You probably understand how classical and operant conditioning use basic behaviorism theories, but what about a learning theory that falls outside behaviorism? Keep reading to learn more about observational learning.

In the early 20th century, behaviorism was the primary school of thought that explained how we behave. Behaviorists like Ivan Pavlov and John B. Watson used experiments to show that people may change their behaviors (or develop new behaviors) through conditioning. By understanding that our actions have consequences, we engage in some behaviors and stray from others.

By the mid-20th century, psychologists realized this explanation didn’t tell the whole story. People don’t have to experience behavior to perform that behavior later directly. They could simply observe the behavior to be able to perform it later.

What is Observational Learning?

Observational learning is a form of social learning that occurs through observing the behaviors of other people, things, and objects in the world.

Like many ideas associated with observational learning, this idea seems obvious now. In the 1960s, they were just making their way into academic psychology. I will break down observational learning, how it works, and the experiments that have brought this theory into the light.

Let’s get started. We can thank Albert Bandura for his early work on observational learning and the overarching social learning theory.

Albert Bandura

Albert Bandura is one of the most important psychologists in modern history. His work did not disprove the work of the behaviorists, but it added more pieces to the puzzle.

These puzzle pieces formed a bridge that connected traditional conditioning ideas to cognitive processes. Sure, people can learn a behavior after experiencing the consequences that come from that behavior. But even if people do not perform a behavior themselves, they can pick up on that behavior through observation.

The Bobo Doll Experiment

The Bobo Doll Experiment, led by Albert Bandura in 1961, serves as a cornerstone for understanding observational learning.

Methodology

Bandura's study involved children being exposed to two adult models: one behaving aggressively towards a Bobo doll and the other engaging in non-aggressive activities. The Bobo doll is a distinctive inflatable toy resembling a clown, designed to bounce back upright when knocked over.

In the experiment's first phase, children individually observed an adult in a room. Some witnessed the adult acting violently towards the Bobo doll — punching, kicking, and even using a hammer. In contrast, others saw the adult peacefully playing with other toys, ignoring the Bobo doll.

The children were placed in a different room with attractive toys in the subsequent phase. However, the toys were taken away from the children shortly after starting to play, a tactic designed to induce frustration. Finally, the children were placed in a room with a Bobo doll and other toys.

Results

The outcomes were quite revealing. Children who had observed the aggressive adult model were significantly more likely to display aggressive behavior towards the Bobo doll, mimicking the actions they had seen. They replicated the specific aggressive actions and improvised with weapons, even though the adult model hadn't done so. In contrast, children exposed to the non-aggressive adult showed less aggressive behavior towards the doll.

Implications

Bandura's Bobo Doll Experiment showed how individuals can learn merely by observing, without direct experiential learning. The findings challenged the prevailing belief that learning solely occurred through direct experience and reinforcement. It highlighted that observation alone could lead to new behaviors. This was groundbreaking in psychology, suggesting that behaviors could be learned socially by observing models, even without direct consequences or reinforcements.

Cultural examples

Nowadays, the idea of observational learning seems obvious. We all imitate others and model our behavior after the people in our lives. You participated in observational learning if you have ever dressed like your older sibling or used the same facial expressions as your parents.

Observational learning is one-way cultures are formed throughout geographical locations or age groups. Have you ever learned slang words or dance moves from your friends? Did you ever use a tutorial to learn how to put on makeup or walk in heels? Examples of observational learning are all around us!

How Observational Learning Works

The Bobo Doll experiment gives us a glimpse into children imitating adults. Imitation is a crucial piece of the social learning theory puzzle. But, as Bandura later theorized, we don’t simply imitate without cognitive thought. We think about our actions. We assess the possible consequences and whether or not we should perform a behavior.

Again, this sounds obvious, but behaviorists did not account for cognitive processes then. They believed that the conditioning we received had all power over our behaviors. Bandura’s theory says this is only one part of learning and performing behaviors.

