Do you know who Urie Bronfenbrenner is? Learn about this Russian American psychologist and his significant contributions to the fields of developmental psychology and ecological psychology.

Who Was Urie Bronfenbrenner?

Urie Bronfenbrenner is best known for devising the bioecological model of development. His research highlighted the multitude of social and environmental factors that may impact child development. He was also instrumental in establishing the Head Start governmental program that assists low-income children and families in the United States.

Urie Bronfenbrenner Family Background

Urie Bronfenbrenner was born on April 29, 1917, in Moscow, Russia. His parents, Alexander and Eugenie, were both Jewish. To escape the Russian Revolution, his father moved to the United States in 1922 and a year later, was joined by his wife and six year old Urie. Bronfenbrenner’s father was a neuropathologist and obtained a medical position at a hospital in Pennsylvania. Bronfenbrenner attended the local primary school which had a large population of immigrant children.

Bronfenbrenner described his mother as a “lover of literature, art, and music.” She continued to speak Russian while in the United States and was especially fond of Russian literature. She would often read Russian novels and poetry to her son. As a result of her strong influence, Bronfenbrenner ended up learning Russian before English, though he eventually became a fluent English speaker.

Early Life

The family later moved to Upstate New York where Alexander was appointed as lead researcher at Letchworth Village—a residential facility for people with physical and cognitive disabilities. Bronfenbrenner grew up on the grounds of the institution and attended Haverstraw High School.

Bronfenbrenner considered the residents of the institution as his “friends and companions.” Three of the residents worked in the family home as helpers and served as Bronfenbrenner’s caregivers. As an adult, Bronfenbrenner recalled how the IQs of these residents seemed to improve when they worked with his family, despite the fact that they were “supposed to be mentally retarded.” This observation helped to pique his interest in development. As he got older, Bronfenbrenner also assisted his father in conducting experiments on the condition then known as “feeble-mindedness.”

Educational Background and Career

In 1934, Bronfenbrenner received a scholarship to Cornell University, where he studied psychology. He graduated in 1938. He went on to complete a masters degree in developmental psychology at Harvard University and later earned his PhD from the University of Michigan. His dissertation on the development of children within their peer group marked the beginning of a lifelong interest in researching child development.

During the latter years of World War II (from 1942 to 1946) Bronfenbrenner served in the United States army as a field psychologist at several military hospitals. In 1948, he obtained a position at his alma mater, Cornell, as Professor of Psychology and Human Development.

In addition to being an avid researcher, Bronfenbrenner was a prolific writer who authored numerous papers that detailed the findings of his studies on children and their families. He was also an activist who engaged directly with policymakers and sought to convince them of the importance of early childhood education and family support on the basis of his research findings. His aim was not merely to comprehend the complexity of human development but to translate this understanding into policy and practice.

Bronfenbrenner conducted cross-cultural work in a variety of countries including the Soviet Union, China, Israel, and Western Europe. During his time in the Soviet Union, he served as an exchange scientist at the Institute of Psychology in Moscow.

The Head Start Program

When World War II ended, the relationship between the United States and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) became strained. Those tensions increased in the late 1940s during the Cold War. As Bronfenbrenner was able to speak Russian fluently, he made himself available for scholar exchange opportunities so that he could conduct research on child rearing and family practices in the USSR. In 1970, he published the book Two Worlds of Childhood: US and USSR in which he noted a number of differences between both countries.

Bronfenbrenner viewed children in the USSR as “well-mannered, attentive, and industrious.” He also claimed that these children displayed a “strong motivation to learn” and had “a readiness to serve society.” Bronfenbrenner believed that children in the USSR benefited from “a more homogenous set of standards.” In the USSR, children were raised “collectively” as there was a general harmony between the values of the family and the values of society.

In the United States, the situation was very different. Bronfenbrenner claimed that American families were being given a continuously shrinking role as a “socialising agent.” He pointed to the fact that an increasing number of parents were spending less time with their children because they had to work day and night to pay the bills. He believed that after World War II, much of the responsibility of raising children had shifted from the family to other settings such as schools.

