We receive rewards and punishments for many behaviors. More importantly, once we experience that reward or punishment, we are likely to perform (or not perform) that behavior again in anticipation of the result.

Psychologists in the late 1800s and early 1900s believed that rewards and punishments were crucial to shaping and encouraging voluntary behavior. But they needed a way to test it. And they needed a name for how rewards and punishments shaped voluntary behaviors. Along came Burrhus Frederic Skinner, the creator of Skinner's Box, and the rest is history.

What Is Skinner's Box?

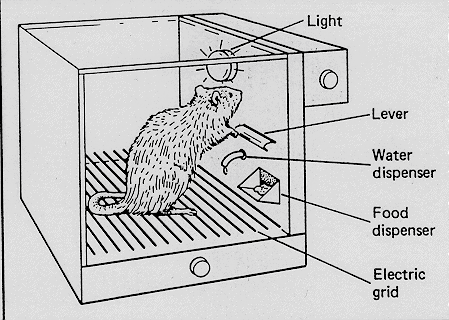

The "Skinner box" is a setup used in animal experiments. An animal is isolated in a box equipped with levers or other devices in this environment. The animal learns that pressing a lever or displaying specific behaviors can lead to rewards or punishments.

This setup was crucial for behavioral psychologist B.F. Skinner developed his theories on operant conditioning. It also aided in understanding the concept of reinforcement schedules.

Here, "schedules" refer to the timing and frequency of rewards or punishments, which play a key role in shaping behavior. Skinner's research showed how different schedules impact how animals learn and respond to stimuli.

Who is B.F. Skinner?

Burrhus Frederic Skinner, also known as B.F. Skinner is considered the “father of Operant Conditioning.” His experiments, conducted in what is known as “Skinner’s box,” are some of the most well-known experiments in psychology. They helped shape the ideas of operant conditioning in behaviorism.

Law of Effect (Thorndike vs. Skinner)

At the time, classical conditioning was the top theory in behaviorism. However, Skinner knew that research showed that voluntary behaviors could be part of the conditioning process. In the late 1800s, a psychologist named Edward Thorndike wrote about “The Law of Effect.” He said, “Responses that produce a satisfying effect in a particular situation become more likely to occur again in that situation, and responses that produce a discomforting effect become less likely to occur again in that situation.”

Thorndike tested out The Law of Effect with a box of his own. The box contained a maze and a lever. He placed a cat inside the box and a fish outside the box. He then recorded how the cats got out of the box and ate the fish.

Thorndike noticed that the cats would explore the maze and eventually found the lever. The level would let them out of the box, leading them to the fish faster. Once discovering this, the cats were more likely to use the lever when they wanted to get fish.

Skinner took this idea and ran with it. We call the box where animal experiments are performed "Skinner's box."

Why Do We Call This Box the "Skinner Box?"

Edward Thorndike used a box to train animals to perform behaviors for rewards. Later, psychologists like Martin Seligman used this apparatus to observe "learned helplessness." So why is this setup called a "Skinner Box?" Skinner not only used Skinner box experiments to show the existence of operant conditioning, but he also showed schedules in which operant conditioning was more or less effective, depending on your goals. And that is why he is called The Father of Operant Conditioning.

How Skinner's Box Worked

Inspired by Thorndike, Skinner created a box to test his theory of Operant Conditioning. (This box is also known as an “operant conditioning chamber.”)

The box was typically very simple. Skinner would place the rats in a Skinner box with neutral stimulants (that produced neither reinforcement nor punishment) and a lever that would dispense food. As the rats started to explore the box, they would stumble upon the level, activate it, and get food. Skinner observed that they were likely to engage in this behavior again, anticipating food. In some boxes, punishments would also be administered. Martin Seligman's learned helplessness experiments are a great example of using punishments to observe or shape an animal's behavior. Skinner usually worked with animals like rats or pigeons. And he took his research beyond what Thorndike did. He looked at how reinforcements and schedules of reinforcement would influence behavior.