Bandura believes that once observational learning occurs, humans go through mediational processes that help us decide whether or not we want to perform an action. The steps of that process are as follows:

Attention

We are in the presence of so many behaviors every day. Observing and learning everything that each person or animal does would be impossible. To learn a behavior, we must pay attention to it first. Attention is simply focusing our conscious thought on a task.

Memory/Retention

Not everything we see ends up in our memory storage. But retention and memory are crucial to observational learning - we can’t imitate something we don’t know how to do. You might have paid close attention to a television show where someone makes a tiramisu. But if you do not retain every step of the process, you cannot perform it.

This stage is easier to move through if the person observes the behavior multiple times. The more often someone watches a video on making tiramisu, the more likely the information will be stored in their memory.

Motor/Reproduction

We narrow the process even further when we reach the motor (or reproduction) stage. Just because you observe someone performing a behavior does not mean that you can imitate it.

Motivation

This is where cognitive processes really make an impact. Just because someone can perform an action does not mean that they will. People even have the ability to “turn off” involuntary actions that they might not be consciously doing.

The behaviorists believed that certain stimuli would result in an automatic response after conditioning. Psychologists like Bandura added another “hoop” for people to jump through before behaviors were performed.

Let’s go back to the tiramisu example. Just because a person knows how to make a tiramisu does not mean that certain stimuli will automatically cause them to enter the kitchen. They may use cognitive processes to plan out when they would like to make a tiramisu. They might ask themselves if they want to make the same old tiramisu or try a new dessert. Budget, time, and other responsibilities may come into play before they decide on making a tiramisu.

Michael Tomasello

Michael Tomasello's contributions to observational learning and cognitive theories significantly enhance our understanding of what differentiates humans from other animals.

