Jean Piaget created one of the most well-known theories to explain a child's development. This page will review the basics of his theory on cognitive development.

If you have ever babysat, worked with children, or cared for younger siblings, you might have experienced moments where you noticed that the child just didn’t understand simple concepts. When you play peek-a-boo with a baby, it seems they genuinely don't know where you went. When you try to reason with a toddler, it appears they can’t understand why their brother also needs to eat food, even though they want it for themselves.

Other than causing hilarious moments of misunderstanding, these situations show how far along the child is in their cognitive development. Children develop certain concepts and skills as they age into young adults.

Who is Jean Piaget?

Jean Piaget was a Swiss psychologist who traveled to France to study children and intelligence. While studying children and raising three children of his own, he noticed that children would get the same questions wrong or misunderstand similar concepts at the same age.

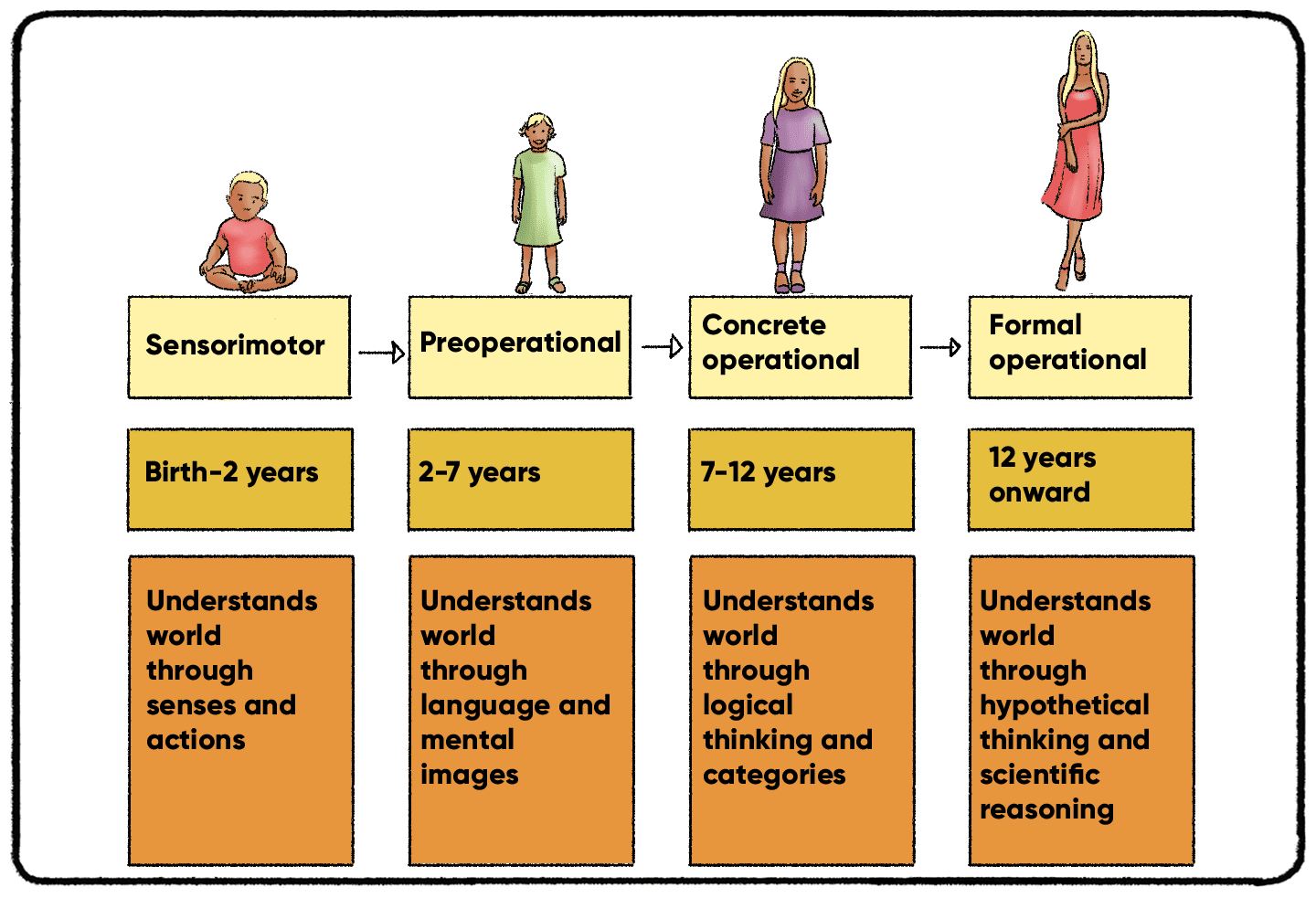

He developed a theory outlining the different stages children underwent to complete their cognitive development.

Piaget identified four stages that children must undergo to achieve full cognitive development. These four stages are the following:

If you want to remember the order of these four stages, use this mnemonic device: “Some People Can’t Focus.”

Let’s go through each of these stages.

