Ever jumped because of a sudden loud noise? Or felt your mouth water when you smell your favorite food cooking? These reactions aren't just random; they're part of something called the "Stimulus Response Theory." In simple terms, it's the idea that we react in specific ways to certain things or events around us. Think of it like a cause and effect: something happens (the stimulus), and we respond in a certain way.

This theory helps explain why we do many of the things we do without even thinking about them. It's like our body's automatic reply to the world around us. Some of these reactions are natural, like flinching from a hot stove, while others can be learned over time, like feeling excited when you hear a specific song because it reminds you of a fun memory.

In this article, we'll dive into the fascinating world of stimulus and response, exploring how and why we react to things the way we do. It's a journey into understanding our automatic behaviors a bit better. Ready to discover more about yourself and the world around you? Let's go!

What Is Thorndike's Stimulus Response Theory of Learning?

Stimulus Response Theory was proposed by Edward Thorndike, who believed that learning boils down to two things: stimulus, and response. In Pavlov’s famous experiment, the “stimulus” was food, and the “response” was salivation. He believed that all learning depended on the strength of the relationship between the stimulus and the response.

If that relationship was strong, the response was likely to occur when the stimulus was presented. In order to elicit a specific response to a specific stimulus, you had to strengthen its relationship in one of a few ways. This is where Pavlov’s experiment comes in.

When you think of behaviorism, you may think of Pavlov’s dog. This experiment is one of the most famous experiments in the history of psychology. It is also some of the strongest evidence for theories that fall under the larger category of Stimulus Response (S-R) Theory. Stimulus Response Theories attempts to explain the ways that human beings behave. These theories, and behaviorism as a whole, are not the forefront of modern psychology. Still, they still serve as an important lesson about why we believe the things we believe about decision-making, behavior, and human nature.

