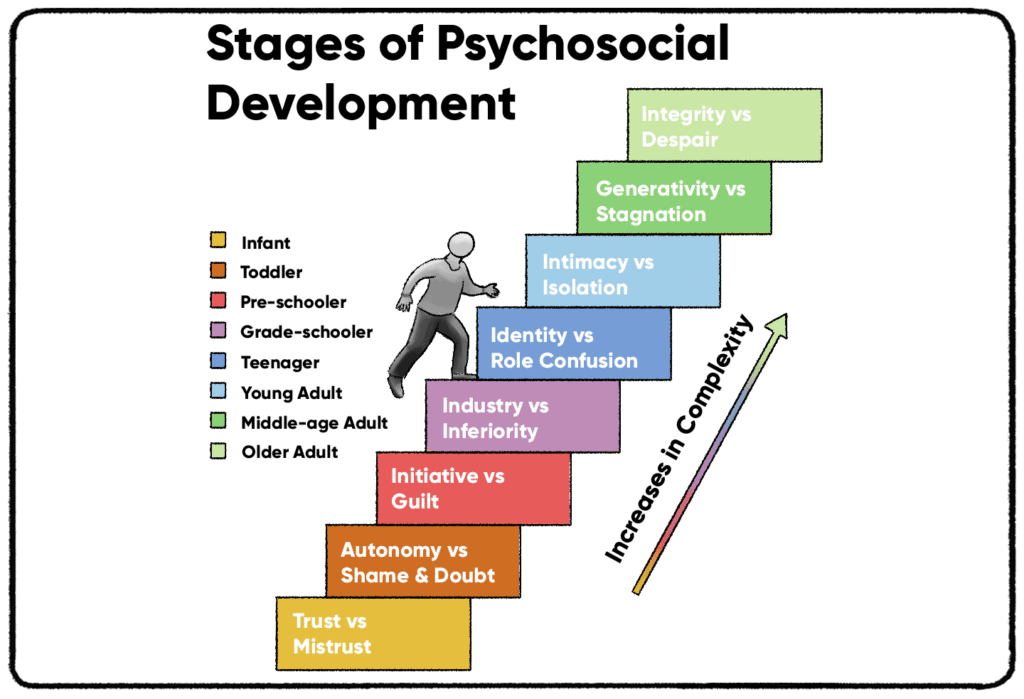

Erik and Joan Erikson developed eight stages of psychosocial development that outline each person's crises. The second psychosocial stage is autonomy vs. shame, also known as autonomy vs. shame and doubt.

What Is Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt?

Autonomy vs. Shame is the second psychological crisis a child experiences in their psychosocial development. The first is Trust vs. Mistrust, which occurs starting at birth. This second stage occurs between 18 months and three years of age.

As infants become toddlers, they explore many things outside their social development. They are learning to walk, crawl, eat independently, and communicate their needs. With these new abilities come new choices. Do they walk away from their mother to explore the house or go to their mother for guidance? Should they communicate when they need to use the bathroom? Can they refuse food if they are not hungry or ask for it when they are? They develop autonomy, shame, and doubt as they answer these questions for themselves and face various repercussions or rewards.

Preparing For Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt

Before this stage begins, the toddler is an infant and, for the most part, helpless. The "trust vs. mistrust" stage forces them to explore trust or mistrust with their parental figures. The parent must meet the child's needs during this time: food, water, shelter, warmth, comfort, etc. If the child is in need, they will cry for attention. It is then up to the parent to fulfill those needs and show the child they can be trusted.

According to Erikson, if a child's needs are met by their parent or guardian in a timely manner, they will develop a general sense of trust in the world. They will trust, at least, that their needs are met. Neglected children will develop mistrust. This trust vs. mistrust conflict can affect a person into their adulthood. Many psychologists compare Erikson's trust vs. mistrust stage and attachment styles.

Going into Stage 2, a child should feel comfortable enough to take risks and try new things, knowing their needs will ultimately be met.