It is important to note that schools may not view it as their role to raise children. While adult teachers are present, children spend much of their time talking with and learning from their peers. Bonfenbrenner claimed that American children had less contact with responsible adults, and as a result, they had a harder time transitioning to society. To address the issue, Bronfenbrenner encouraged the United States government to invest in social programs and offer support to low-income families.

In 1965, he helped to establish the Head Start programme, a federal early childhood education programme for children from low-income families. He also served as a consultant to the federal government and was often called as an expert witness on matters of child development and testified before numerous committees and the US Congress.

After Lyndon B. Johnson became President of the United States in 1963, he began laying the groundwork for the Head Start program. He founded the Office of Economic Opportunity and appointed Bronfrenbrenner as a member of the design committee. Head Start was established in 1965 and helps to counteract the educational issues poor children face by giving them an educational input before they start school. The program is still operational and now includes a variety of interventions to help disadvantaged children and their families.

Ecological Systems Theory

Although Bronfenbrenner was fascinated by the field of child development, he was critical of previous theories of child development and dissatisfied with the experimental methods used by researchers in the 1940s. He believed that there were few benefits to studying children in a lab. Bronfenbrenner argued that putting children in a “strange environment” would elicit “strange behavior” from them and that the data collected from these experiments were ecologically invalid. He also noted that many experiments on child development were unidirectional; that is, they focused exclusively on how children are affected by other people or factors in the environment.

Bronfenbrenner believed that the environment in which a child is raised has a profound impact on his or her development. In order to study how a child develops, it is important to pay attention to the child’s immediate environment as well as the broader environment. Bronfenbrenner also claimed that studies should be bi-directional because children may influence the people and environment around them. He addressed these concerns when he developed his ecological systems theory.

