The ability to learn is one of the main functions that make us human. Imagine what would happen if we couldn't learn from our or others' mistakes. This unique ability has puzzled cognitive psychologists for decades. We have a pretty good idea of how learning works, but we still have a few holes to figure out.

What is Learning?

The definition used by most psychologists is that learning is the ability to use memory from experiences to change behavior in a permanent manner that benefits the learner.

In behavioral psychology, there are 3 main methods of learning:

- Classical Conditioning

- Operant Conditioning

- Observational Learning

Throughout this article, I'll attempt to give the best-summarized version of each, including a few more lesser-known methods. If you want an in-depth guide of the main three, click the header links.

Classical Conditioning

One of the most famous experiments in cognitive psychology on learning is Pavlov's Dog Experiment. In short, Ivan Pavlov trained (or rather, conditioned) his dogs to salivate when they heard a bell rang, expecting food was next.

In short, we take an "unconditioned response," like salivating to food, and pair it with a "conditioned response" like a bell. Using a "conditioned stimulus" like a bell, we can pair the connections of these responses in the dogs to produce classical conditioning.

John B. Watson was another psychologist interested in classical conditioning but used children as his participants. In his infamous Little Albert Study, Watson conditioned a young boy to be afraid of a white rat. To do so, Watson directed his assistants to bang a piece of metal with a hammer next to Albert's head. It wasn't long before Albert was scared of the white rat - he would whine and cry when he saw one. The problem is that he also seemed afraid of other white things and small rodents.

Classical conditioning pairs two responses together using two unrelated stimuli.

Operant Conditioning

B.F. Skinner is the psychologist famous for conducting experiments that helped theorize his "operant conditioning." In operant conditioning, we can increase or decrease certain behaviors by adding or removing stimuli.

- Positive reinforcement is adding a stimulus to increase behavior.

- Negative reinforcement is adding a stimulus to decrease behavior.

- Positive punishment is removing a stimulus to increase behavior.

- Negative punishment is removing a stimulus to decrease behavior.

You can learn more about Skinner's box and reinforcement schedules on the main page, but let's skip to the third primary learning method...

Observational Learning

Albert Bandura did the early groundwork on observational learning. According to him, observational learning is a form of social learning that happens when we watch others. The best real-world example of this is his Bobo Doll Experiment.

In 1961, he placed children in a room with some adults and a giant Bobo doll clown. The children were split into two groups: one group saw the adults act mean towards the doll, and the other didn't pay much attention to the doll.

After the children watched the adults "play" for 10 minutes, they were moved into another room with more exciting toys. The intent was to take the toys away and frustrate the children. Albert Bandura moved them into a third room with a Bobo doll.

The goal was to observe the children's reactions to the Bobo doll when frustrated. The group that saw the adults acting in a violent manner, like hitting, kicking, and yelling at the doll... acted the same way!

This proves we can learn and re-enact behaviors by watching others act.

The Influence of Violent Video Games: A Modern Parallel

Building on Bandura's foundational work on observational learning, researchers in the digital age have turned their attention to modern media, especially video games. The question that arises is: Do violent video games influence aggressive behavior in a similar manner as the Bobo doll experiment?

Craig Anderson and Karen Dill, in 2000, spearheaded a study delving into this very topic. They found that individuals who played violent video games displayed heightened aggressive behaviors and thoughts, echoing the patterns observed in Bandura's experiment. The immersive nature of video games, where players often take on roles and actively engage in aggressive scenarios, brings a new dimension to observational learning.

Another area of modern-day observational learning is the impact of social media influencers on platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube. Youth behavior, body image, self-esteem, and even purchasing decisions can be significantly influenced by what they observe on these platforms.

While the mediums have evolved, Bandura's theory remains ever-relevant. The behaviors we witness, whether in real life, a video game, or a social media post, can profoundly influence our own actions and decisions.

Latent Learning

While latent learning isn't often classified as a primary method due to limited extensive research, its foundational premise challenges traditional learning paradigms. Unlike classical conditioning or operant learning, latent learning proposes that we can acquire knowledge without any immediate, visible reinforcement, punishment, or direct association with a particular behavior.

Edward Tolman's work stood in stark contrast to the dominant behaviorist views of his time. Many behaviorists strictly believed learning occurred only through direct reinforcements or punishments. But Tolman hypothesized differently and set out to test his theory through the now-famous Tolman and Honzik Maze experiment with rats.