How Do Children Develop Autonomy?

When a child is encouraged to make these decisions on their own, they gain a sense of autonomy. Autonomy is a state of self-governance. If a child feels comfortable making decisions for themselves about their needs, they have a sense of autonomy.

Autonomy gives someone independence. If a child is comfortable with self-governance, they can explore making decisions without relying on a parent. This will carry them into later stages in life, where they have to make more and more decisions for themselves.

How Can Parents Encourage Autonomy?

While the mother was pivotal during the initial stage of Psychosocial Development, in Stage 2, both parents play an instrumental role. They can cultivate a child's budding sense of autonomy or inadvertently sow seeds of shame and doubt if they're not mindful.

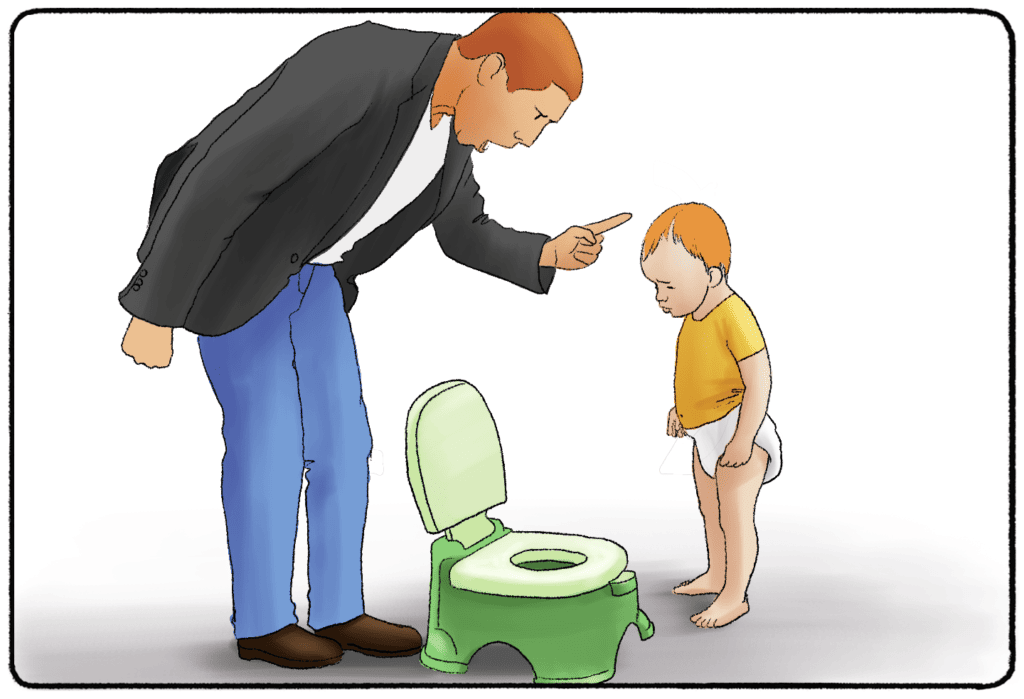

Toilet Training: The Balancing Act

A significant milestone in this stage is toilet training. Children also begin communicating these needs to their caregivers as they recognize their bodily cues. Parents' reactions during this time can lay the foundation for either autonomy or shame.

- Supportive Strategies: Celebrate small victories. Each time a child uses the toilet or communicates the need, applaud the effort. Employing tools like reward charts can be effective in reinforcing positive behavior.

- Avoiding Negativity: Accidents will happen. Instead of expressing frustration or resorting to punishment, be patient. Focus on reassurance. Conveying disappointment can lead the child to internalize shame or fear around natural bodily functions.

The drive towards autonomy extends beyond the bathroom. Children will express preferences in clothing, food, activities, and play as they grow.

- Encourage Exploration: Allow children to make simple choices, such as picking an outfit or a snack. This empowers them and validates their decision-making abilities.