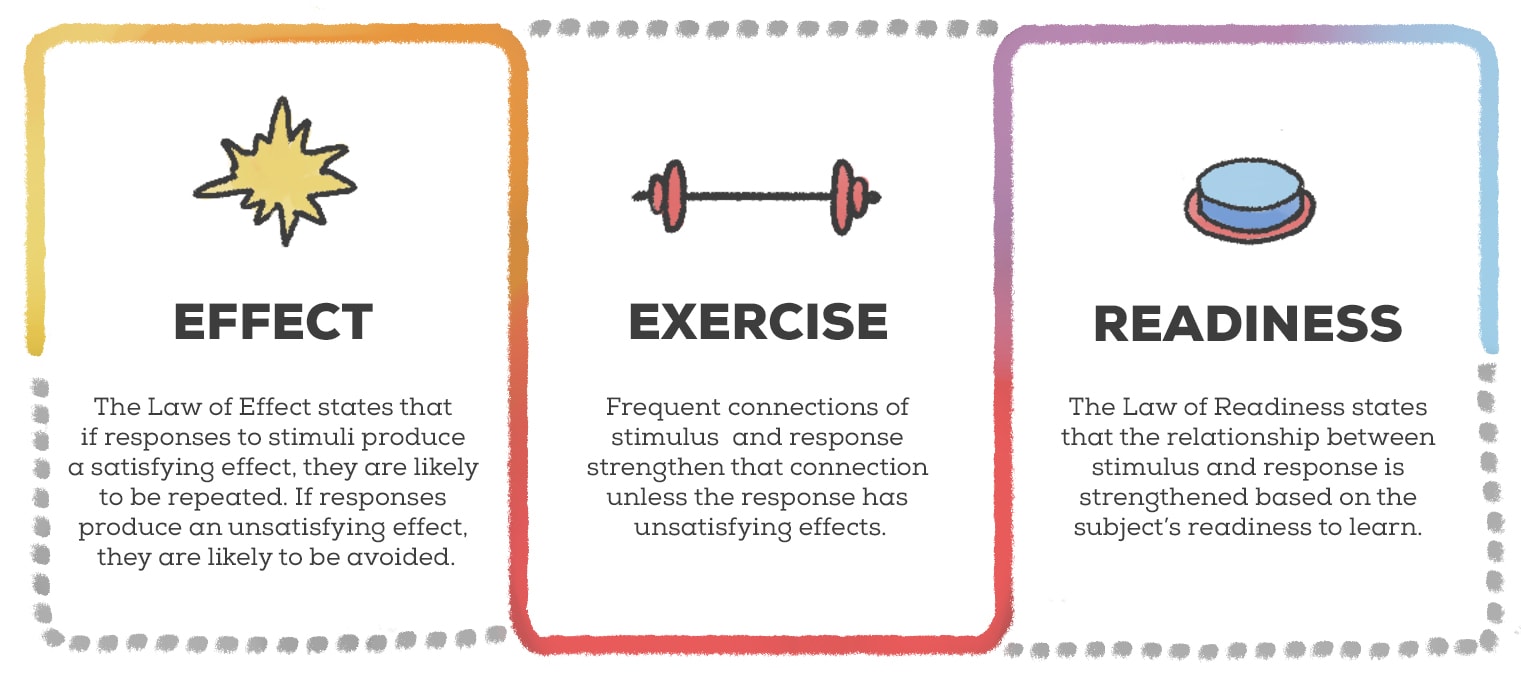

Let’s look at three concepts that Thorndike developed while explaining the Stimulus-Response Theory of Learning: Law of Effect, Law of Exercise, and Law of Readiness.

Law of Effect

Before Pavlov worked with dogs, Thorndike worked with cats.

He would place them in a box. Outside the box was a scrap of fish. As the cats looked for ways to get to the fish, they would try to escape the box. Escaping was as easy as pulling a lever. When the cat pulled the lever, they were able to leave and enjoy the fish.

Thorndike observed the cats be placed in this box over and over again, under the same conditions. He saw that the time it took to pull the lever decreased as the cats associated the lever with the fish. This helped him develop the Law of Effect.

The Law of Effect states that if responses to stimuli produce a satisfying effect, they are likely to be repeated. If responses produce an unsatisfying effect, they are likely to be avoided. The cats enjoyed the scrap of fish that they could access by pulling the lever. If an angry dog replaced the scrap of fish, The Law of Effect states that those cats would not be pulling any levers.

We seek responses with positive effects, strengthening the relationship between a stimulus and the response.

Law of Exercise

The Law of Exercise is an element within Thorndike’s work that he later modified. Initially, Thorndike believed that frequent connections of stimulus and response strengthened that connection. The more often a cat was given the opportunity to pull a lever and receive a fish, for example, the stronger that connection would be and the more likely they would pull the lever.

But, as Thorndike continued his work, he realized that this was not necessarily true. If the response leads to an unsatisfying effect or punishment, the connection between the stimulus and the response will not be strengthened. But Thorndike observed that the connection may not be weakened every time the subject gets “punished,” either.

Law of Readiness

Being subject to continuous trials of pulling levers and escaping boxes sounds exhausting. If a cat, human, or any other creature is too tired to try something out, they might just take a cat nap and leave the response hanging. This idea fits into Thorndike’s law of readiness.

The Law of Readiness states that the relationship between stimulus and response is strengthened based on the subject’s readiness to learn. If the subject, be it a cat or a person, is not interested or ready to learn, they will not connect stimulus and response as strongly as someone who is eager and excited.

These three laws set the foundation for many other theories within behaviorism. Later behaviorists, including B.F. Skinner, Edwin Guthrie, and Ivan Pavlov, have proposed theories that relate to, or are inspired by, the work of Edward Thorndike.

Examples Of Stimulus Response Theory

- Loud Noise - Jumping or covering ears in response.

- Bright Light - Squinting or shutting eyes.

- Touching a Hot Surface - Quickly pulling your hand away.

- Smelling Food - Stomach growling or mouth watering.

- Tasting Something Sour - Puckering lips or wincing.

- Seeing a Scary Image - Gasping or feeling your heart rate increase.

- Hearing a Familiar Ringtone - Reaching for your phone.

- Feeling a Raindrop - Looking up or opening an umbrella.

- Stepping on Something Sharp - Lifting foot and expressing pain.

- Hearing a Fire Alarm - Looking for an exit or evacuating the building.

- Seeing a Cute Animal - Smiling or expressing delight.

- Listening to a Sad Song - Feeling melancholic or tearing up.

- Being in a Cold Room - Shivering or hugging oneself.

- Seeing a Familiar Face in a Crowd - Waving or calling out to them.

- Hearing a Joke - Laughing or smiling.

- Feeling a Bug on Your Skin - Slapping or brushing it away.

- Seeing Traffic Lights Turn Red - Stopping your car.

- Hearing a Doorbell - Going to answer the door.

- Tasting Something Bitter - Spitting it out or expressing dislike.

- Feeling Sand in Your Shoes - Stopping to shake it out.

- Hearing Your Name Called - Turning towards the source or responding.