Sensorimotor Stage

This is the first stage in the theory of cognitive development. It starts at birth and continues until the age of 2. During this stage, babies use their senses to develop schemas, a concept I will explain later, and learn about the world around them. Piaget breaks the sensorimotor stage into six substages.

The first substage is the refinement of basic reflexes that help the baby survive and feed. By the sixth substage, the baby has begun experimenting with different movements to get a reaction or experience sensations. They might hold a rattle, shake it, or throw it across the room to see the consequences of those actions.

In this stage, the child develops object permanence. When children are first born, they cannot understand that items exist outside of what they can see and hear. As they develop, they understand that even though their mother has walked out of the room, the mother still exists.

Preoperational Stage

The Preoperational Stage, the second stage of cognitive development, spans from ages 2 to 7. This is also known as “early childhood development.” While the child has already established that things exist outside of what they can see and hear, they are still limited to understanding things from their own perspective.

This is called egocentrism. However, as the child moves through the Preoperational Stage, the child begins to use symbolic play and thought to move out of an egocentric way of thinking. They can begin to see things from other points of view. While Piaget theorized that this development happened around age 7, other psychologists have concluded that egocentrism ends around age 3-5.

Children also start to develop language at this time. They use symbols to connect letters and words with sounds. This is why children begin to read as early as 2.

Throughout the Preoperational Stage, children also learn to combine different schemas to solve problems and understand the world around them. In the beginning stages of the Preoperational Stage, children have difficulty understanding Conservation. They can’t comprehend, for example, that the same amount of liquid can be held in two containers with different shapes. They may say a tall, skinny glass can hold more liquid than a short, wide glass of the same volume.

Concrete Operational Stage

The children reach the age of 6 or 7 and move into the Concrete Operational stage. They can begin to use logic to solve problems and come up with conclusions. Children are generally limited to inductive reasoning during this stage. For example, if they observe 10 dogs and all 10 dogs pant in the summertime, they can conclude that all dogs pant during the summertime.

Deductive reasoning comes later.

Children can begin to grasp the idea of Conservation in the Concrete Operational Stage. They also begin to understand Classification and Reversibility. Reversibility works well with Conservation. Children between the ages of 7-12 begin to understand that if you smash a ball of clay, it still has the same quantity as it did previously. With reversibility, the child begins to understand that smashing the ball of clay is reversible. They can simply roll the ball back up, maintaining the same quantity.

Classification is the ability to classify and organize objects. Through seriation, the children can also classify and order those objects due to logic.

These skills greatly contribute to a child’s ability to understand the world around them and solve problems. However, they are still limited and have one more stage in their cognitive development.

Stage 4: Formal Operational

The last and final stage in Piaget's theory of cognitive development doesn’t end when a child reaches their teenage years or even adulthood. When the child reaches the age of 11 or 12, they enter the Formal Operational Stage. This stage lasts for the rest of their lives.

The Formal Operational Stage is when the child uses abstract thinking and deductive reasoning to solve problems. They can think outside the world's rules and use more than just trial and error to approach problems.

Children also develop meta-cognition during this time. Not only can they start to use hypothetical situations to solve problems and solve more complex problems, but they can also think about their thought processes.

Influence of Environment, Culture, and Upbringing on Cognitive Development

Every child, while undergoing the stages of cognitive development, does so in the context of their environment, culture, and upbringing. These factors significantly influence the pace, sequence, and nuances of their developmental milestones.

- Environment: A stimulating environment can accelerate a child's cognitive development. For example, children exposed to a variety of sensory experiences, interactive toys, and engagement with caregivers tend to develop cognitive skills faster than those in deprived settings.

- Culture: Cultural norms can define what skills are emphasized or de-emphasized during a child's upbringing. In some cultures, memorization might be emphasized more than critical thinking, influencing the way cognitive skills evolve. Moreover, cultural practices and beliefs can shape the schemas children develop. For instance, children in collectivist cultures might develop schemas centered on community and relationships faster than those in individualistic cultures.

- Upbringing: Parenting styles and familial structures play a pivotal role. Children in authoritative households, where they're encouraged to ask questions and explore the world around them, might progress differently in certain cognitive areas than those in more restrictive environments.

- Language and Communication: The complexity and structure of the language spoken at home can influence cognitive development, especially in terms of abstract thinking and expression. Bilingual children, for instance, often showcase flexibility in thinking due to their ability to switch between languages.

- Educational Systems: The educational structure a child is exposed to can significantly alter their cognitive progression. Systems that promote critical thinking, creativity, and exploration might lead to different developmental trajectories compared to those that emphasize rote learning.

It's essential to recognize that while Piaget's theory provides a structured overview of cognitive development, the individual journey of each child is nuanced and influenced by a myriad of external factors. Recognizing these influences not only provides a more holistic understanding of a child's cognitive development but also underscores the importance of providing an enriching, culturally aware, and supportive environment for every child.