- Setting Boundaries with Empathy: While it's essential to encourage autonomy, boundaries are equally crucial. If a child opts for an impractical winter outfit on a hot day, rather than outright refusal, try empathizing and offering choices: "I love that sweater too! But it's warm today. How about we wear this lighter shirt now and save the sweater for a cooler day?"

- Constructive Feedback: Children will sometimes make choices that aren't ideal. Instead of admonishing them, engage in dialogue. For instance, if they overindulge in sweets and later feel unwell, talk about the connection and guide them towards healthier choices next time.

Handling Shame and Doubt Proactively

If a child seems hesitant or displays signs of doubt:

- Open Communication Channels: Encourage them to express their feelings. It might be as simple as a toy they're struggling to play with or something deeper. Listen actively.

- Reframe Failures as Learning Opportunities: If a child attempts something and fails, celebrate the effort. "I'm so proud of you for trying! Every time we try, we learn. Let's figure this out together."

- Model Behavior: Children learn by observing. Displaying your autonomy and showing resilience in the face of setbacks can be a powerful example.

In conclusion, the Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt stage is foundational in a child's journey toward becoming independent and confident. Parents and caregivers play a pivotal role in shaping this journey. They can ensure their child navigates this stage with a burgeoning sense of autonomy by approaching each situation with understanding, patience, and proactive strategies.

Will

When successfully navigated, each stage in Erikson’s psychosocial theory imbues an individual with a virtue—a strength that emerges from successfully resolving the stage's central conflict. In the case of the second stage, "Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt," the virtue acquired is "Will".

"Will," in this context, refers to the belief in one's ability to act with intention, make choices, and exert control over one's actions. This virtue lays the groundwork for many facets of an individual's later development:

- Decision-Making: Adults who have cultivated a strong sense of "Will" in childhood tend to be more decisive. They believe in their ability to make choices and stand by them. Conversely, without this foundational belief, individuals may constantly second-guess themselves or avoid decision-making altogether, leading to feelings of drift and aimlessness in life.

- Self-Efficacy: This term, often used in psychology, refers to one's belief in their ability to achieve goals. Those who have developed "Will" have an inherent sense of their capabilities and are more likely to take on challenges and persist in adversity.

- Resilience: Life is fraught with challenges and setbacks. Individuals with a well-developed sense of "Will" can better navigate these challenges, believing in their ability to influence outcomes and recover from hardships.

- Relationships: An individual’s sense of autonomy and control can significantly influence interpersonal relationships. Those with a strong sense of "Will" tend to assert their needs and boundaries more effectively, fostering healthier, more balanced relationships.

- Career Success: In professional environments, the ability to make decisions, take initiative, and believe in one's actions can be crucial to success. Individuals with a well-developed sense of "Will" often excel in leadership roles and are proactive in their careers.

On the flip side, if this virtue isn't fully cultivated during the Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt stage, several challenges can manifest later in life:

- Learned Helplessness: As alluded to in the example with Seligman’s dogs, individuals might develop a mindset that perceives events as out of their control, even when they aren't. This can lead to passive behaviors, lack of motivation, and depression.

- Dependency: Without a strong sense of "Will," individuals might constantly seek external validation or rely heavily on others for decision-making, leading to over-dependency in relationships and lack of personal agency.

- Low Self-Esteem: Continual doubt in one's abilities can erode self-worth, making individuals more susceptible to criticism and less confident in social situations.

- Avoidance of Responsibility: A lack of belief in one's control can lead to a tendency to avoid responsibilities, be it in personal or professional spheres.

The virtue of "Will" is not just a product of childhood development but a foundational element that profoundly influences an individual's journey through life. Its presence or absence can shape how one interacts with the world, navigates challenges, and perceives oneself.

Example of Autonomy vs. Shame in Psychology

In 1967, Martin Seligman conducted a monumental experiment on helplessness and will. He separated the dogs into one of three groups and gave the dogs a series of electric shocks. One group was able to “turn off” the shocks by completing an action, and the other group could not turn off the shocks.