Briefly, he designed a maze for rats. For 10 days, while some rats were rewarded with food upon completing the maze, others received no such reinforcement. Then, Tolman introduced a change: he began feeding the previously unrewarded rats upon their maze completion. The remarkable finding was that these rats, once rewarded, navigated the maze even more efficiently than the rats who had been consistently rewarded. This indicated that they had been learning the layout of the maze all along, even in the absence of direct rewards.

Tolman's groundbreaking experiment provided empirical evidence suggesting that organisms could learn without apparent rewards or punishments. Knowledge, it appeared, could remain "latent" and only become evident under specific circumstances. This shifted the narrative in psychological research, laying the foundations for further exploration of cognitive processes in learning.

Perceptual Learning

The ability to discern between two closely spaced musical tones or to read in braille proficiently epitomizes perceptual learning. Unlike other forms of learning that involve acquiring new facts or skills, perceptual learning focuses on refining our ability to detect, differentiate, and respond to sensory information.

At its core, perceptual learning involves sharpening our sensory experiences. Whether it's discerning the strategic relations between chess pieces on a board, reading more quickly and efficiently, or detecting minute abnormalities in an X-ray, this form of learning helps us better navigate and understand the complexities of our environment.

One of the unique facets of perceptual learning is its implicit nature. As learners refine their perceptual abilities, they often ignore the cognitive adjustments. This implicit progression is why experts in specific fields, like those who can precisely sort newborn chicks by sex, might struggle to articulate the exact cues they rely on. However, their high accuracy rate underscores the depth and efficiency of their learning.

So, why is perceptual learning so crucial? It fundamentally differentiates itself from other learning types by directly impacting our sensory systems. While traditional learning might equip us with factual knowledge or procedural abilities, perceptual learning fine-tunes our sensory apparatus, enhancing our direct interactions with the world. This enhancement allows for heightened awareness and paves the way for expertise in various disciplines where minute sensory differences can distinguish between novice and master.

Experiential Learning

My favorite way to learn is through experiential learning, or learning through experience or "doing." Some call this a "hands-on approach," while others say it's a form of operant conditioning.

Imagine you're trying to learn how to drive a car with a manual transmission. You can read all the books you want and watch thousands of videos on YouTube, but you'll never truly learn anything until you sit in the car and drive it. You have to feel the pressure of the clutch, the grinding of the gears, and the force the car feels as you accelerate to learn when and how to shift.

Some say this is a form of operant conditioning because you're getting micro-feedback through how well you drive. Didn't shift very well? Maybe let the clutch out a bit slower next time. Did you kill the car? Maybe you forgot to shift back to first gear at a stop sign.

How to Learn Better

Here are some simple ways to help you learn better and faster and store more information in your memory:

1) The Spacing Effect

The Spacing effect is a phenomenon that occurs when learning happens more efficiently when breaks are taken. One theory is that this works because our short-term memories are limited, and a break allows our brain to decide what to store and ignore.

Another theory says that the spacing effect works because you can review the information many times, increasing the repetition of you covering it and the chance of you recalling it.

2) Serial Position Effect

The Serial Position Effect also comes in handy to support you in taking breaks. According to the Serial Position Effect, you are likelier to remember the things of a list at the beginning (the primacy effect) and the end (the recency effect). When you break up your study session into multiple sessions, you will have more beginnings and endings to remember.

3) Von Restorff Effect

Also called the isolation effect, the Von Restorff effect makes us notice things that stand out. If you want to learn quicker to attend a party and ace your test, try making the most challenging curriculum stand out. For example, you could draw sketchbook doodles that relate to your study. Do you want to remember Piaget's cognitive developmental ages in order? Draw 4 kids, each with exaggerated features:

Sensorimotor kid: This kid is a baby with giant hands.

Preoperational kid: A toddler with a globe swirling around him. He thinks the world revolves around him

Concrete Operational kid: This kid is a teenager with acne who is stubborn yet can argue well. With every argument they participate in, a new pimple pops up.

Formal operational kid: This kid has a suit and tie and contemplates physics.

In each of these images, you are making something stand out; by doing so, you can remember these ridiculous images more.

