Have you ever watched a video or seen a GIF that was just...oddly satisfying? Or maybe you can relate to the episode of The Office when they wait patiently for the DVD graphic to fit perfectly in the bottom corner of the screen. Why does it feel so soothing when things fall into place or fit just right?

The answer has to do with the way our minds work - or at least this is what Gestalt psychology says. Gestalt Principles explain how we see images and why certain images are soothing or satisfying.

What Is Gestalt Psychology?

The Gestalt Principles of Grouping are a small part of the larger Gestalt Psychology. Gestalt Psychology was first proposed by Austrian and German psychologists Max Wertheimer, Wolfgang Köhler, and Kurt Koffka. No, “Gestalt” is not the name of a psychologist who contributed to this work. In German, Gestalt translates to form.

Gestalt psychologists looks at the way that our mind recognizes forms and patterns. After all, we have a lot to take in. Think about everything that you can see around you, right now. This includes the patterns on the wall, the details in the floor, and any other individual objects that you could turn your focus to at any given moment. In order to recognize all of these things, we do have to intentionally turn our focus to them. That’s because our mind defaults to grouping objects or elements together to form patterns or categories.

These principles have served as guidelines for designers, marketers, and anyone who wants to build a satisfying image. After all, if we don’t want to look at a product’s packaging or website, we’re probably not interested in buying it.

Law of Prägnanz

All of the principles of grouping speak to the Law of Prägnanz. (This is also known as the Law of Good Gestalt.) Prägnanz is also a German word. It translates to “pithiness,” or “orderliness.” This law suggests that the mind looks for orderliness or simplicity when looking at images. It’s more simple to see one whole image rather than the sum of its parts. That’s why, when we look at an image of a book, we see one item. We don’t see an item with a cover, back cover, and over 100 individual pages.

The principles of grouping break down how the mind groups, categorizes, or “follows” elements to create a more simple or orderly image. Remember, this is the work of the mind. It has nothing to do with our eyesight.

Principles of Grouping

Originally, the principles of grouping were called the laws of grouping. Over time, as more research has been done, they have been renamed as the principles of grouping.

Not every list you see will include all of these principles. Some lists will include more principles that are not seen here. Many will list the Law of Prägnanz as one of the principles of grouping, rather than an overarching principle that explains the others. A few of these principles may sound repetitive, or like “common sense.” But the following principles are meant to give you a basic understanding of grouping and how it affects our ability to perceive what we are looking at.

Some of the principles of grouping include:

- Figure-ground

- Similarity

- Proximity

- Common fate

- Continuity

- Closure

- Symmetry

Figure-Ground

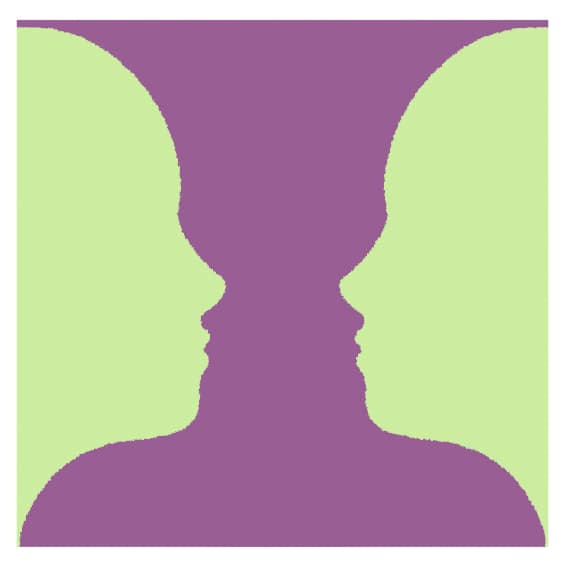

Tell me if this image sounds familiar to you. You’re looking at a black and white image. Maybe you see a vase in the middle of the image. Or, maybe you see two faces. Either way, you see either one of these images first. It takes a moment to adjust your perspective and see the other.

This image is known as Rubin’s Vase, or The “Two Face, One Vase” illusion. It’s a classic example of the Figure-Ground principle within Gestalt theory.

The idea is that the mind categorizes images by whether they are in the foreground or the background. We direct our attention to the foreground, leaving the background behind. It’s only when we pay attention to the background that we see the “full picture.”

If your mind quickly registered the vase, you recognized it as the foreground, and you probably disregarded the two faces altogether. The same goes for recognizing the faces first.