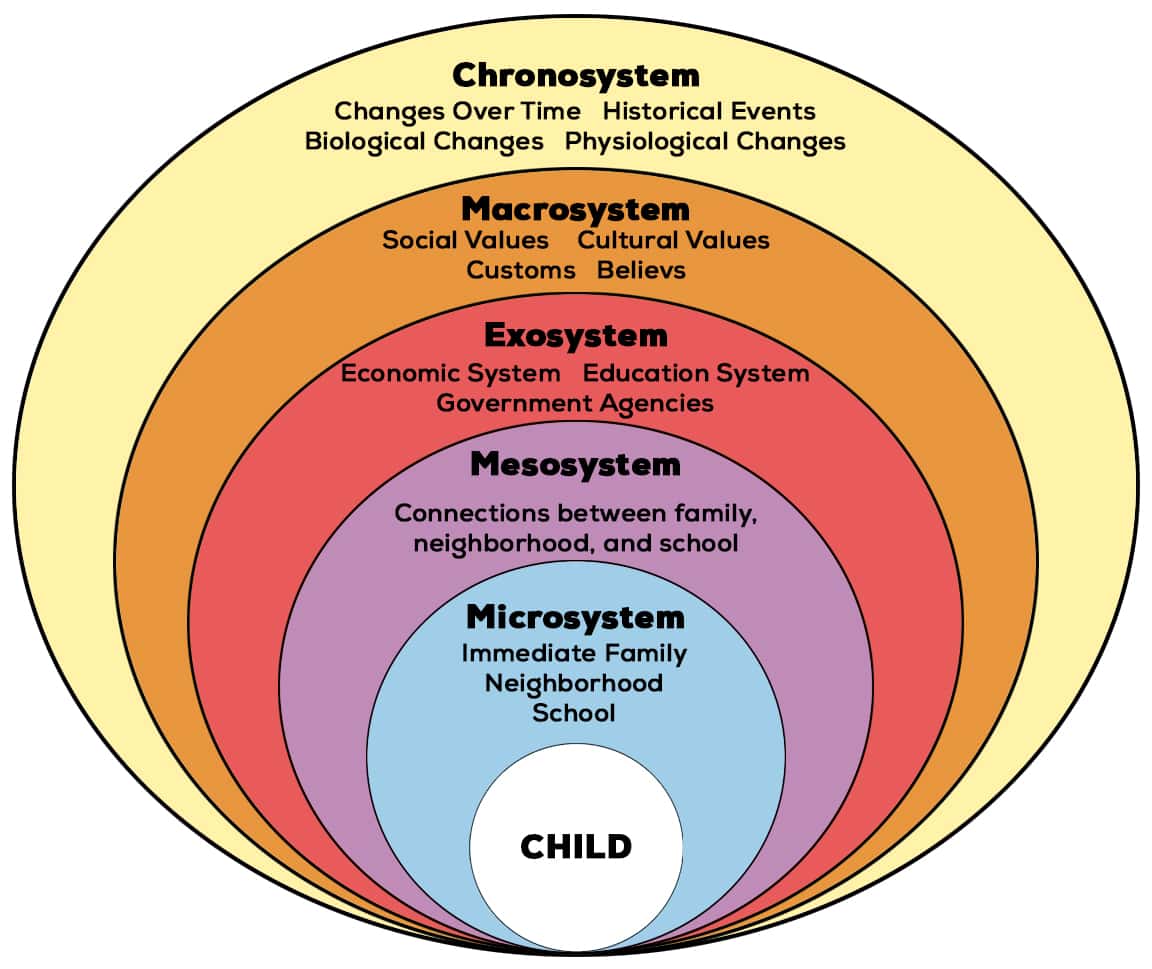

According to the ecological systems theory, a child’s development occurs within a complex system of relationships that make up his or her environment. Bronfenbrenner viewed the environment as consisting of several different layers or contexts, each nested within the other like a set of Russian dolls. Each layer interacts with the others and with the individual, thereby influencing the course of development. Unlike earlier ‘environmentalist’ approaches that focus only on the ways in which the environment impacts the individual, ecological systems theory emphasizes the dynamic, bi-directional relationship or interplay between the individual and the environment.

In his original model, Bronfenbrenner identified four layers of the environment:

The Microsystem

This is the innermost layer of the environment and refers to the interactions that occur within the individual’s immediate surroundings. In the case of babies and young infants, the microsystem consists primarily of interactions within the family. As the child grows older, the microsystem extends to include other contexts such as daycare, school, and peers within the community.

Not only are children influenced by the people in their microsystem, they also influence the behavior of the individuals around them. For example, a child with an (easy-going) temperament is likely to evoke positive feelings in his caregivers, but a child who is very irritable and difficult to soothe will likely provoke more negative reactions in his parents and may even put a strain on the marital relationship.

The Mesosystem

This layer refers to the interconnections among the microsystems in which the individual is embedded. In essence, the mesosystem is a system of microsystems. Bronfenbrenner believed that optimal development occurs when strong, supportive links exist between microsystems. For example, the quality of interactions between a child and his or her teachers plays a major role in that child’s academic performance. However, the link between the school and family is also of great importance. Children whose parents value education, take an interest in scholastic activities, and support the efforts of their teachers, are more likely to excel than those whose parents do not.

The Exosystem

This layer refers to aspects of the environment where the individual is not an active participant, but which nonetheless influence his or her development. For example, children are not a part of their parents’ work environment but may still be affected by a pay cut at the workplace or by the work schedule handed down by management. Similarly, children are not involved in developing educational policies or designing their school curriculum but these certainly have an impact on them.

The Macrosystem

This layer involves more distant influences on the individual, namely, the cultural, subcultural, and/or social class context in which the individual and all the other systems are embedded. It includes the values, laws, norms, and customs of a given culture, all of which influence the day-to-day experiences of the individual.

Bronfenbrenner also recognized that ecological systems change or evolve with the passage of time. This fact motivated him to add a temporal dimension to his theory. This fifth system became known as the chronosystem and highlights how changes over time within the other systems impact the developing person. For example, major changes within the family microsystem, such as moving to a new house, parental divorce, or the death of a parent, all have the potential to significantly alter the course of a child’s development. They may also affect the child’s development differently depending on his or her level of maturation at the time they occur (eg., infancy as opposed to adolescence).

