When faced with stress, how do you determine the best way to alleviate it? Do you go for a run? Eat something? Listen to loud music? Your choices are often influenced by recalling which solutions have consistently provided relief.

For many people, deciding how to deal with emotions or what they should do next requires looking back to past experiences. If a quick walk around the block made you feel better after a stressful day, you may decide to take a quick walk around the block the next time you have a stressful day. This decision-making process, concluding previous experiences, is known as inductive reasoning.

What is Inductive Reasoning?

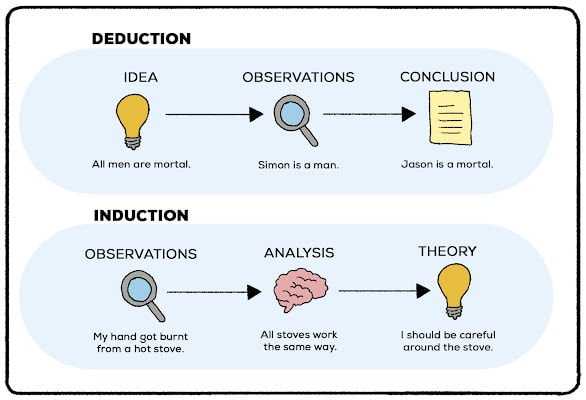

Inductive reasoning is a method where specific observations or experiences are used to reach a broader, general conclusion. In contrast to deductive reasoning, which starts with a general statement and examines the possibilities to reach a specific conclusion, inductive reasoning begins with specific examples and tries to form a general rule.

Consider the example I presented earlier:

Premise A: Your mother told you that walking around the block would be good for stress relief.

Premise B: Your doctor recommends 30 minutes of walking daily to relieve stress.

Premise C: Last week, after a stressful day, you walked around the block and felt better.

From these observations, you might conclude that 30 minutes of walking around the block will help alleviate stress.

In essence, inductive reasoning uses individual observations and experiences to formulate more general conclusions.

For inductive reasoning to work, you must collect past experiences and observations. We do this naturally, just by living! Then, when you encounter a situation similar to these past experiences, you draw on them for a better picture of outcomes.

For example, maybe you have dealt with little siblings or cousins who respond to certain reinforcements or punishments in certain ways. When you get a job as a teacher, you may draw on those experiences when you make decisions about discipline because you have concluded that all children respond well to one strategy or another.

Who is the Father of Inductive Reasoning?

Francis Bacon is considered the father of inductive reasoning, as he is considered the father of empiricism. Empiricism is the theory that all of our knowledge is pulled from our experiences and senses (as opposed to more innate knowledge.) Inductive reasoning uses our senses and experiences to make judgments.

Characteristics of Inductive Reasoning

If you understand deductive reasoning, you might notice that the induction process isn’t as solid.

Rather than using broad generalizations, induction takes single experiences or facts as premises. This premise could be something you’ve personally experienced or witnessed or an experience told to you by a friend, parent, TV personality, etc.

The premises provide some evidence to build a conclusion. You might think, “But the conclusion might not be true if you’re just pulling from a one-time occurrence or a handful of experiences.” To that, I say you are right.

Conclusions derived from induction don’t make them the truth. They show the probability of an event occurring. Sure, you are likely to feel better after you’ve walked around the block, but there is no solid guarantee that you will feel less stressed after your next walk.

There are problems within induction (I’ll speak to those later,) but often, our inductive reasoning helps us make the best choices for ourselves. If we find ourselves taking a walk and still feeling stressed, we may use inductive reasoning to break down what other events could affect our stress, our walk, and the connection between the two.

Of course, the statement that “inductive reasoning generally gives us a usable conclusion” is a conclusion derived from inductive reasoning itself.

Exploring the Philosophies Behind Inductive Reasoning

The concept of inductive reasoning has been deeply entwined with philosophical discourse since its inception. Philosophers have contemplated and debated the nature, validity, and limitations of induction. Delving into the philosophical underpinnings of inductive reasoning can offer a richer understanding of the topic.

- David Hume and the Problem of Induction: The Scottish philosopher David Hume is perhaps the most famous critic of inductive reasoning. In the 18th century, he posed the "Problem of Induction," which questions the logical justification for making predictions based on past experiences. He argued that we cannot rationally justify the belief that the future will resemble the past, making all inductive conclusions inherently uncertain.

- Karl Popper and Falsifiability: 20th-century philosopher Karl Popper proposed a significant shift in scientific methodology, emphasizing falsifiability over verification. Rather than using induction to confirm hypotheses, he believed science should aim to falsify them. For Popper, no number of positive outcomes can confirm a scientific theory, but a single counterexample can disprove it.

