Have you ever heard someone tell a new mom that 3 or 4 was a “fun age?” If you have kids, cousins, or siblings at that age, you know it’s true. Kids are becoming more independent and fun between the ages of 3-5. Erik Erikson called this time in a person’s life the “Play Age.”

If you have been enjoying my content on The Eight Stages of Psychosocial Development, you already know who Erikson is. If you haven’t, I recommend that you start with the link I just shared.

This article is about the third stage of Psychosocial Development, which occurs between the ages of 3 and 5.

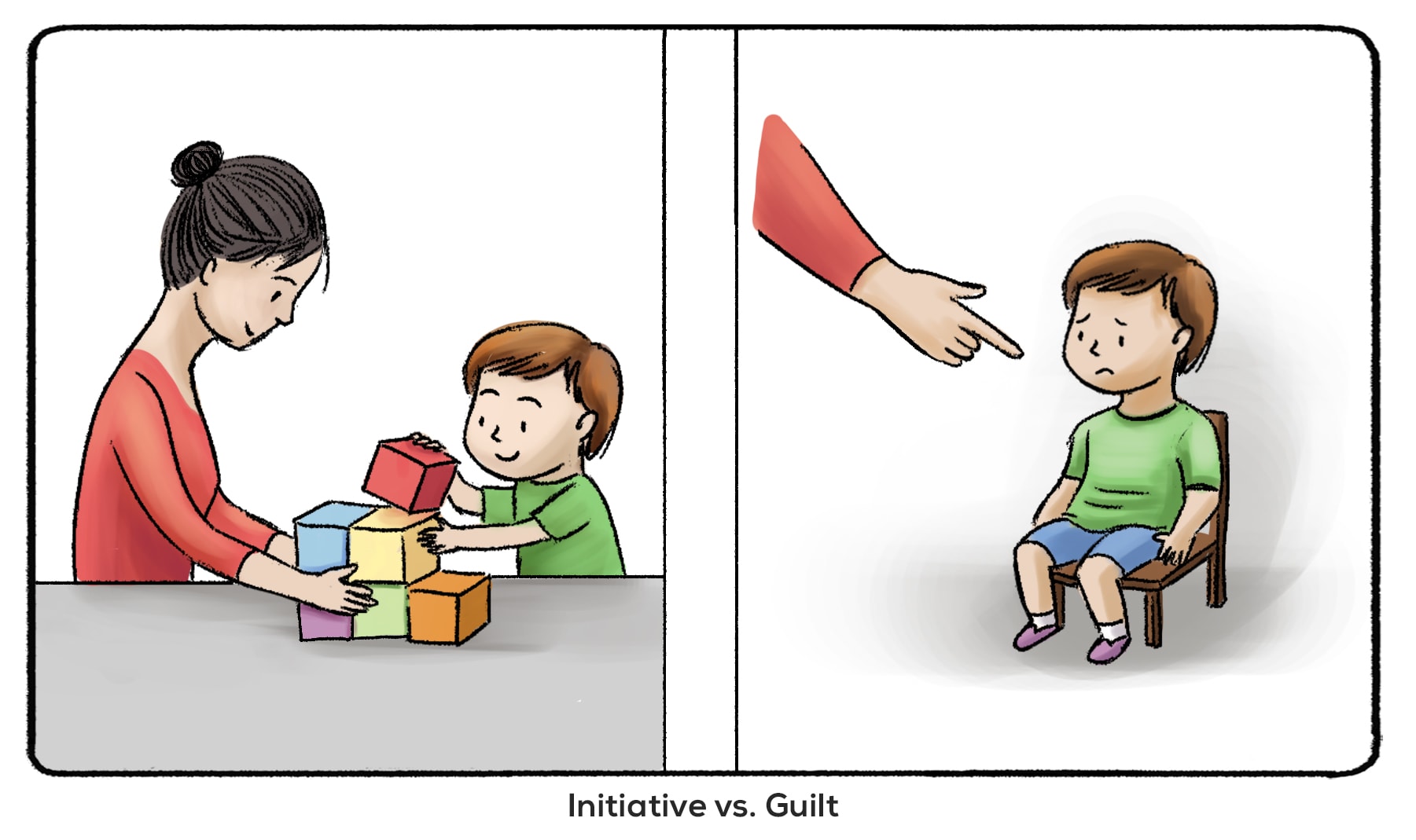

The third stage of psychosocial development is Initiative vs Guilt. It occurs between the ages of 3 and 5 after the child wrestles with the Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt crisis. Ideally, the child has developed a sense of autonomy and the ability to make decisions for themselves.

During this stage, the child also feels that the world is trustworthy (that comes from the first stage of development.) Unfortunately, some children move forward with shame and doubt regarding their bodies and decisions.