Similarity

The second principle states that we tend to group things that are similar together. When our mind makes these groups, we make similar assumptions about the group and all of the objects in it.

It is interesting to see how this principle plays out when multiple similarities are present. For example, the game Set asks you to find a set of cards of three cards. The cards have one of three shapes, one of three colors, or one-three shapes. The goal of the game is to find a set of cards that are either similar or all different in each area (shape, color, number.)

It’s easier to recognize cards that are the same color. The real brainpower comes in when distinguishing numbers and shapes.

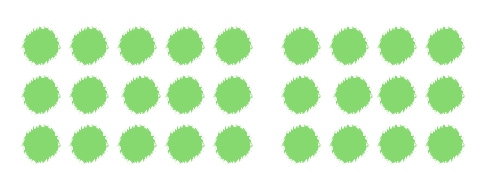

Color plays a big role in the similarity principle. But if all the images in one group are the same color, our mind looks for different categories (shape, size, distance between each element or image) to organize what is in front of us.

Take the homepage of hubspot.com. The background of each “section” helps us organize all of the website’s information. The header, most recent announcement, list of features, statistics are all presented with different color backgrounds. This is intentional. If the entire front page had one background, it would be harder for us to explore the website and take in the information.

Proximity

I mentioned just a moment ago that the distance between each element plays into how we perceive the overall image. This is the principle of proximity.

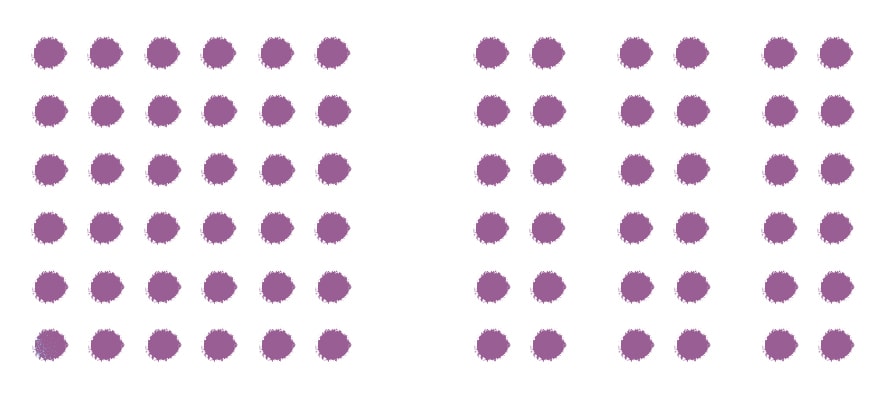

When we see elements located close together, our mind puts these elements in a group. Take this image of 72 dots. When we look at this image, we don’t see 72 individual dots. We see 2-5 groups of dots. The first group is the big square of 36 dots, placed all together at equal distances. Farther away is the 12 dots placed together at the same distance. Farther away is another 12 dots. So on and so forth.

Common Region

What about this photo of 27 dots? They’re all equally spaced apart, yet our minds separate them into two groups. This can be explained by the Common Region principle. When a set of elements is enclosed, we automatically separate it from the set that is not enclosed.

Common Fate

Don’t confuse Common Region with Common Fate. This principle takes a slightly different approach to how we categorize elements. Common Fate only applies to moving elements. If a set of elements are moving in the same direction, they are separated from the rest of the elements in the overall image. Some psychologists believe that this principle came out of evolutionary needs. A camouflaged predator probably won’t be recognized if it’s staying still. But once it starts to run, you’re more likely to spot it.

It’s important to note that Common Fate was not included in the original principles of grouping. These principles have been redefined over time, and new principles have been added to the list.

Continuity

The above principles speak to the idea that our mind categorizes elements to make things easier for ourselves. It’s easier to recognize two groups of dots than it is to recognize 72 individual dots. But let’s continue to talk about things that are “moving.”