- Bayesianism: Rooted in the work of the 18th-century statistician and minister Thomas Bayes, Bayesianism is a philosophical approach to probability and induction. Bayesianism focuses on how subjective beliefs should evolve in the light of new evidence. It uses a mathematical framework to incorporate prior beliefs with new evidence to arrive at posterior beliefs.

- Pragmatism and Induction: American philosophers like C.S. Peirce argued for the practical value of inductive reasoning. From a pragmatist perspective, even if induction can't be justified in absolute logical terms, it is a necessary and effective tool for navigating our world. Its consistent success in a myriad of contexts, for pragmatists, grants it legitimacy.

- Evolutionary Justifications: Some contemporary thinkers suggest that our inductive capacities have evolutionary roots. If our ancestors hadn't been adept at making reliable predictions based on past experiences (e.g., predicting that certain predators are dangerous because of past encounters), they wouldn't have survived. Thus, while induction might never achieve logical certainty, its evolutionary origins could indicate its general reliability.

In essence, while inductive reasoning remains a practical tool for navigating our experiences and predicting outcomes, its philosophical underpinnings reveal a world of debate about its validity, scope, and limitations. Understanding these philosophical perspectives enhances our grasp of the nuanced nature of induction and how it shapes and is shaped by broader epistemological concerns.

Where Is Inductive Reasoning Used?

Pretty much everywhere! Any time we draw on prior experiences to conclude, we can use inductive reasoning. We don’t always do this, but we can!

Examples of Inductive Reasoning In Everyday Life

Inductive reasoning is extremely common in our everyday world. A lot of the decisions you make are based on inductive reasoning. You have a headache and take a painkiller because past experiences have shown you that those painkillers work well in treating headaches.

Maybe you take a certain set of side streets because, in past experiences, it has been faster than the highway.

Maybe you buy CBD oil for your dog because, in the past, he has always responded well to it and not gotten sick.

This is just one type of induction. There are also different types of inductive reasoning that we use every day.

Example 1: If I Leave For Work at ___, I Can Avoid Traffic

Inductive reasoning pulls from our experiences to make conclusions. Let’s say you get a new job and have to be there at 9 a.m. every day. Unfortunately, you tend to encounter a lot of rush-hour traffic on your route. You experiment with leaving for work at different times.

One day, you leave for work at 8:30 and arrive at 9:15. The next day, you leave for work at 8:00 and arrive to work at 8:35. Another day, you leave for work at 8:15 and arrive to work at 8:50.

You conclude that rush hour traffic picks up between 8:15 and 8:30. If you leave for work around 8:15, you’ll get to work on time.

Example 2: You Pet a Cat on Its Head, and It Starts Purring. Pet The Cat On Its Belly and It Hisses…

Inductive reasoning can be used to conclude about one specific person, place, or thing. Let’s say you get a new cat. Your friend tells you that their cat loves belly rubs and asks if your cat is the same way. To answer your friend, you have to draw from past experiences. One time, you pet the cat on its head, and the cat started purring. Petting the cat on its back evoked a similar reaction. But the cat got finicky if you tried to rub its belly. You conclude that your cat doesn’t love belly rubs.

Example 3: Throwing Up From Tequila

Experimentation can lead to a lot of inductive reasoning. Take the first time you got drunk. You probably drank too much and got sick. The next time you got drunk, you also got sick. Later, you drink again - guess what happened? You got sick.

Through your observations and experimentation, you conclude that too much alcohol makes you sick. Sure, someone may have told you that you would get sick after drinking. But if you come to that conclusion through a series of observations and events, you have used inductive reasoning.

Example 4: Geometry

You have used inductive reasoning in your everyday life for years without knowing it. Many people don’t learn about inductive reasoning until they take a psychology course. Others learn about inductive reasoning in geometry or higher-level math classes.

Mathematicians use a specific process to create theorems or proven statements. Inductive reasoning cannot produce fool-proof theorems, but it can start the process. If someone is observing something, for example, that two triangles look congruent, they are using inductive reasoning. They have more work to do before they can prove once and for all that the two triangles are congruent, but inductive reasoning helps them kick things off.

Drawing Conclusions About the Past

Inductive reasoning doesn’t just predict what will happen in the future. It can also tell us what probably happened in the past. Take this example.

Premise A says that most babies where you come from are born in modern hospitals.

Premise B says that your friend Denise was born sometime in the last 20-30 years.

Premise C says that Denise was probably born in a hospital.

Of course, that is likely to be true, but it doesn’t mean it is. If Denise tells you that she was born in the back of a pickup truck, you shouldn’t argue with her based on the conclusion you came to through induction.

So there are many different ways that you can use inductive reasoning to sort out what has happened in the past and what may happen in the future. But you may not always be right.