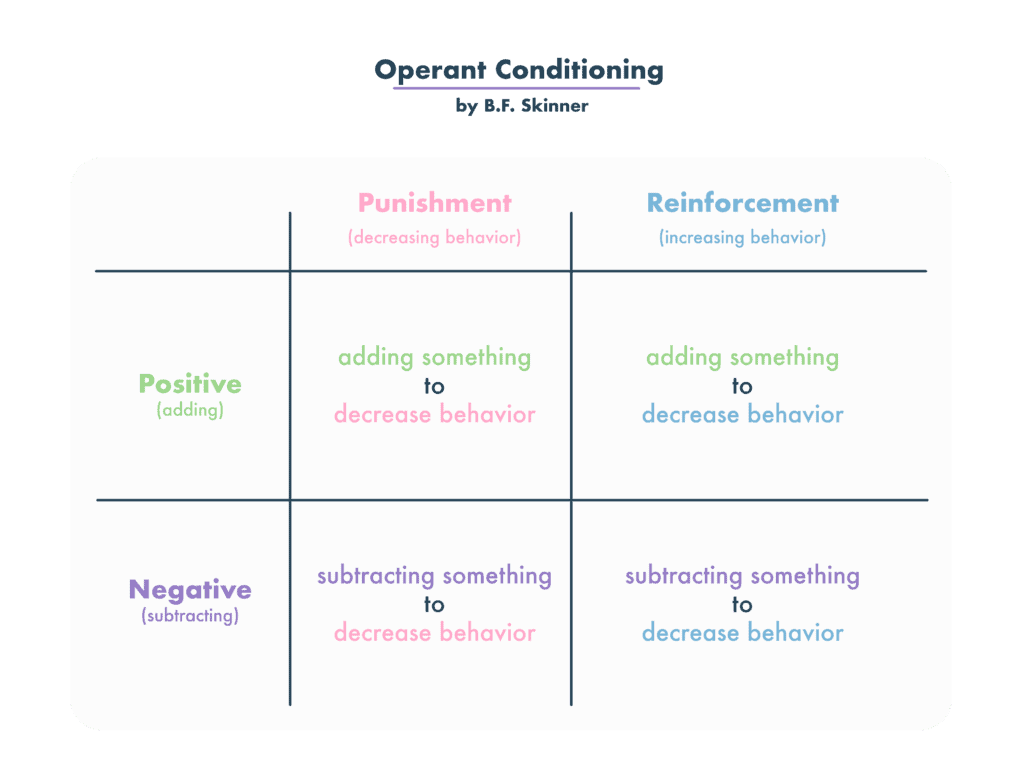

About Reinforcements

Reinforcements are the rewards that satisfy your needs. The fish that cats received outside of Thorndike’s box was positive reinforcement. In Skinner box experiments, pigeons or rats also received food. But positive reinforcements can be anything added after a behavior is performed: money, praise, candy, you name it. Operant conditioning certainly becomes more complicated when it comes to human reinforcements.

Positive vs. Negative Reinforcements

Skinner also looked at negative reinforcements. Whereas positive reinforcements are given to subjects, negative reinforcements are rewards in the form of things taken away from subjects. In some experiments in the Skinner box, he would send an electric current through the box that would shock the rats. If the rats pushed the lever, the shocks would stop. The removal of that terrible pain was a negative reinforcement. The rats still sought the reinforcement but were not gaining anything when the shocks ended. Skinner saw that the rats quickly learned to turn off the shocks by pushing the lever.

About Punishments

Skinner's Box also experimented with positive or negative punishments, in which harmful or unsatisfying things were taken away or given due to "bad behavior." For now, let's focus on the schedules of reinforcement.

Schedules of Reinforcement

We know that not every behavior has the same reinforcement every single time. Think about tipping as a rideshare driver or a barista at a coffee shop. You may have a string of customers who tip you generously after conversing with them. At this point, you’re likely to converse with your next customer. But what happens if they don’t tip you after you have a conversation with them? What happens if you stay silent for one ride and get a big tip?

Psychologists like Skinner wanted to know how quickly someone makes a behavior a habit after receiving reinforcement. Aka, how many trips will it take for you to converse with passengers every time? They also wanted to know how fast a subject would stop conversing with passengers if you stopped getting tips. If the rat pulls the lever and doesn't get food, will they stop pulling the lever altogether?

Skinner attempted to answer these questions by looking at different schedules of reinforcement. He would offer positive reinforcements on different schedules, like offering it every time the behavior was performed (continuous reinforcement) or at random (variable ratio reinforcement.) Based on his experiments, he would measure the following:

- Response rate (how quickly the behavior was performed)

- Extinction rate (how quickly the behavior would stop)

He found that there are multiple schedules of reinforcement, and they all yield different results. These schedules explain why your dog may not be responding to the treats you sometimes give him or why gambling can be so addictive. Not all of these schedules are possible, and that's okay, too.