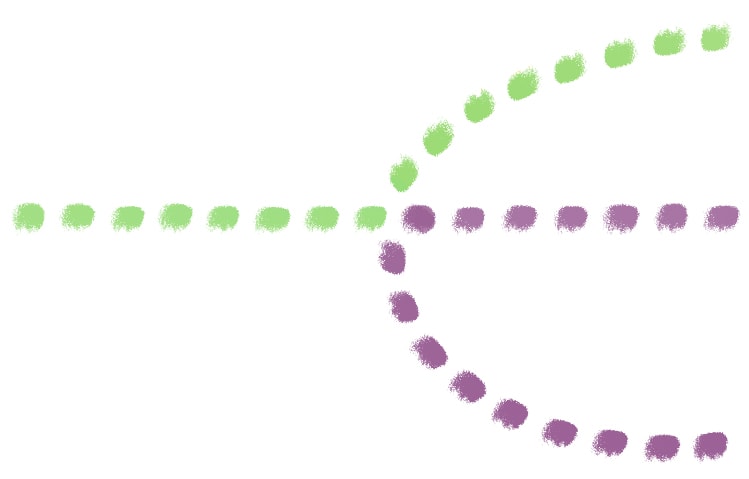

Our eyes move throughout an image based on the placement of the elements and the “visual flow.” The mind instructs the eyes to follow the easiest visual flow, even if the flow is interrupted by other elements or a difference in those elements. When there are interruptions, we put them in a different category.

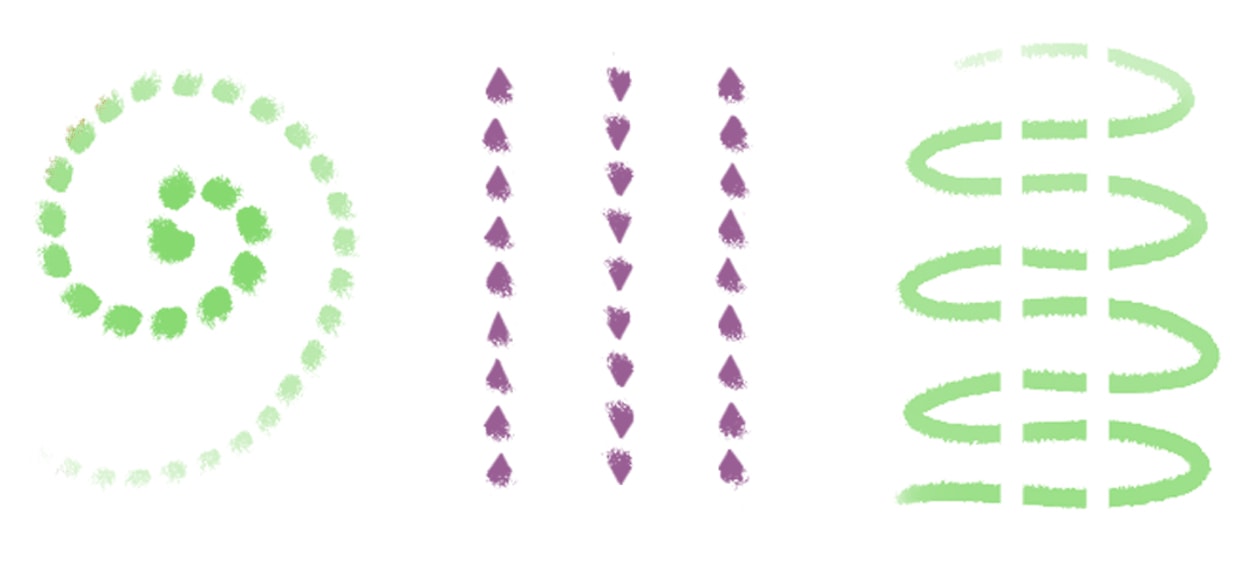

Take a look at the triangles at the center of this image. Our mind automatically categorizes them into three rows of triangles, despite their similar shape and size. Why? They are going in “different directions,” and our mind has to follow three different flows. So we perceive them as three separate lines.

Or look at this image. The mind recognizes the curved line first, regardless of the fact that changes color halfway through. The “visual flow” of following the straight line or curved line is just easier for our minds to observe.