Bronfenbrenner continued to update his model as the years passed. Whereas early researchers paid little attention to how the environment impacts child development, Bronfenbrenner believed that modern day researchers were focusing too much on the environment and not enough on the role of the individual in his or her own development. He acknowledged the role of biological maturation in steering development. For example, he showed how biologically determined characteristics (such as temperament, natural abilities, gender, and physical features) may interact with external forces to influence development. In recognition of this fact, Bronfenbrenner suggested in more recent years that his theory be renamed the bioecological model of development.

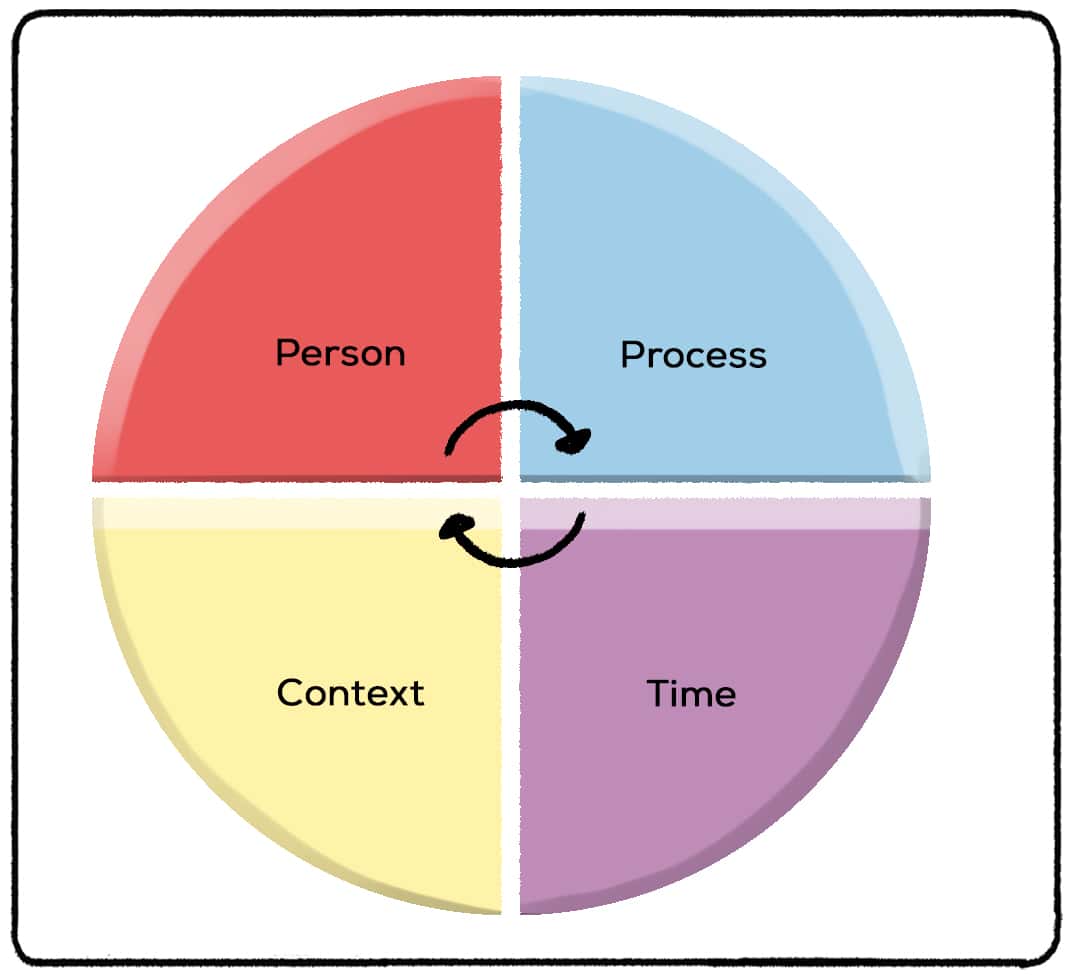

The Process-Person-Context-Time Model (PPCT)