This stage takes decision-making to the next level. Children in the third stage of social development undergo a new crisis: Initiative vs. Guilt. If they successfully complete this stage, they develop the virtue of purpose. Interactions with parents, family members, and even other children may develop the outcome of this psychological crisis.

Initiative vs Guilt Examples: What Happens?

During this third stage, children are learning how to play with others. In their play groups, they understand that everyone has a role. This allows some people to take initiative and take charge.

How Do Children Learn How to Take Initiative?

By taking the initiative, a child might develop a new game. They might map out the “rules” of make-believe. The child might be the one to suggest that it is time to play or time to do something else. Members of the playgroup may follow along or push back. Different playgroup members may also fight for the “top spot.”

These conflicts and interactions are good for the child’s development - it helps them develop a sense of initiative. This is the first time in a child’s life that they can explore being a leader or how a leader operates. Children can also experience planning, executing these plans, and compromising with others. If you have ever been around a three- to five-year-old, you know that many questions are asked during these ages. But these questions only help the child understand how to take charge, make plans, and make things happen when they want them to happen.

How is a Sense of Guilt Developed?

Like the second stage, initiative is developed if the child is encouraged to make plans or take charge. Exploration of role-playing only helps to further this development along. If a child is discouraged or kept away from group play, they may develop a sense of guilt. If a child’s questions are dismissed or left unanswered, they might begin to feel guilty for bringing up those questions in the first place. They may regret speaking their mind or asking for the things they want.

Like mistrust or shame and doubt, guilt can have long-lasting consequences. If a child learns that taking initiative is something to feel guilty about, they will fail to branch out, make plans for themselves, or take on leadership roles. They may instead choose to rely on parents or other authority figures when making decisions about their lives. This has consequences in later stages of psychosocial development (identity vs. role confusion), where the person must decide who they are and how they want to live.

The early childhood phase is not just marked by the vivid imagination children possess but also by their exploration of leadership and assertiveness. Imaginary friends are but one facet of this expansive period of development. They serve as a testament to a child's burgeoning creativity and their endeavor to understand the world and their place within it. These make-believe companions can play various roles, from comforting during loneliness to being a scapegoat when the child breaks a rule.

However, navigating leadership and assertiveness often comes with its own challenges, and it's not limited to the realm of make-believe. Take, for instance, a young girl named Mia. At the age of three, Mia is often seen directing play scenarios with her peers, instructing them on which toy to pick or what role to play in a pretend game. While this can be perceived as being "bossy," it's Mia's way of understanding leadership dynamics.

Another example can be drawn from a boy named Liam, who, after watching his parents make decisions at home, decides he wants a say in what the family has for dinner or which park to visit over the weekend. While seemingly serious or assertive, these demands are his attempts to grasp the concept of decision-making and its implications.

And then there's Aisha, who insists on wearing mismatched socks or a superhero cape to school every day. While this might come off as defiant to adults, it's Aisha's way of expressing her individuality and making choices that reflect her identity.

All these scenarios underline the same developmental theme: children in this stage are experimenting with autonomy, testing boundaries, and trying to understand the complex interplay of leadership, decision-making, and self-expression. While these attempts might seem brash or frustrating to adults, they're essential milestones in a child's journey of understanding initiative and their role in the world around them.

One or The Other May Not Be the Answer

Other children or family members may also make a child feel guilty during this stage. After all, children in play groups may also be in this stage of development and learning how to be leaders. Conflict over leadership and who gets to make decisions isn’t always easy to navigate but is crucial for development.

Guilt isn’t always a bad thing during this stage. A child may feel guilt when they realize they (metaphorically) stepped on another child’s toes or made other children feel bad. At this stage, the child might start to see that their role in a group may require them to sacrifice their needs and wants for the sake of others. Guilt is not always bad, but children must be encouraged to play with others and make mistakes to develop a healthy balance of initiative and guilt.

What Makes Initiative vs Guilt Different Than Autonomy vs Shame?

This question was asked on the psychologystudents subreddit, and the answers may help you understand the distinction between these two stages.

Kindlywolf1169 had this to say:

If a child doesn’t build a strong autonomy, they won’t feel confident in their actions.

Initiative versus Guilt is about impulse control and becoming cooperative. It is when children start seeing “how far they can push boundaries”. So the example I was given at school was that it’s time for a child to go to sleep but the child is watching TV. You told the child that you will give them 10 more minutes and they need to go to bed. You come back 10 minutes later and what do you see? The child is still watching TV. So they’re going to see how far they can go by adding extra time. Then, there are consequences imposed when they go too far. If the child is disciplined too harshly, that is what creates the guilt part. The child is learning to maintain a sense of initiative without imposing on the freedom of others.