Analogies

You can also use analogy to conclude different properties of items. Analogies are comparisons between two things that help to clarify information. Through induction and analogy, you can predict likely characteristics, uses, etc., of different things.

Here’s an example.

Spinach is a green vegetable. It’s high in Vitamin A and Vitamin C but has a slightly bitter taste.

Spinach is a great vegetable to add to a healthy smoothie.

Kale is also a green vegetable. It’s also high in vitamins A and C, with a slightly bitter taste.

Using induction, one may assume that kale is also a great vegetable to add to a healthy smoothie.

We often use this type of induction to replace items that we cannot find at the home or the grocery store.

Statistics

If I told you that 90% of people like my videos, I probably use inductive reasoning. If you hear any statistic that covers a large population, it was probably derived from inductive reasoning.

Statistics usually come from surveys or studies. We can’t study everyone worldwide, so we divide our studies into small, controlled groups. Once we get data from that control group, we use it to predict how a current population feels, reacts to a drug, makes a decision, etc.

You may take a survey among college students and find out that 66% of the students in the study don’t like cheese. You may conclude that 66% of college students don’t like cheese. You may also use this data to predict whether the next college student you meet will or won’t like cheese.

Control groups may give us a good look at the larger population if professionals choose the participants. They are also only effective at reaching conclusions if the control group is sizable enough.

If you surveyed two women and one of them said that they were a feminist and the other one said they were not, you should not conclude that half of all women are feminists. You would need to expand your survey greatly, account for demographics, and look at your study before you could come to any conclusions worth sharing or publishing.

Puzzles

Test your inductive reasoning skills with this puzzle posted on Reddit!

Problems with Inductive Reasoning

You might have been able to spot some of the holes that we can poke in inductive reasoning.

Small control groups

Poor control groups are one way to come to flawed conclusions through inductive reasoning. The feminist example that I just used happens all the time.

Online surveys conducted by organizations who are not professionals may take a survey from a few hundred people, share the conclusion, and spark outrage from people who may not agree or be offended by the result. But the outrage is all based on lies and false conclusions.

Outside Factors

Arguably the biggest problem with inductive reasoning is that the conclusion is not a guaranteed truth. Sure, you might like spinach in your smoothies, and it is very similar to kale. But you might not like the taste of kale. Or the texture of kale. Or the smoothie you try and make with kale doesn’t blend well with the smoothie you made with spinach.

Does that completely dismantle the entire idea of inductive reasoning? Not at all. But it’s something to be aware of.

Outside factors will almost always impact your conclusions. There are a lot of premises that are not necessarily true that you could use to argue that kale is or is not good in a smoothie based on what you know about the similarities between spinach and kale.

And, just because the first smoothie you make with kale doesn’t taste as good as the smoothie you made with spinach doesn’t mean the next smoothie you make with kale will taste bad. But you might avoid kale for a while based on your past experiences using it in a smoothie. That’s still using inductive reasoning.

Inductive reasoning is easy to do, convenient for finding answers, and works most of the time. But it should not be the sole process used to make conclusions about a group of people, a very important outcome, and other things that may make a huge impact.

Inductive vs Deductive Reasoning

Inductive reasoning is often taught side by side with deductive reasoning. We learn inductive reasoning much earlier than we learn deductive reasoning. Jean Piaget, the famed psychologist in child development, theorized that children develop inductive reasoning around 7.

It makes sense. A child touches a hot stove, and they burn their hand. The next time they are near the hot stove, they are likely to remember what happened the last time they touched the stove. They’ll avoid the hot stove and avoid the burn.

Deductive reasoning comes to children at ages 11 or 12. It’s a form of “top-down” logic to inductive’s “bottom-up” logic.

You need to understand basic, broad facts about the world to conclude them. With deductive reasoning, you don’t have memories of experiences to guide your reasoning. You have to know things like “all dogs are mammals” or “all humans are mortal” to narrow your reasoning down to conclusions that you might not be able to grasp.

Another big difference between induction and deduction is that deductive reasoning has stricter rules. Every premise has to be true. If there are exceptions to the premise, you can’t come to a true conclusion. Your conclusion may be valid, but it won’t be true. (And yes, there is a difference in philosophy.)

Test Your Knowledge of Inductive Reasoning

Alright, it’s test time! I will give you three questions to test your knowledge of induction. No cheating!

First question:

Induction uses ______ as evidence to come to conclusions.

Answer: Past experiences!

Second question:

Can you get the truth from induction?

Answer: Not in the philosophical sense. Since each premise does not have to be true, induction will only tell you what is likely true.

Last question:

Which form of reasoning do children develop first?

A: Deduction

B: Induction

C: They develop them at the same time!

The answer is B. Children develop the ability to learn through inductive reasoning at age 6 or 7. They typically understand—deduction later in their development.