The Process-Person-Context-Time (PPCT) model is Bronfenbrenner’s final revision to his theory. In this phase of his theory, Bronfenbrenner highlights the importance of proximal processes in development. The PPCT has four key principles that are able to interact with each other. They include:

Process - Bronfenbrenner identified proximal processes as the main drivers of development. Proximal processes involve reciprocal interactions between the developing individual and the people, symbols, or objects in his immediate environment. Two examples of proximal processes are (1) parents playing with their child, and (2) a child reading a book to learn and practice new skills.

Person - This principle emphasizes the active role that the individual and his personal characteristics play in his development. There are three types of personal characteristics: (1) demand, (2) resource, and (3) force. Demand characteristics act as immediate stimuli to another person and include factors such as the developing individual’s age, skin color, and gender. Resource characteristics are harder to observe and may include the developing individual’s past experiences, skills, intelligence, and access to social and material support. Force characteristics are related to the developing individual’s temperament, persistence, and motivation. Differences in motivation may explain why children with similar resources sometimes develop differently.

Context - Four of the five systems of the bioecological model (microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, and macrosystem) serve as the context for a person’s development.

Time - Just as there are different types of personal characteristics and different types of contexts, Bronfenbrenner divided time into three levels: micro, meso, and macro. Micro-time refers to what is occurring during a specific activity or proximal process, meso-time refers to how often specific activities take place within the developing individual’s environment over the course of days and weeks, and macro-time (the chronosystem) “focuses on the changing expectations and events in the larger society, both within and across generations.”

Applications of Bronfenbrenner’s Bioecological Model

Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological theory has been applied to a number of professional fields. Some of these include:

- Education - Teachers are encouraged to build good relationships with parents and try to understand the social and economic factors that may affect the academic performance of students. Students typically get better grades when their teachers and parents interact regularly.

- Social Work - Social workers can offer more effective services if they are aware of the cultural factors that may have shaped the development of immigrant children.

- Mental Health - Family and peer support are crucial factors for assisting individuals with mental health issues. People are also more likely to take advantage of local mental health resources if there is no societal stigma associated with going to therapy.

- Physical Health - People are less likely to become sick if they remove themselves from environments that put them at higher risk of contracting a disease. They are more likely to adopt healthier habits if they surround themselves with individuals who are health-conscious and physically active.

- Politics - Governments may resolve major problems in wider society by introducing policies and programs that benefit the family unit.

- Business - Companies may increase their earnings by designing marketing campaigns that regularly penetrate the microsystem of potential customers.

Criticisms of the Bioecological Model

There are several criticisms of Brofenbrenner’s bioecological model. One of the main criticisms is that the model is very difficult to test empirically as so many components are involved. There is also little empirical research on the specific influence of the mesosystem on child development, though it is regarded as one of the major components of the theory.

The model has also been criticized for being very broad and this may lead researchers to make broad assumptions about people that may be incorrect. For example, while the model emphasizes the powerful influence of the microsystem, many men and women who were raised in poverty-stricken or abusive households have developed into successful, healthy, and well-adjusted adults.

Another common criticism of the bioecological model is that it does not address the cognitive factors that are involved in child development. The model also fails to provide an easy-to-follow series of developmental stages as seen in other theories of child development proposed by psychologists Jean Piaget and Erik Erikson.

Urie Bronfenbrenner's Books, Awards, and Accomplishments

Bronfenbrenner authored, co-authored, and edited more than three hundred articles and fourteen books. His most influential book was published in 1979 and was titled The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. A few of his other written works are listed below:

- Two Worlds of Childhood: US and USSR, 1970

- Influencing Human Development, 1973

- Influences on Human Development, 1975

- The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design, 1979

- The State of Americans: This Generation and the Next, 1996

- Making Human Beings Human: Bioecological Perspectives on Human Development, 2005

Bronfenbrenner received honorary doctoral degrees from Penn State University, the University of Gothenburg, the Technical University of Berlin, Bank Street College of Education, Brigham Young University, and the University of Münster. He was a member of the International Society for the Study of Behavioral Development and a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the National Academy of Education, the Society for Research in Child Development, and Divisions 7, 8, 9, and 15 of the American Psychological Association.