Talnethin said:

The biggest difference would probably be personal vs. interpersonal. One has negative effects from a lack of confidence in self and the other has negative effects from the feeling of not being of use (which is to some extent developed by people around them). Children at that age tend to get that great feeling from doing something to help somebody (no matter how small). Developing that tendency and observing positive social development with people requesting the help would probably be an interesting paper to write.

Mongosmoothie explained it this way:

I think of it as exploring autonomy (oh wow I can get this blanket myself) vs getting initiative (I’m going to get this blanket myself). If the kid is getting everything done for them, they will doubt themselves of what they’re capable of doing for themselves. If this continues, they eventually feel guilt about wanting/doing things themselves.

Ages 3-5 In Other Stages of Development

Erikson’s theory focuses on social development. Psychologists like Jean Piaget and Sigmund Freud focused their theories on other aspects of childhood development. You may find similarities and stark differences when you compare what is happening from ages 3-5 in Erikson’s theory versus other theories.

Jean Piaget’s Stages of Cognitive Development: A child is in the preoperational stage from the ages of 3-5. They already have object permanence but only think in concrete terms. Piaget also suggested that children at this age are largely egocentric. They have not yet developed empathy and only see the world through their perspective. Yes, children may start to take initiative and play games, but tension will arise as the children try to share, make decisions, or resolve problems among the group.

Sigmund Freud’s Stages of Psychosexual Development: Children between the ages of 3-5 are in the phallic stage of psychosexual development. Yes, you read that right. In each stage, the child has a different erogenous zone that influences their behavior. Freud suggested that during this time, the child discovers the differences between men and women. They also discover their affection for the opposite-sex parent. This is known as the Oedipal complex (Freud’s colleague Carl Jung added that girls go through an Electra complex.) Although Freud’s stages of psychosexual development are no longer widely accepted by modern psychologists, they are still fascinating to study.

Lawrence Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development: Children are in the first stage of moral development until 9. They are not yet making their own decisions regarding moral vs. immoral. If their parents give them a rule, they follow it “because they said so.” Kohlberg and Piaget have similar views on egocentrism during this time of life. A child does not see beyond themselves until later in their development. (This is addressed in later stages of Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development, too.)

Industry vs. Inferiority

Initiative vs. guilt is the third stage of psychosocial development. The fourth stage is industry vs. inferiority. Before a child enters school, they may have moved through this stage of development with a sense that they can take charge or that others can take charge. But they likely haven’t grasped that they can compare themselves to others. This is the central idea in industry vs. inferiority.

Fostering Healthy Initiative in Early Childhood

Creating an environment that promotes positive growth is essential as your child ventures into the world of initiative, autonomy, and self-expression. Here are some tips to guide them through this stage while minimizing feelings of guilt:

- Encourage Exploration: Provide ample opportunities for your child to explore various activities, from arts and crafts to outdoor play. These experiences help them understand their preferences and strengths.

- Set Boundaries with Empathy: While it's important to set limits, it’s equally vital to do so with understanding. Instead of a firm "No," try explaining why a certain behavior is discouraged, helping them understand the reasons behind the rules.

- Celebrate Efforts, Not Just Outcomes: Applaud their efforts, even if the result isn't perfect. This fosters a growth mindset, where the journey becomes more valuable than the destination.

- Encourage Decision-Making: Allow them to make small choices, such as what clothes to wear or which storybook to read before bed. It helps them understand the value of decision-making and its consequences.

- Open Communication Channels: Regularly converse with your child about their feelings, experiences, and concerns. It makes them feel valued and assures them they can always come to you with their problems.

- Role Model Positive Behavior: Children learn by observing. By demonstrating constructive ways to take initiative and handle challenges, you provide them with practical templates for their behavior.

- Avoid Overpraising: While encouragement is essential, avoid empty praises. Instead, be specific about what you're praising them for. For example, instead of saying, "Good job," you can say, "I loved how you shared your toys with your friend today."

- Mitigate Guilt with Constructive Feedback: If they make a mistake, rather than inducing guilt, provide feedback on how they can improve or handle the situation differently next time. Ensure they know that everyone makes mistakes and that learning from them is important.

- Maintain Consistency: Children find comfort in routine and consistency. While spontaneity is great, ensuring a consistent framework helps them feel more secure.

- Seek Feedback from Teachers and Caregivers: Regularly engage with other adults in your child’s life. Their insights can offer a broader understanding of your child’s behavior and areas they might struggle with outside the home.

Your child will undoubtedly experience both triumphs and setbacks in early childhood development. Creating a nurturing environment that celebrates their initiative and guides them through challenges with empathy lays a foundation for a confident, self-assured individual who approaches life with enthusiasm and resilience.