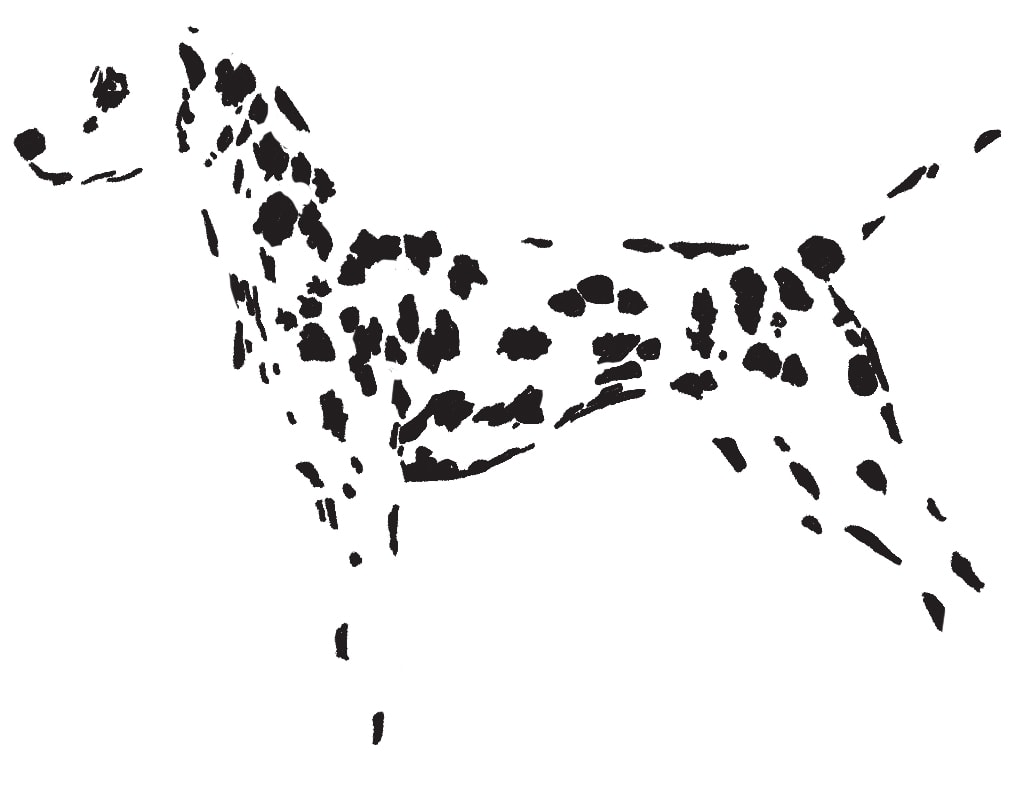

Closure

The principle of closure is key to understanding Gestalt theory. Gestalt theory overall states that the mind seeks to perceive a whole image, rather than the sum of its parts. How do we do that? We may “close the gaps” to give ourselves a single shape or image. This is the principle of closure.

Take a look at this image. Your mind might automatically tell you that this is a soccer ball instead of a collection of pentagons. (Or a football if you’re not American.)

Here’s another example. Do you see a set of spots, or a Dalmatian?

Of course, if you’ve never seen a soccer ball or a Dalmatian before, you might not come to these conclusions. But to understand that concept, we have to look into different principles or concepts in psychology.

Symmetry

Another way that the mind groups elements together is by looking for symmetry. If the mind sees two symmetrical items, it will group them together as one image. This poster is a great example of symmetry in action. The bike wheel and manhole cover are clearly two separate items. But due to their symmetry, we perceive the image as one unified circle.

All the Gestalt Principles At One Time!

Need to tell the difference between all seven Gestalt principles? Check out this infographic from Reddit user LindseyBetz!

Examples Of Gestalt Principles

- Proximity: Objects that are close to one another are perceived as a group. For example, when you see a group of people standing close together at a bus stop, you assume they're all waiting for the bus, even if they're not together.

- Similarity: Objects that look similar are perceived as being in the same group. For instance, in a sea of red apples, a green apple stands out.

- Closure: Our minds tend to "close" gaps in an image to create a full, complete picture. For example, if part of a circle is obscured, we still perceive it as a circle.

- Continuity: Lines are seen as following the smoothest path. For instance, if two lines cross each other, we tend to see them as two continuous lines rather than four separate lines.

- Figure-Ground: Our eyes separate elements based on contrast, seeing objects as either in the foreground (figure) or the background (ground). For example, in a silhouette, we can distinguish a person's profile against the sky.

- Symmetry & Order: Symmetrical elements are perceived as belonging together regardless of their distance from each other. For instance, symmetrical vases on opposite ends of a shelf are seen as a pair.

- Common Fate: Objects moving in the same direction are perceived as a group. For example, a flock of birds flying together is seen as one unit.

- Past Experience: We perceive objects based on our past experiences and knowledge. For instance, even if a child's drawing of a cat isn't accurate, we can still recognize it as a cat because of our previous experiences with cats.

- Connectedness: Elements that are connected by other elements, like a line, are seen as a group. For example, dots connected by a line are seen as a single unit.

- Common Region: Elements located within the same closed region (like a border) are perceived as a group. For instance, words inside a boxed area on a website are seen as related content.