A 2002 empirical survey published by Review of General Psychology rated Asch as the 41st most eminent psychologist of the 20th century.

Who Is Solomon Asch?

Solomon Asch was a Polish American psychologist who specialized in gestalt psychology and pioneered social psychology. He conducted groundbreaking research on a number of topics, including how people form impressions of others and how prestige may influence judgements. Asch is best known for his work on group pressure and conformity.

Solomon Asch's Childhood

Solomon Elliott Asch was born on September 14, 1907 in Warsaw, Poland. He was raised in the small neighbouring town of Lowicz in a large Jewish family. Asch described his childhood as “a time of great anxieties, big fears, [and] grave dangers.” This state of affairs was due in large part to the outbreak of the first World War and to instances of anti-Semitism in Eastern Europe.

An experience Asch had as a child would remain with him into his adult life and later influence his studies on group pressure and conformity. At about age seven, during the celebration of the Jewish Passover, a cup of wine was placed at an empty spot at the table. A curious Asch was told that the wine was for the prophet Elijah. According to his uncle, the prophet visited each Jewish home on the Passover and would take a sip of wine from the cup left out for him. Fascinated, Asch kept watching the cup and although the level of the wine never declined, there came a point when it seemed to him that “perhaps it did go down a little!” The group pressure from other members of the family caused him to think that the level of wine had indeed changed.

As a boy, Asch was naturally shy and introverted. He once said that it would have been easier for him to not breathe than to not be shy. In 1920, when he was 13 years of age, his family migrated to the United States. They found a home on New York’s Lower East Side, where they were surrounded by many other Jewish, Irish, and Italian immigrants.

Early Schooling

Asch was placed in the 6th grade at the neighbourhood public school but initially had difficulty learning English. He eventually mastered the language through extensive reading of Charles Dickens novels. About two years after arriving in the United States, he was admitted to Townsend Harris Hall, a small elite high school for academically advanced males.

Educational Background

After completing high school, Asch attended the City College of New York, where he studied literature and science. He received his bachelor of science degree in 1928 at the age of 21. He first learned about psychology toward the end of his undergraduate career and his interest was piqued. However, his knowledge of psychology was quite limited, derived mainly from reading works by William James and a few philosophers. Some of his initial assumptions about the field were also incorrect and in his own words, one could “almost say that [he] came into psychology by mistake.”

Despite his limited knowledge of the field, Asch went on to pursue graduate studies in psychology at Columbia University. He also had an interest in anthropology and spent a summer observing children in the Hopi culture to determine how they became assimilated into that culture. He was awarded his masters degree in 1930, followed by a doctoral degree in 1932.

Study of Gesalt Theory

During his time at Columbia, Asch received his first exposure to Gestalt psychology and the ideas associated with this school of thought appealed to him greatly. He was particularly drawn to the work of Gestalt theorist Max Wertheimer, who emigrated to the United States from Europe in 1933. Upon learning of his arrival in the United States, Asch actively sought out Wertheimer and despite not studying with him, got to know him very well. Wertheimer became Asch’s most significant mentor and Asch would later extend the principles of Gestalt psychology to social psychology and to the study of thought, perception, and behavior.

Asch believed that it is necessary to study human beings both as individuals and as members of social groups if human nature is to be properly understood. He recognized that individuals could influence group behavior, and groups could influence the behavior of individuals. According to Asch, social acts must be investigated in their natural setting. This is crucial because studying social behaviors in isolation would rob the behaviors of all their meaning.

Asch accepted a teaching position at Brooklyn College in 1932. In 1943, he was appointed chair of psychology at the New School for Social Research, replacing his mentor, Max Wertheimer, who died that year. Asch remained at the New School until 1947 when he moved to Swarthmore College in Philadelphia. At Swarthmore, Asch developed a close relationship with renowned Gestalt psychologist, Wolfgang Kohler, who was also on the faculty there.

Working With Stanley Milgram

During his time at Swarthmore, he also served for two years (1958-1960) as a member of Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study. There, Stanley Milgram, who later became a prominent psychologist, worked as his research assistant. It was also during his time at Swarthmore that Asch conducted his famous experimental studies on conformity.

