Why do people behave the way that they do? It’s an age-old question that psychologists have been studying for centuries. But you don’t have to be working in a research lab to ask yourself that question. In fact, we try to answer this question every single day. You might try to explain someone’s behavior at the bus stop, at work, or while you’re watching the news.

In addition to understanding human behavior, psychologists want to understand how we explain the behaviors of others and ourselves. The larger theory exploring this idea, Attribution Theory, is an umbrella with many other ideas, theories, and models below it. Here, we’re going to talk about one of the most well-known models within Attribution Theory: Kelley’s Covariation Model.

What Is Kelley's Covariation Model?

“Covariation” is a term that basically means that two or more variables are present. Kelley’s covariation model takes a look at how we attribute behaviors based on multiple variables or pieces of information. The conclusion that we make, according to Kelley’s Covariation Model, is that of situational or dispositional attribution.

The major assumption of Kelley's Covariation Theory is that as people gather information to make judgements, they attribute behaviors with logic and rationality.

Attribution Theory

Again, attribution theory looks at one big idea: what we attribute to other people’s behaviors. In other words, how do we determine the cause of another person’s behavior? Do we think the guy who gave us side-eye on the bus is a jerk, or is he just having a bad day? Is the guy who gave us side-eye on the bus a jerk, or did we do something to offend him?

As a whole, attribution looks at the information that we gather in order to come to these conclusions. The man on the bus giving us side-eye: does he look like a jerk? Have we seen him giving side-eye to us before? Does he appear to be giving side-eye to other people? Is it a rainy day? Is the bus driver playing music that is annoying everyone on the bus? What are other people doing? Attribution theory attempts to classify, categorize, and understand all of these factors and put together ideas about what we may name as the cause of someone else’s behavior.

Dispositional vs. Situational Attribution

In general, psychologists believe that we attribute someone’s behavior to one of two things. This is known as the distinction between dispositional attribution and situational attribution.

Dispositional attribution is the process in which we blame another person’s behavior on their disposition, or their character. For example, we may see the man on the bus giving us side-eye and think, “That guy is just rude.” That is part of his character. If we saw him curse out another passenger or fail to tip at a restaurant, this may enforce the dispositional attribution and enforce the idea that the man just has bad character traits.

Situational attribution is the process in which we blame another person’s behavior on external factors, or the situation. There are a number of reasons why the man could be giving side-eye that have nothing to do with his character. Maybe he has mistaken you for someone who was rude to him before. Maybe he was just having a bad day. Maybe the music on the bus is too loud and he is hangry. None of these things put a stain on the man’s character. We may think that he is probably a nice guy who was behaving as a response to whatever is going on around him.

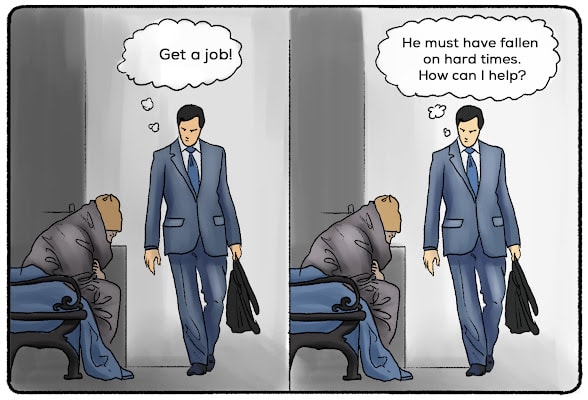

You can probably think of a situation in which you attributed someone’s behavior to their disposition or to the outside situation. The photo above shows how easily we could make a judgement using dispositional (left) or situational (right) attribution.

Maybe you have found yourself attributing the same behavior to internal or external factors, depending on the person who is displaying the behavior. You may excuse your friend getting too drunk at the bar because they are having a bad day, but judge the person next to them who is similarly getting too drunk and believe that they have a drinking problem or make bad choices.