Continuous Reinforcement

If you reinforce a behavior repeatedly, the response rate is medium, and the extinction rate is fast. The behavior will be performed only when reinforcement is needed. As soon as you stop reinforcing a behavior on this schedule, the behavior will not be performed.

Fixed-Ratio Reinforcement

Let’s say you reinforce the behavior every fourth or fifth time. The response rate is fast, and the extinction rate is medium. The behavior will be performed quickly to reach the reinforcement.

Fixed-Interval Reinforcement

In the above cases, the reinforcement was given immediately after the behavior was performed. But what if the reinforcement was given at a fixed interval, provided that the behavior was performed at some point? Skinner found that the response rate is medium, and the extinction rate is medium.

Variable-Ratio Reinforcement

Here's how gambling becomes so unpredictable and addictive. In gambling, you experience occasional wins, but you often face losses. This uncertainty keeps you hooked, not knowing when the next big win, or dopamine hit, will come. The behavior gets reinforced randomly. When gambling, your response is quick, but it takes a long time to stop wanting to gamble. This randomness is a key reason why gambling is highly addictive.

Variable-Interval Reinforcement

Last, the reinforcement is given out at random intervals, provided that the behavior is performed. Health inspectors or secret shoppers are commonly used examples of variable-interval reinforcement. The reinforcement could be administered five minutes after the behavior is performed or seven hours after the behavior is performed. Skinner found that the response rate for this schedule is fast, and the extinction rate is slow.

Skinner's Box and Pigeon Pilots in World War II

Yes, you read that right. Skinner's work with pigeons and other animals in Skinner's box had real-life effects. After some time training pigeons in his boxes, B.F. Skinner got an idea. Pigeons were easy to train. They can see very well as they fly through the sky. They're also quite calm creatures and don't panic in intense situations. Their skills could be applied to the war that was raging on around him.

B.F. Skinner decided to create a missile that pigeons would operate. That's right. The U.S. military was having trouble accurately targeting missiles, and B.F. Skinner believed pigeons could help. He believed he could train the pigeons to recognize a target and peck when they saw it. As the pigeons pecked, Skinner's specially designed cockpit would navigate appropriately. Pigeons could be pilots in World War II missions, fighting Nazi Germany.

When Skinner proposed this idea to the military, he was met with skepticism. Yet, he received $25,000 to start his work on "Project Pigeon." The device worked! Operant conditioning trained pigeons to navigate missiles appropriately and hit their targets. Unfortunately, there was one problem. The mission killed the pigeons once the missiles were dropped. It would require a lot of pigeons! The military eventually passed on the project, but cockpit prototypes are on display at the American History Museum. Pretty cool, huh?

Examples of Operant Conditioning in Everyday Life

Not every example of operant conditioning has to end in dropping missiles. Nor does it have to happen in a box in a laboratory! You might find that you have used operant conditioning on yourself, a pet, or a child whose behavior changes with rewards and punishments. These operant conditioning examples will look into what this process can do for behavior and personality.

Hot Stove: If you put your hand on a hot stove, you will get burned. More importantly, you are very unlikely to put your hand on that hot stove again. Even though no one has made that stove hot as a punishment, the process still works.

Tips: If you converse with a passenger while driving for Uber, you might get an extra tip at the end of your ride. That's certainly a great reward! You will likely keep conversing with passengers as you drive for Uber. The same type of behavior applies to any service worker who gets tips!

Training a Dog: If your dog sits when you say “sit,” you might treat him. More importantly, they are likely to sit when you say, “sit.” (This is a form of variable-ratio reinforcement. Likely, you only treat your dog 50-90% of the time they sit. If you gave a dog a treat every time they sat, they probably wouldn't have room for breakfast or dinner!)

Operant Conditioning Is Everywhere!

We see operant conditioning training us everywhere, intentionally or unintentionally! Game makers and app developers design their products based on the "rewards" our brains feel when seeing notifications or checking into the app. Schoolteachers use rewards to control their unruly classes. Dog training doesn't always look different from training your child to do chores. We know why this happens, thanks to experiments like the ones performed in Skinner's box.