In 1966, Asch left Swarthmore to help establish the Institute for Cognitive Studies at Rutgers University in New Jersey. He served as the head of the Institute from the time of its inception until 1972 when he accepted a position at the University of Pennsylvania (UPenn) as Professor of Psychology. Apart from a year spent at the Center for the Advanced Study of the Behavioral Sciences in Stanford, Asch remained at UPenn until his retirement in 1979. He was Professor Emeritus of Psychology until 1996.

Asch’s Experiments on Perception

In the 1940s, Solomon Asch and Herman Witkin investigated how a person’s visual frame of reference may impact his or her perception of an upright object. At the time, the popular belief was that gravity receptors in the body were the primary factors that helped people to decide whether a particular direction was vertical or horizontal. With behaviorism being a dominant force at the time, much emphasis was placed on factors that could be seen and measured, such as a person’s posture and physical orientation. Asch and Witkin’s experiments challenged these behavioral explanations of how people perceive space and direction.

In one of their perception studies, Asch and Witkin allowed participants to view the research lab through a cardboard tube. Unknown to the participants, the cardboard tube was actually aimed at a reflection of the lab, and this reflected image was tilted up to 30 degrees from true vertical alignment. The participants were given a rod and asked to position it so that it maintained alignment with the true vertical. The results of the experiment showed that the participants were more likely to tilt the rod according to the tilt of the reflected image, rather than keep it aligned to the true vertical.

Results of Asch's Line Perception Studies

These perception experiments showed that visual information plays a major role in determining how people orient themselves and other objects in space. If postural or physical factors were the primary tools for orientation as behaviorists claimed, more participants would have kept the rod aligned with the true vertical regardless of the tilted image they were shown.

Impression Formation

A common behaviorist belief in the 1940s and 1950s was that a person could be completely understood by studying the different parts or elements that make up that person. Asch rejected this line of thinking in favor of the gestalt principle that people were more than the sum of their parts. To help determine which approach was more accurate, Asch designed a series of clever experiments to reveal how individuals form impressions of other people.

In one experiment, Asch gave two groups of people a list of personality traits. The lists for both groups were very similar, they only differed by one trait.

For example:

Group 1 - tough, determined, sociable, industrious, intelligent, skillful

Group 2 - tender, determined, sociable, industrious, intelligent, skillful

OR

Group 1 - skillful, intelligent, practical, cold, industrious, cautious

Group 2 - skillful, intelligent, practical, warm, industrious, cautious

Asch then asked the participants to write a brief description of the impression they formed about the imaginary person who had these traits. He also gave the participants a checklist of word pairs that contained opposites (such as → kind/mean, generous/ungenerous, etc) and asked them to indicate which trait on the checklist matched the person they had in their mind.

Results of Impression Formation Work

Asch discovered that participants who were given a list with the words “tender” or “warm” were more likely to have a positive impression of the imaginary person than participants who were given a list with “tough” or “cold.” The written descriptions also showed that other personality traits (such as “determined” and “cautious”) were viewed in a more positive light if the person was also described as “tender” or “warm.” As traits such as tender, tough, warm, and cold seemed to affect how other qualities are perceived, Asch referred to them as “central” characteristics. Other traits that did not have a major impact on impression formation were called “peripheral” characteristics.

While behaviorists view people as a complete collection of parts, these results showed that personality traits are not isolated units that can simply be added together. Rather, Asch’s findings showed that it is possible for traits to interact with each other, and this interaction may affect the way people are perceived by onlookers.

In another experiment, Asch investigated whether or not impression formation may be affected by the order in which items are presented.

Participants were given one of the following lists:

- Intelligent, industrious, impulsive, critical, stubborn, envious

- Envious, stubborn, critical, impulsive, industrious, intelligent

List 1 begins with a positive trait and ends with a negative trait, while list 2 begins with a negative trait and ends with a positive trait. The words in each list are exactly the same, the order has simply been reversed. Asch found that participants viewed the imaginary person in list 1 as a positive, capable person who has a few shortcomings. On the other hand, participants viewed the imaginary person in list two as a negative person with serious problems.

The results showed that the order in which personality traits are presented can impact the impression individuals form of other people. The results also undermined the behaviorist view that people are simply the sum of their parts. If that view was correct, participants who were given list 1 and participants who were given list 2 would have formed similar impressions about the imaginary person because all the “parts” are exactly the same.