4) Sleep

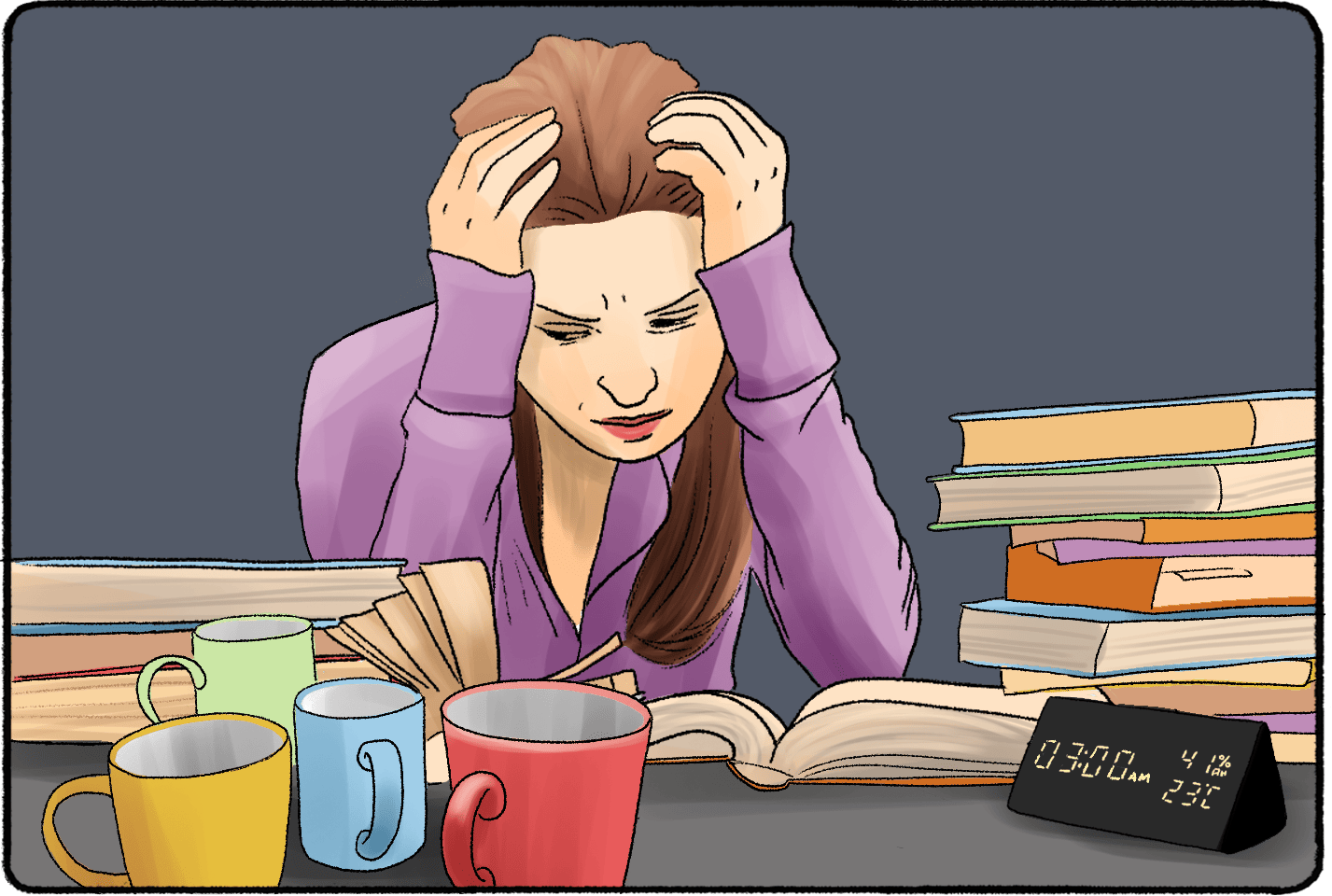

We all know that sleep is very important in storing information in your long-term memory. It also plays a vital role in the process of learning. But what exactly does it mean to get good sleep?

- Falling asleep within 30 minutes you did last night

- Waking up within 30 minutes you did yesterday morning

- Quiet

- Cold

- Dark

- No alcohol or caffeine within 6 hours

- Having an empty stomach

5) Use the information (teach)

One of the best ways to learn something for good is to apply the Feynman Technique. This technique has 4 steps:

1) Choose a concept

2) Teach your concept to a middle-schooler

3) Identify gaps in your own knowledge where you can't explain something

4) Review the gaps and simplify the teaching process

In short, this process makes you teach something to someone. The very process of doing so forces you to break it down into simple concepts that you yourself must first understand. By doing so, you are making it easier for you to remember. Time after time, the Feynman technique has been one of the best ways to understand something and remember it for a long time.