Later, Seligman put the dogs in another situation in which they received electric shocks. All they had to do was take a few steps to turn the shocks off. He observed that the dogs in the second group I mentioned felt helpless and unwilling to try anything. They assumed they were not in control and that nothing they could do would help the situation.

I mention this now because the second stage of psychosocial development puts children into very similar situations to those dogs. (Of course, no electric shocks are involved.) In the second stage of psychosocial development, children explore whether they are in control. They enter a psychological crisis, leaving it with a sense of autonomy, shame, and doubt.

During this time in a child's life, they will learn how to:

- Listen to stories

- Listen to rules (but do not understand they need to follow them)

- Use their imaginations

- Tell you generally what happened earlier that day

- Show signs of independence

- Talk in three-word sentences

They are still unable to:

- Fully express their emotions

- Empathize with others

- Share time, toys, or other things they want

- Sit still and focus for a long period of time

Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt Compared to Other Stages of Development

Remember that autonomy vs shame and doubt occur between 18 months and 3 years old. Child psychologists have always taken an interest in this age. Most development theories have one or two stages that focus on this time period, but not all of them highlight the development of autonomy or shame. Let's compare Erikson's observations of children of this age to Freud, Piaget, and other child psychologists.

Sigmund Freud's Stages of Psychosexual Development

Freud also believed that toilet training was a huge part of a child's development from ages 18 to 36 months, but not for the reasons you might think. He developed the Stages of Psychosexual Development. At each age, a child's id is focused on satisfying a different erogenous zone. From 1-3, the id is focused on the anus and bowel movements. This is why Stage 2 of Freud's Stages of Psychosexual Development is called the "Anal Stage."

Like Erikson, Freud believed that learning to relieve oneself gives a child a sense of autonomy and independence. He also encouraged parents to appropriately reward their children for using the toilet. Unlike Erikson, Freud predicted specific outcomes if the child faced too much lenience or harsh punishments during this stage of life. Parents and guardians who were too relaxed during this stage may raise an "anal-expulsive" child. The child is disorganized, may have random outbursts of extreme emotion, or is generally a bit careless in their actions.

On the other hand, parents and guardians who are too strict during toilet training may end up with an "anal-retentive" child. (This phrase is more commonly known, probably because it's less graphic than "anal-expulsive!") An anal-retentive child is anxious, very Type A, and rigid. A child who is on either extreme may develop psychological issues down the line.

Freud's theories are not accepted by most of today's psychologists, but they have significantly influenced modern psychology, which is why we continue to study them today.

Jean Piaget's Stages of Cognitive Development

Between 18-36 months, a child transitions from Jean Piaget's Sensorimotor Stage to the Preoperational Stage. Rather than focusing on how the child views their needs, Piaget focused on how the child interacts with the world. The Preoperational Stage is when children begin to understand the world through symbols and play. They might, for example, play with a doll that they label as "mommy" or "me." In exploring these relationships, they can explore autonomy vs. shame. Although a child is egocentric through the early parts of this stage, they can explore their relationship with others and how they can fulfill their needs rather than relying on someone else.

Lawrence Kohlberg's Stages of Moral Development

According to Kohlberg, children are in the first stage of moral development until 9. They are not yet making their own decisions regarding moral vs. immoral. If their parents give them a rule, they follow it “because they said so.” Like Piaget, Kohlberg sees a child at this age as largely egocentric. A child does not see beyond themselves until later in their development. This perspective is addressed in the later stages of Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development, too.

Preparing for the Next Stage of Development

Whether or not the child has developed a sense of autonomy, they move on to their next psychological crisis around age 3. Erikson's third stage of psychosocial development is "Initiative vs. Guilt." In this phase, the child will continue to explore their autonomy and how they can begin to fulfill their own needs. In later stages, the child transitions to discovering who they are and how they fit into this world.

All of Erikson's early stages are building blocks for the later stages. If a child does not trust the world or experience a lot of shame and doubt, they will have a harder time exploring themselves and their place in the world. These early years are crucial to a child's development.