Prestige Suggestion

As World War II unfolded in the 1940s, many psychologists became interested in propaganda and indoctrination. How could you make people believe that it was in their best interest to sacrifice for the war effort? Psychologists had noticed long before that people were more likely to agree with a statement if it was given by a speaker who had a measure of prestige. The popular belief at the time was that the greater the prestige a speaker or writer had, the more he or she could influence the population.

Asch disagreed with this simplistic explanation. He believed people were doing more than just blindly accepting a message based on the identity of the speaker. He suggested that people may change the way they interpret a message if they know who the message is from.

Jefferson vs. Lenin Study

In one of his experiments, Asch shared the following quotation with some American students: “I hold it that a little rebellion, now and then, is a good thing, and as necessary in the political world as storms are in the physical." Some of the students were told that the statement was made by former American president Thomas Jefferson, others were told that the statement was made by Vladimir Lenin—former head of the Sovient and a well-known communist. The students were also asked to write what the quote meant to them.

Asch found that American students were more likely to agree with the quote when it was attributed to Jefferson than Lenin. The meaning of the quote also changed, depending on who the students thought the author was. When the quote was attributed to Jefferson, the “little rebellion” was believed to be related purely to politics. When the quote was attributed to Lenin, it was interpreted to mean a little blood had to be spilt.

The Asch Conformity Experiments

In 1951, Asch conducted his classic conformity experiments. He wanted to investigate how social pressure impacts people’s decision-making and whether (1) the size of the group, or (2) the unanimity of the group was more important for influencing opinion.

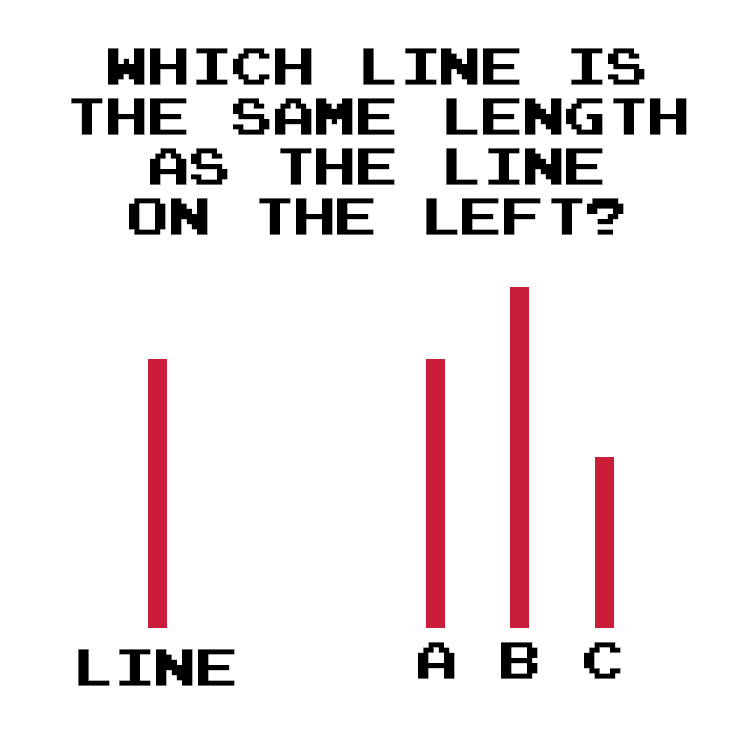

Asch invited 50 male Swarthmore students to take part in a “vision experiment.” Each participant was placed in a room with 5-7 confederates (people who were secretly working with Asch). The group was first shown a card with a line on it, then they were shown a second card with three lines labeled A, B, and C. Each person was then asked to choose which line on the second card matched the line on the first card. The real participant always gave his answer last or second to last.