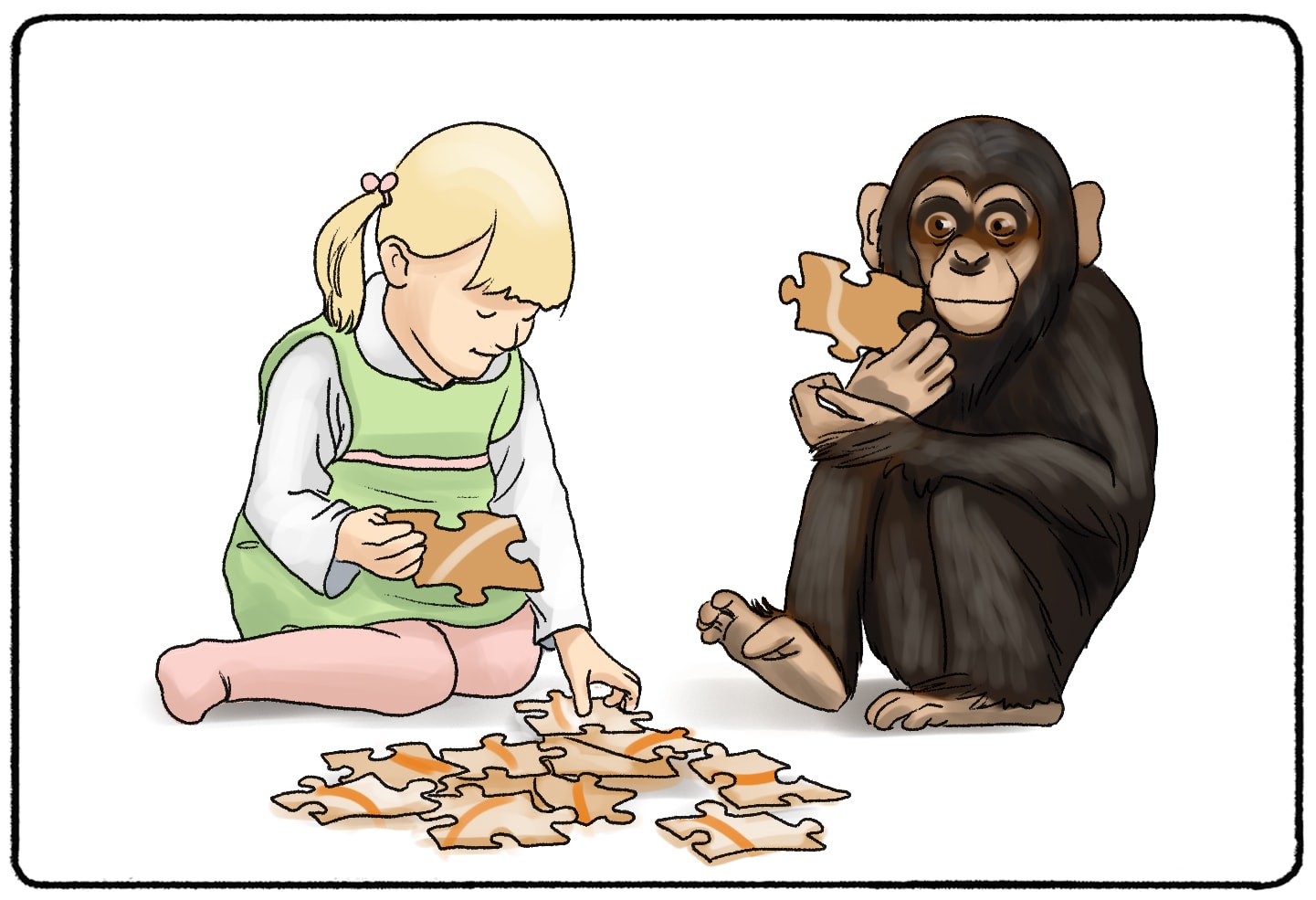

Since the 1980s, Tomasello, a renowned comparative psychologist, has delved deep into the nuances of observational learning. His experiments have often involved young primates, particularly chimpanzees and children, observing them as they witnessed adults solving rudimentary tasks.

One fascinating aspect of his study was witnessing how these subjects approached problem-solving after observation. While young primates predominantly relied on a trial-and-error approach, attempting to manipulate tools based on their own understanding, human children showed a distinct behavior. They directly imitated the actions they observed, essentially replicating the use of tools as demonstrated by adults. This behavior seems to underscore a human proclivity for imitation-based learning, suggesting a "why reinvent the wheel?" attitude.

Beyond observational learning, Tomasello's studies shed light on motivations and group dynamics. An intriguing observation was that, while chimpanzees mostly performed tasks aligned with personal gain, human toddlers were predisposed to collective benefits. This behavior in toddlers suggests an innate human tendency towards altruism and acting for the group's greater good, even from a young age.

Such findings resonate deeply with Tomasello's broader theories on the cooperative nature of human cognition. He posits that humans' unique cognitive abilities primarily derive from our evolutionary history of collaboration, which is distinct from other primates.

In essence, while Tomasello's research emerged from studying observational learning, it blossomed into a more profound exploration of human cognition's cooperative and imitative nature, setting us apart from our closest primate relatives.

Observational Learning in Other Animals

There are differences between how chimpanzees and humans learn through observation. However, observational learning does exist in primates and non-primates. These studies explain how humans observe, learn, imitate, and behave.

Take kittens, for example. In 1969, Phyllis Chesler conducted a study involving kittens. The kittens were split into three groups. One group watched their mother perform a task. The other group watched a different cat perform a task. The control group did not watch any cat perform the task.

After observation, the kittens who watched a cat were likelier to perform that task. Kittens who watched their mother were the most likely to perform the task.

This, again, might seem like common sense. We are more likely to imitate our parents than a stranger that we meet on the street. Later research has shown that we are likelier to imitate people we deem “successful” than those we don’t think are successful. The results of this study offer some explanations but also pose more questions about whose behavior we choose to imitate and why.

Just One Piece of the Puzzle

Observational learning has profoundly reshaped our understanding of human psychology, challenging behaviorist tenets and interlinking with numerous other psychological frameworks. This form of learning is intricately tied to cognitive processes, highlighting the critical roles of attention and memory in determining how we assimilate new behaviors and knowledge.

Furthermore, its principles intersect with social psychology and theories of personality development. Through observational learning, we understand how societal norms, peer influences, and interactions with key figures collectively shape our behaviors, attitudes, and identities.