- Seeing a "Wet Floor" Sign - Walking around the area or treading carefully.

- Smelling Smoke - Searching for the source or alerting others.

- Feeling a Vibration in Your Pocket - Checking your phone.

- Hearing a Baby Cry - Looking for the baby or feeling a sense of concern.

Other Stimulus Response Theories

Contiguity Theory

One such theory includes Edwin Guthrie’s Contiguity Theory. Like other Behaviorists, Guthrie believed that learning occurred when connections were made between a stimulus and a response. But his ideas went beyond exercise and readiness. The Contiguity Theory included the law of contiguity, which suggested that time played a factor in the strength between a stimulus and a response.

If the response did not occur immediately after the stimulus, the subject would be less likely to associate the stimulus with the response. If you get a stomachache in the evening, you might associate your body’s response with what you ate in the morning, but you are much more likely to associate the response with what you ate for lunch or dinner. Time makes a difference.

Drive-Reduction Theory

Another theory that falls under the stimulus-response umbrella is Hull’s Drive-Reduction Theory. Developed in the 40s and 50s by Clark Hull and later Kenneth Spence, this theory looked to “zoom out” on behaviorism and explain the drive behind all human behavior. A stimulus and response are still crucial to this drive.

Drive, Hull and Spence said, is a state that humans experience when they have a need to fulfill. If you are hungry, you are in a state of drive. If you are craving sex, comfort, or safety, you are in a state of drive. As humans, we want to reduce drive and return to a state of calm homeostasis.

What do you do when you are hungry? You eat food and feel full. Drive-Reduction Theory states that when the effect of a response is a reduction in drive, a subject will more likely respond to that stimulus in the same way.