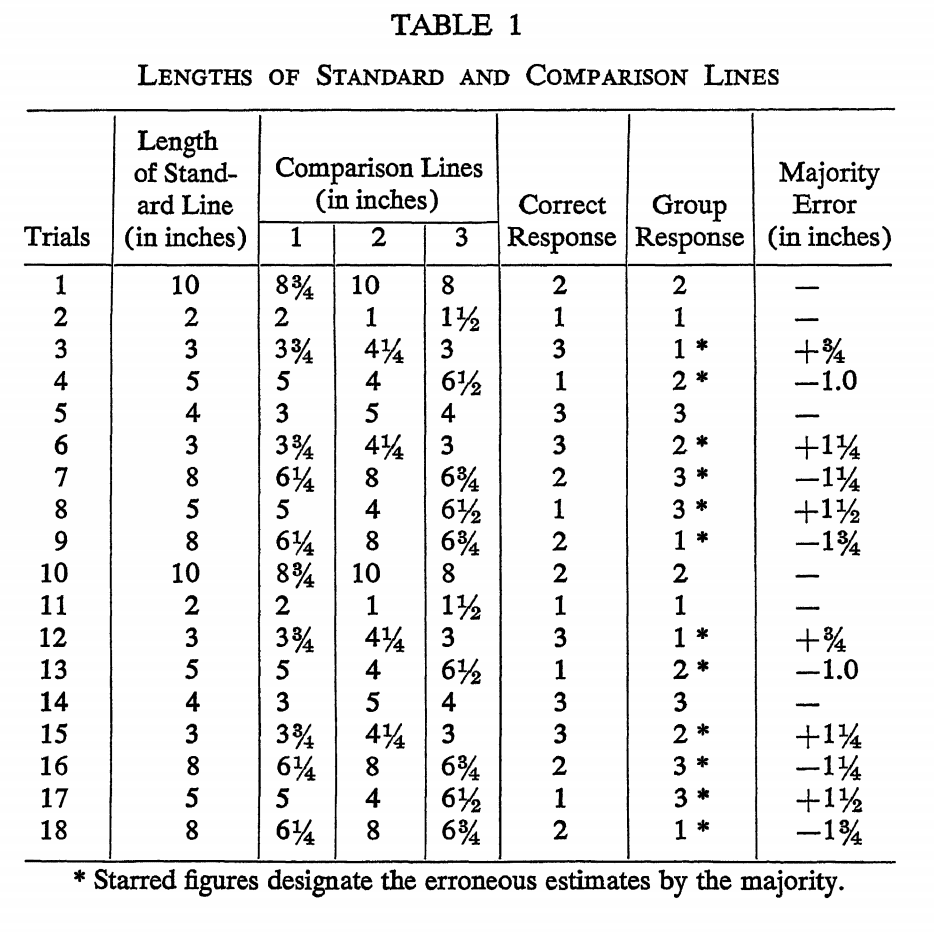

There were eighteen rounds or trials in total and the correct answer for each trial was very obvious. Unknown to the participant, the confederates were instructed to answer incorrectly in twelve specific trials. These twelve trials were called the “critical trials.” Asch also set up a control group where only the participant was present.

During the first two rounds, all the confederates answered correctly and this helped to put the participant at ease. However, after the fourth round, the confederates all gave the same wrong answer whenever they got to a critical trial. They gave these wrong answers loudly and confidently. Asch then waited to see if the participant would conform to group pressure by giving the same incorrect answer as the confederates.

Results of Asch's Conformity Experiments

The results of the experiment showed that 25% of participants were able to withstand all forms of group pressure and give the correct answer in each trial. However, 75% of participants conformed to group pressure at least once. In the control group, less than 1% of participants answered incorrectly.

Why did so many participants conform at least once to the majority view when they could see the correct answer for themselves? After the experiment, some of the participants explained that they did not want to stand out or be ridiculed for their answers. Other participants said they actually thought the majority view was correct. Although they could see the correct answer, they convinced themselves that perhaps the line was just a little too short and so they went with the group’s answer. Asch concluded that there are two major reasons people conform:

They want to appear normal and fit in with everyone else in the group (this is called normative influence)

They think the group is better informed than they are (this is called informational influence)

Asch found that conformity was more likely to occur if there were three or more confederates who all gave the same wrong answer. However, if one confederate gave the correct answer while the other confederates answered incorrectly, the participant was much less likely to conform. In later experiments, he showed that conformity increases when (1) the task at hand is more difficult, (2) the other members of the group have a higher social status, and (3) the participant is asked to respond publicly.