Some of Bronfenbrenner’s other awards include:

- Chair of the 1970 White House Conference on Children (1970)

- The “Kurt Lewin Award” from the American Psychological Association (1977)

- The “Anisfield-Wolf Award” from the Cleveland Foundation (1981)

- The “Medal of Excellence” from the New York State Board of Regents (1984)

- The “G. Stanley Hall Medal” from Division 7 of the American Psychological Association (1985)

- Elected as President of Division 7 of the American Psychological Association (1986)

- The “Award for Distinguished Contributions to Psychology in the Public Interest” from the American Psychological Association (1987)

- The “Nicholas Hobbs Award” from the American Psychological Association (1987)

- The “Award for Distinguished Scientific Contributions in Child Development” from the Society for Research in Child Development (1987)

- The “James McKeen Cattell Award” from the American Psychological Society (1993)

- The "Lifetime Contribution to Developmental Psychology in the Service of Science and Society Award" from the American Psychological Association (1996)

Interestingly, the annual "Lifetime Contribution to Developmental Psychology in the Service of Science and Society Award" from the American Psychological Association was renamed as "The Bronfenbrenner Award" in Urie’s honor.

Personal Life

Urie Bronfenbenner married Liese Price in November 1942. The couple had six children—Michael, Steven, Beth, Mary, Kate, and Ann. Bronfenbrenner was a big music lover and he especially enjoyed listening to jazz, classical, and folk music. He passed his love of music on to his children.

After his retirement from academia, Bronfenbrenner became the Jacob Gould Schurman Professor Emeritus of Human Development and of Psychology in the Cornell University College of Human Ecology. Modern day researchers have commented that before Bronfenbrenner proposed his bioecological theory, it was not uncommon for child psychologists to study children, sociologists to study the family unit, anthropologists to study society, economists to study the economy, and political scientists to study the societal impact of policies and laws. However, Bronfenbrenner’s work shattered barriers and built bridges between the social sciences.

Urie Bronfenbrenner passed away on September 25, 2005 in Ithaca, New York. He was 88 years old. Medical reports indicate that Bronfenbrenner died after experiencing complications due to diabetes. He is survived by his six children, thirteen grandchildren, and a great-granddaughter.

References

Association for Psychological Science. (2005). Obituary. Retrieved from https://www.psychologicalscience.org/observer/in-appreciation-urie-bronfenbrenner

Bronfenbrenner, U. (n.d.) Urie Bronfenbrenner curriculum vitae. Retrieved from https://www.srcd.org/sites/default/files/file-attachments/bronfenbrenner_urie_cv.pdf

Eriksson, M., Ghazinour, M. & Hammarström, A. (2018). Different uses of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory in public mental health research: What is their value for guiding public mental health policy and practice? Social Theory and Health, 16, 414–433.

Gray, C., & Macblain, S. (2012). Learning theories in childhood. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Hayes, N., O’Toole, L., & Halpenny, A. M. (2017). Introducing Bronfenbrenner: A guide for practitioners and students in early years education. New York: Routledge.

Rosa, E. M., & Tudge, J. (2013). Urie Bronfenbrenner’s theory of human development: Its evolution from ecology to bioecology. Journal of Family Therapy and Review, 5, 243-258.

Smart, J. (2012). Disability across the developmental lifespan: For the rehabilitation counselor. New York: Springer Publishing Company.

Urie Bronfenbrenner. (n.d.) In Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Urie-Bronfenbrenner

Urie Bronfenbrenner. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://bctr.cornell.edu/about-us/urie-bronfenbrenner