Schemas

In the context of Piaget's Theory of Cognitive Development, as children journey through the various stages, they continuously amass knowledge and craft mental structures called schemas. Schemas are essentially cognitive blueprints or frameworks that help us organize and interpret the world. As children encounter new experiences and information, these schemas are developed, adjusted, and expanded. Let's delve into some primary schema types:

- Person Schemas: These revolve around information about specific individuals. For instance, a child may develop a schema that their grandmother always wears glasses and smells like roses. As they encounter more people and note various distinguishing characteristics, their person schemas evolve.

- Self-schemas: These are deeply rooted in one's own self-perception and understanding. They encompass information about oneself and evolve with every new personal experience. For a young child, a self-schema might be rudimentary like recognizing they have blonde hair. However, as they mature, self-schemas become more intricate, encapsulating personality traits, personal values, and self-worth.

- Event Schemas (or Scripts): These schemas relate to routine activities or events. A child might develop an event schema around bedtime: brush teeth, read a story, and then lights out. These become deeply ingrained, and deviations from the 'script' might be met with confusion or resistance, especially in younger children.

- Social Schemas: These involve general knowledge about how the world operates, especially in a social context. It can encompass societal norms, roles, and behaviors expected in particular settings. An example might be the expectation to say "please" and "thank you." As children grow and are exposed to diverse cultures and societal norms, their social schemas can adjust to incorporate a broader worldview.

Evolution Across Stages

- Sensorimotor Stage: Schemas during this stage are mostly based on sensory and motor experiences. A baby might develop a schema that shaking a rattle will produce sound.

- Preoperational Stage: As children start to engage in pretend play, their schemas become more sophisticated, encompassing symbols and language. Their self-schemas start to form more distinctly, as they recognize themselves in mirrors and photos.

- Concrete Operational Stage: Children begin to understand the concept of reversibility and conservation, leading to more advanced event schemas. Their social schemas also expand as they engage in group activities and learn about societal norms.

- Formal Operational Stage: Schemas during this stage become abstract. Adolescents can think hypothetically and deduce conclusions from premises. Their self-schemas might become intertwined with philosophical thinking about identity and existence.

As children transition through these stages, it's vital to recognize that while the foundational essence of schemas remains, their complexity, depth, and breadth evolve tremendously. It underscores the dynamic nature of cognitive development and the intricate tapestry of experiences that shape our understanding of the world.

Assimilation and Accommodation

As I said earlier, we acquire new schemas, but we also change those schemas as we acquire new information and thought processes. These two processes are called assimilation and accommodation.

Assimilation

Assimilation is adjusting the schema you currently have to make room for new or even conflicting information. You also learn where and how to store the information that you currently have.

Technology is a great example of how we assimilate new information. You might have had your first exposure to a word processor when you played on a typewriter. You learned how to place your fingers on the keys and saw that pressing each letter created a letter on the page.

However, as technology evolved and you grew up, you were introduced to new schema, like Microsoft Word. You still put your fingers on the same keys and saw letters pop up on the screen, but you also learned how to Save, Print, Copy, and Paste the letters you typed.

Throughout the development of technology and your need to use a word processor, you become better and better and organizing the skills and information needed to complete your tasks. Your original schema about word processing was never proved to be “wrong” but was merely expanded by new information.

Accommodation

Accommodation is the process of altering or modifying existing schemas to fit new information. Sometimes, this might even involve the formation of an entirely new schema.

For instance, consider children's understanding of animals. When they first encounter a gorilla, they might classify it broadly as a hairy primate under the schema "gorilla". However, as they gain more exposure and knowledge, they realize not all hairy primates are gorillas. Subsequently, they refine their schema, differentiating between "gorillas", "baboons", "chimpanzees", and "orangutans". Each of these animals then has its own distinct schema, changing the child's original, more generalized understanding of what a gorilla represents.

Similarly, schemas can be influenced by societal and familial inputs, which aren't always accurate. For example, children raised in prejudiced environments might grow up with skewed schemas about certain groups of people, influenced by their parents' biases. If they're taught to believe that a particular group of people is inferior, they'll view the world through that lens.

However, as they grow and interact with the broader world – perhaps meeting individuals from that group, being exposed to diverse viewpoints, or receiving education that challenges their biases – they may come to realize that their initial schema was flawed. This realization would prompt the child to accommodate the new, more accurate information, thereby reshaping or even replacing the old prejudiced schema with a more informed and equitable understanding. This highlights the dynamic nature of cognitive development and the ongoing interplay of experience, learning, and personal growth.

Equilibration (balance of Assimilation and Accommodation)

Assimilation and accommodation are two key learning processes. You cannot expand your worldview without making room for new information and developing new schema. But which one is most important?

Piaget believed that an equal amount of both assimilation and accommodation were necessary to foster cognitive development. Children benefited most when they could make room for new information that didn’t change their existing schemas and could alter schemas with new, more factual information.

How Piaget's Theory of Cognitive Development Affects Teaching and Interacting With Children

As you learn more about the different stages of cognitive development, you can use activities to foster a child’s development. You can encourage pretend play to develop a child’s understanding of symbols. You can give them logic puzzles to help them refine their skills during the Concrete Operational Stage.

Continue learning about each stage of cognitive development. As you do, you will learn more about when children acquire different skills. Use this information to help your students or the children in your life through the four stages.