We do this all the time. It’s not necessarily bad to come to different conclusions regarding the same behavior or different behaviors displayed by the same person.

So why do we do it? Why do we come to a different conclusion about two friends behaving in the same way? This is what Kelley’s Covariation Model attempts to explain.

Kelley's Covariation Model

Harold Kelley is a social psychologist who spent much of his career looking at how groups interact with each other. He is best known for this covariation model, and this model is also one of the most well-known ideas within the larger study of attribution theory.

When do we decide that a behavior comes from someone’s character, and when do we decide that the behavior is just an anomaly, influenced by external factors?

Kelley believed that we rely on three factors: consensus, distinctiveness, and consistency. Based on what the “data” tell us about these factors, we come to a conclusion. In a way, Kelley’s Covariation Model suggests that we are all psychologists, using data and research to come to conclusions about human behavior.

Consensus

The first factor is consensus. How does a person behave in relation to the people around them? If their friends jumped off a bridge, would they follow, or would they stray from the pack? Based on the answer, we attribute a high consensus or low consensus to the behavior.

Here’s an example. You’re at a bar on a date and everyone around you is ordering tequila shots. If your date also orders a tequila shot, consensus is high. If your date decides that they are going to stick to water, consensus is low.

Distinctiveness

Next is distinctiveness. How distinctive is the behavior to the situation? Is it considered “normal” or customary for the person to perform that behavior in the situation? Whether a behavior is distinctive may also depend on the location where the behavior is performed or the culture of where you are.

Let’s go back to the tequila shot example. If you notice that your date tends to order tequila shots whenever you’re in a bar on a Friday night, distinctiveness is low. If the date typically sticks to non-alcoholic beverages at a bar but that night decides to order a tequila shot, distinctiveness is high.

Consistency

Last but not least is consistency. How often is this behavior performed over time, regardless of the situation? Holidays, special events, or celebratory occasions may throw off someone’s consistency. We all know someone who might deviate from their normal behavior because it’s a special time of year or because relatives are making their annual visit.

If you continue to date the person from this example and you notice that they are always the first person to recommend shots at parties, bars, or weddings, consistency is high. If they tend to stick to non-alcoholic beverages, but decide to take shots for special occasions, consistency is low.

Kelley's Covariation Model Examples

So we gather all of this information as we observe our friends, neighbors, colleagues, or new romantic partners. How do we come to a conclusion?

In some cases, one or two of these factors tell us all we need to know to come to a conclusion. If someone acts inconsistently, we are likely to attribute their behavior to external factors. They are getting more rowdy than normal because they are at a wedding; they always tip really well because it is just in their nature to be generous.

Other psychologists have built onto this theory, putting together combinations that lead to one of two (or three) conclusions:

Low Consensus, Low Distinctiveness, and High Consistency lead us to come to the conclusion that the behavior has a Dispositional Attribution.

High Consensus, High Distinctiveness, and Low Consistency lead us to come to the conclusion that the behavior has a Situational Attribution.

What If We Need More Information?

The whole idea behind the Covariation Model is that we have multiple points of data to form a correlation and come to a conclusion. But what if we don’t know someone that well? What if we’re on a first date, and trying to determine whether the date ordering a tequila shot was a sign of their tendency to party or a bundle of nerves?

Kelley believes that when we don’t have enough information, we rely on past experience. What do we know about other first dates who have ordered tequila shots? How have we behaved on first dates? What else has this person said or done that could explain their behavior? We look for multiple necessary causes or multiple sufficient causes.

This Is Just a Theory

While Kelley’s Covariation Model can shine a light on how we assign causes to another person’s behavior, it’s not perfect. We may jump to conclusions without a lot of data points. We may choose to ignore certain data points in order to reach a conclusion that is favorable to us. We may make assumptions about past behaviors or use past experiences that don’t exactly apply to the situation we are analyzing. All of these things can happen because we are human. There are still many questions to answer about human behavior, how we see that behavior, and the conclusions we make about people who we know or don’t know that well.