimulus that has no associated response before training. It elicited no response from the dogs. The stimulus became conditioned only after the dogs were exposed to food after hearing a bell. The dogs were conditioned to salivate when they saw the bell, a previously neutral item with a neutral sound. A conditioned stimulus is any stimulus that has been associated with a response.

The food also plays a role - it’s the unconditioned stimulus. An unconditioned stimulus is any stimulus that still creates a response but not the one we manipulate. Taking food out of the equation and into another situation will still cause a reaction in the participants. Seeing the food will make the dogs salivate, whether or not any “learning” has occurred.

There is another term that you should know relating to classical conditioning. It’s a conditioned response. The conditioned response is the response to the neutral stimulus associated with the unconditioned stimulus. I will use another example to show how people or animals can develop conditioned responses to stimuli.

Example of Conditioned Response to Neutral Stimuli

Let’s say you go to the doctor’s office for a vaccine. Before the doctor gives you the painful shot, she touches you with a cotton ball to clean the area. When you get the vaccine, you feel pain and wince.

The next time you visit the doctor, they clean the area with a cotton ball. You jerk your arm away to avoid the vaccine's pain, even though the doctor has not given you the vaccine yet.

That response, jerking your arm away, is the conditioned response. It’s a way of avoiding unconditioned stimuli (the vaccine) and the naturally occurring unconditioned response (pain) caused by the vaccine.

Examples of Classical Conditioning in Everyday Life

In Pop Culture

Classical conditioning works on humans, but we often see cases when people try to “train” others in movies or TV shows. In "The Office," Jim offering Dwight mints whenever he hears an email notification is an example of classical conditioning.

In Parenting

If you are a parent, you might have noticed that your child has developed responses through classical conditioning, whether that was your intention. A child may get excited to attend church in the morning if they know they are getting fast food afterward. If you try to hide a toothbrush or anything they don't like behind your back, they might get nervous whenever they see you holding something behind your back. Fortunately, with humans, you can eventually reason with them and explain why or why not you may be performing a behavior that elicits a conditioned response.

In School

Teachers may use classical conditioning to help students escape their shells or perform tasks they normally wouldn't perform. If a class of students does not like to stand up and present, the teacher could create an environment where that task is rewarded, and the child becomes more comfortable standing up in front of the class.

In Dog Training

On the DogTraining subreddit, you can find plenty of examples of classical and operant conditioning! Check out this post from u/UselessBunch:

"Basic info: two rescue dogs, had them a couple years now, one was a street dog and is very skeptical about being manhandled or contained. Patience and treats have been key.

Now, to start, every time we walk, we sit down after in the doorway and wipe their paws. This serves two purposes: 1) clean paws = clean house, and 2) both pups are now totally desensitized to having their paws handled. It helps that the skeptical dog absolutely adores the taste of the lotion we use on their paws (it's strongly lanolin based). We have to keep him away from the bottle!

What we added to that routine: buzz the grinder, they get a treat. Repeat a few times every paw wipe for most of a week. Slowly introduce it to the claws; they got a treat every buzz, regardless of contact, but when they let me actually buzz the claws for like a microsecond they got huge praise and a handful of treats (it's just kibble, but don't tell them that.)

We went at their pace. We were firm that we wanted them to do this, but we didn't force the issue; especially at first, we let them opt out.

The skeptical boy was not a fan of the buzz buzz, but the treat motivated hound learned fast. So I let her get more treats than him. This made him unbearably curious. Today I had to take turns buzzing claws and I had to call an end, because they were perfectly willing to keep going!"

John Watson’s perspective

At the same time that Pavlov was conducting his studies, Americans were also working to discover similar ideas. In fact, an American psychologist named Edwin Twitmyer conducted a similar study to Pavlov three years earlier than Pavlov. He sounded a bell and would tap a part of the patient’s knee shortly after to test their reflexes. After some time, the sound of the bell would result in a “knee-jerk” reaction.

Twitmyer did not receive credit for his work like Pavlov. However, one American psychologist made a big name for himself due to his work on classical conditioning and behaviorism. His name is John B. Watson.

Little Albert Study

Watson also conducted a study on behaviorism: the Little Albert Study.

This study is famous for being crucial to the behaviorist movement - but also because it’s very dark. Watson used a nine-month-old baby, whom he nicknamed “Little Albert” or “Baby Albert,” to see if fear was an innate trait or something that was learned. He surrounded Albert with various objects, including a white rat, a monkey, a Santa Claus mask, etc. Albert didn’t seem scared of the stimuli, even the white rat.

Here’s where things get uncomfortable. Watson exposed Albert to one of the stimuli. He then banged a steel bar and a hammer - right behind Albert’s head - when the baby would touch the stimulus. Obviously, that sound terrified Albert. He feared the rat and other stimuli associated with the bar and hammer sound. Whenever the stimuli would come near him, he would try to crawl away and start crying.

Let’s check in for a moment here. Do you remember the terms associated with classical conditioning?

The white rat is...now a conditioned stimulus. Formerly, it was a neutral stimulus that did not provoke a response.

The steel bar and hammer are… unconditioned stimuli.

When Little Albert cried, he displayed an unconditioned response. His attempts to crawl away upon seeing the white rat after conditioning were...a conditioned response.

Good work!

Behaviorism

Behaviorism has laid the groundwork for several contemporary therapeutic techniques. Among the pioneers in the field, Mary Cover Jones stands out for her groundbreaking work and for being dubbed the "Mother of Behavior Therapy." Her interest in behavioral interventions was piqued after attending a lecture by John B. Watson, and she was inspired to explore the potential of reversing the negative outcomes of classical conditioning.

Jones' most notable experiment involved a child named Peter, who harbored a deep-seated fear of furry animals. Utilizing a method she coined as "counter-conditioning," Jones introduced Peter to a rabbit, initially from a distance, and gradually brought it closer, all while ensuring the child remained calm and relaxed. During these sessions, Peter was also exposed to other children who demonstrated no fear of the rabbit, reinforcing a positive and fearless association. Over time, Peter's fear diminished, demonstrating the efficacy of Jones' method.

This systematic desensitization approach pioneered by Jones laid foundational principles for modern-day exposure therapies, showcasing her significant contribution to therapeutic techniques and the broader field of psychology.

Can You Use Classical Conditioning On Yourself?

Can you condition yourself? Can you quit smoking, concentrate on your studies, or train yourself to save money by ringing bells?

Yes and no. It is possible to condition yourself to form certain habits, but you must be patient and committed to the idea. There is more to learning than behaviorism.

Cognitive processes play a big role in how you choose to behave and how your brain processes information that it learns. But I’m not telling you you can’t form (or break) a habit with classical conditioning. Give it a go! The more you are determined to form that habit, using classical conditioning or not, the more likely you will start to embody that habit.