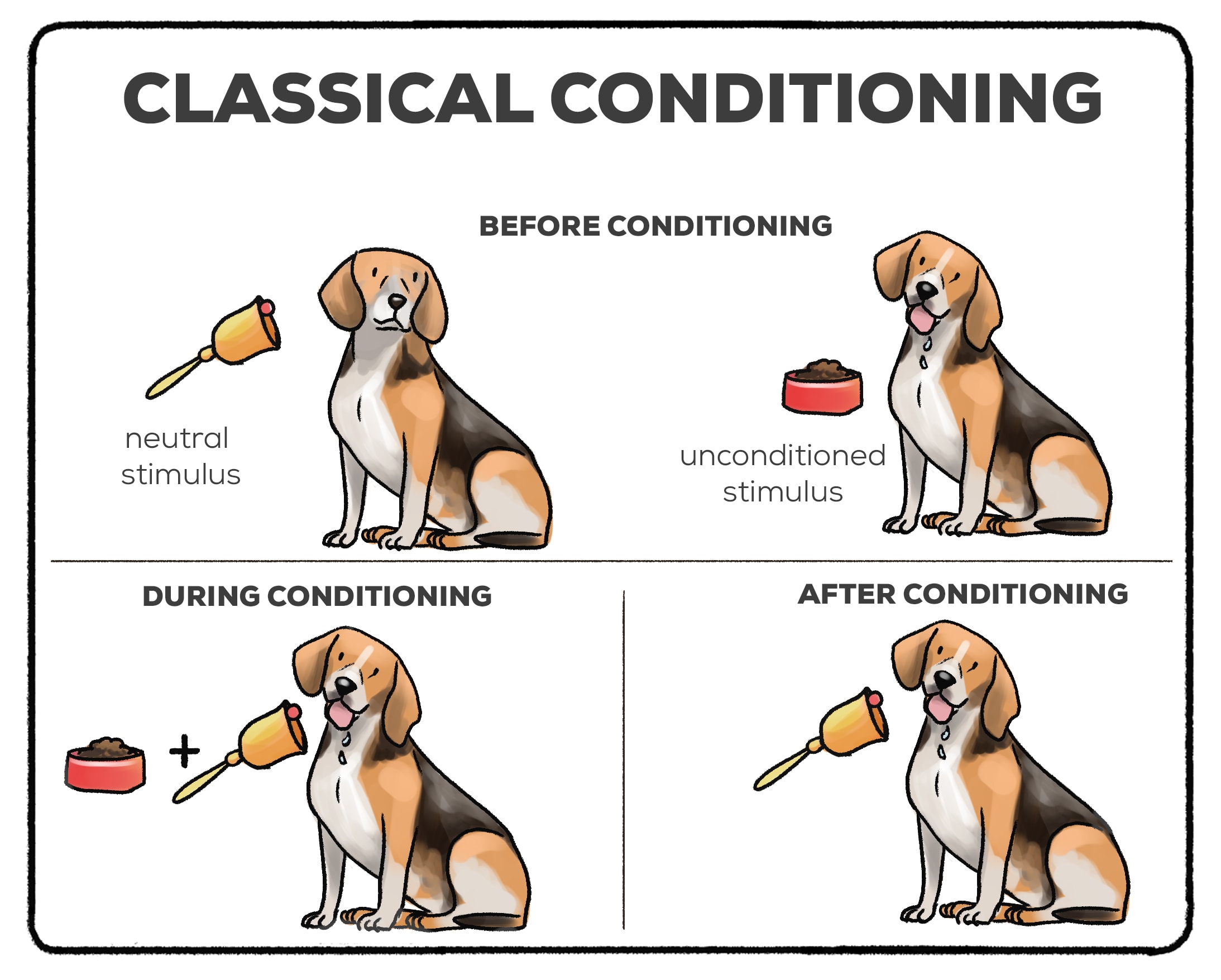

Classical Conditioning

We could not wrap up these theories without talking about Pavlov’s dogs. Pavlov used stimulus-response theory to demonstrate how dogs (or humans) could learn through classical conditioning. This is a process in which a “neutral” stimulus becomes connected to a stimulus that already elicits a response. Once this connection is made, the previously neutral stimulus elicits a response.

Cognitive Psychology

Stimulus response theories, to be blunt, can be quite simple. They are also deterministic in nature. No one wants to believe that their decisions are the result of any sort of conditioning. Additional factors, like your thought process or the experiences that have shaped you as a person, may also influence the decisions you make. Making a decision or performing a behavior often seems more complicated than just responding to the stimulus in front of you.

Although behaviorism and stimulus response theory were the focus of psychology for decades, they were subject to criticism from many experts in the field. Were all actions driven by the unconscious, or did the conscious mind do more than we were giving it credit for? Is human behavior and decision-making more complex than just responding to a stimulus?

As these questions were raised more and more frequently, schools of thought like humanism, positive psychology, and cognitive psychology were born.

These schools of thought are not immune to criticism, either. So completely replacing education on behaviorism with information on cognitive psychology is not necessarily the best approach. Although psychologists view behavior as more than just a stimulus and a response, we cannot forget the theories that built the foundation to what we know today.

Can You Train Yourself?

Teachers are not solely relying on conditioning or behaviorism to teach their students. But, you can still use concepts from stimulus-response theory to teach yourself new behaviors. Want to make your bed every morning? Want to add 15 minutes of meditation into your routine? Maybe you want to replace having a cigarette with seltzer water or a piece of gum. Tap into the laws within the stimulus-response theory to “condition yourself” and bring new behaviors into your routine.

Readiness: Commit to Learning a New Behavior

Ready to learn new behavior? Great. The Law of Readiness states that you will build a stronger connection between stimulus and response. Commit to your readiness by writing down your goals. This could be as simple as writing, “I’m going to quit smoking,” or “I’m going to make my bed every morning.” If you want to go further, write down why learning or unlearning this behavior is important. Writing this down is not going to magically add a behavior to your routine, but it will motivate you in times when you may be tempted to skip the behavior.

Effect: Find a Suitable “Reward”

What satisfying effects can you gain from performing a behavior? For many, the Law of Effect encourages people to reward themselves. This is certainly what behaviorists had in mind when they put together schedules of reinforcement for conditioning.

Let’s say you want to get into running. The first time you run, you feel absolutely great. You’re more likely to run again! If you run with no satisfying effects, you are unlikely to run again unless you put a reward system in place. Maybe you allow yourself to spend an extra hour watching TV, or you wait to listen to that podcast until you go for a run. Whatever reward enhances the results of your behavior (without setting you back from the goals that the behavior is meant to achieve) will make a great motivation to continue performing the behavior.

Exercise: Keep Going!

The stimulus (running) and the response (a podcast) work well together. Now, you just have to keep going! The more you run and save your podcasts for that run, the more likely it will be that you integrate running into your routine permanently. Remind yourself that routines are not built in a day. Sometimes, you will slip up. All of this is okay. Every time you perform the desired behavior, you are contributing to this habit.

There are many approaches that you can use to form habits. Whether you want to build wealth, protect your health, or find happiness in the small moments, stimulus-response theory can help you build habits (or explain how you developed the ones you have!)