Applications of Asch’s Theories

Social conformity is found in many aspects of everyday life. Civilized society is built upon people’s willingness to conform to certain rules or standards that help to maintain order and promote progress. For example, people conform to social standards of wearing clothing in public and driving in a particular lane on the road. However, social pressure may also be applied to other fields such as:

Politics

Residents who display political yard signs may influence other residents in their community to vote for a specific political party

Marketing

Companies may increase sales by using stats to show that most people in the neighborhood are using a specific product or service

Healthcare

People who want to improve their health may be encouraged to surround themselves with individuals who have healthy habits such as exercising regularly and eating a healthy diet

Parenting

Parents may influence the behaviors their children develop by monitoring the friends they keep

Military

New recruits are influenced to shave their head, develop combat skills, and follow orders if they want to fit in with the group

Education

Schools maintain order by ensuring that new students conform to certain existing standards. New students may be influenced to wear a uniform or respond to specific bells when they observe the behavior of other students.

Criticisms of Asch’s Theories

One major criticism of Asch’s conformity experiments is that his sample was not representative of the general public. His participants were all young male students who attended Swarthmore College. Consequently, his results may not be applicable to females or older people.

A second issue is that the study has low ecological validity as the results may not be applicable to real-life scenarios that involve conformity. Asch ensured that the participants were able to identify the correct answer in each trial. However, people in real-life situations of conformity may be unsure what the correct decision is.

Some critics have claimed that Asch’s experiments say more about American culture than conformity. Studies conducted in other countries show that the level of conformity may change depending on whether a country prioritizes individualism or collectivism. Other critics argue that participants did not have a desire to conform to the rest of the group, but simply wanted to avoid unnecessary conflict. Some participants reported that they agreed with the group because they did not want to “spoil” the results.

Solomon Asch's Contributions to Psychology: Books, Awards, and Accomplishments

Asch authored a number of landmark articles that helped to shape the field of social psychology. However, he despised the “publish or perish” approach that was practiced in American academia. In 1952, he published his research findings in the book Social Psychology.

A few of Asch’s other awards and accomplishments include:

Fellow of the Guggenheim Foundation, 1941-1942 and 1943-1944

Member of the Institute for Advanced Study, 1958-1960 and 1970

Senior Fellow of the U.S. Public Health Service, 1959-1960

Awarded the Nicholas Murray Butler Medal from Columbia University, 1962

Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 1965

Received the Distinguished Scientific Contribution Award from the American Psychological Association, 1967

Fellow of the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, 1976-77

Personal Life

Asch married Florence Miller in 1930 and the two enjoyed a long and pleasant marriage. Asch and Florence met at a library and although they lived just a few blocks apart, they wrote to each other constantly during their courtship. They had a son, Peter, in 1937, who later became a Professor of Economics at Rutgers University.

Asch, who was affectionately called Shlaym by his friends, died on February 20, 1996, at his home in Haverford, Pennsylvania. He was 88 years of age. He was survived by his wife, two grandsons, a granddaughter, and a great-grandson. His son, Peter, predeceased him in 1990.

References

Asch, S. E., & Witkin, H. A. (1948). Studies in space orientation: I. Perception of the upright with displaced visual fields. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 38(3), 325–337.

Ceraso, J., Gruber, H., & Rock, I. (2014). On Solomon Asch. In I. Rock (Ed.), The legacy of Solomon Asch: Essays in cognition and social psychology. New York: Psychology Press.

Death of Solomon Asch. (1996). Retrieved from https://almanac.upenn.edu/archive/v42/n23/asch.html

King, D. B., Viney, W., & Woody, W. D. (2013). History of psychology: Ideas and context (5th ed.). New York: Routledge.

Korn, J. H. (1997). Illusions of reality: A history of deception in social psychology. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Sheehy, N. (2004). Fifty key thinkers in psychology. New York: Routledge.

Stout, D. (1996). Solomon Asch is dead at 88; a leading social psychologist. Retrieved from

https://www.nytimes.com/1996/02/29/us/solomon-asch-is-dead-at-88-a-leading-social-psychologist.html

The Solomon Asch Center for Study of Ethnopolitical Conflict. (n.d.). Solomon E. Asch 1907-1996. Retrieved from http://www.brynmawr.edu/aschcenter/about/solomon.htm