Let’s say you sign up online for a free yoga class. But on the day of the class, you feel sick, and you don’t want to go to the class.

Do you go?

What about this? The yoga class wasn’t free. You paid $15 to attend the class, but you still feel sick on the day of the class.

Do you still go?

Most likely, you may or may not go to the free class. But you’re not alone if you stick out the $15 yoga class because you have already paid. If you decide to go, you’ve fallen into the trap of the sunk cost fallacy.

What is the Sunk Cost Fallacy?

The sunk cost fallacy, sometimes called the “Concorde fallacy”, is the inclination to follow through on commitments or events based on prior investments, be they financial, time, or any other resource. The term "Concorde fallacy" is derived from the Concorde jet project between Britain and France. Despite its evident unprofitability as the project progressed, both nations continued to fund it because of the significant amounts already invested. Essentially, they tried to justify past expenses by investing further, even when the outcome looked bleak.

While logical fallacies are typically explored in the domain of psychology, the sunk cost fallacy enjoys extensive attention in behavioral economics. This is because it directly concerns decision-making related to costs, gains, and losses.

A succinct way to understand this is that “prior investments tend to justify further expenditures.” For instance, once we have expended money on an activity, we are more inclined to endure additional "costs," such as sacrificing an hour of sleep for a yoga session or risking health deterioration.

The essence of the “sunk cost” is that it represents a past, irretrievable loss. Take the $15 yoga class as an example; once spent, you can't reclaim your $15. Yet, driven by the fallacy, one might still attend the yoga class to avert the perception of that $15 being “wasted.” Ironically, this could lead to subsequent setbacks, whether monetary or in other forms, such as worsening health.

Examples and Studies

This payment doesn’t have to be in currency or involve attending events. Let’s say you spend $15 on a pizza. After a few slices, you’re already full. But you still feel obligated to eat the entire pizza since you spent $15 on it.

Or you go to school for communications. Two years into your degree, you realize that you don’t want to major in communications anymore. But rather than completely starting over or dropping out, you complete your degree because you have already put so much time and effort into the degree.

The cost doesn’t even have to be something that came out of your pocket. Let’s go back to the pizza example. A study asked participants to imagine that they were full after eating some cake. They were then told that the cake was bought by a local bakery or shipped in from a more expensive location. They were then told to imagine that they had bought the cake themselves or that someone had bought it for them.

Whether the person bought the cake or someone else bought the cake, the participants were likely to keep eating the expensive cake. Whether you paid for the yoga class or your friend did, you’re more likely to fall into the sunk cost fallacy.

Example 1: Committing to an Event

It can be hard to stick to new habits. But if you want to use the Sunk Cost fallacy to your advantage, sign up for a challenge, a class, or an event before you go. Reserve a spot at every Thursday evening yoga class for the next month. RSVP to the charity fundraiser three months ahead of time. Add your name to the auditions for the school play. Whatever you do, the first step is committing to be present. Once you take this step, you are much more likely to follow through.

When we commit to an event, we are less likely to cancel. After all, we’ve already committed time and effort to sign up for the event. Those costs are sunk costs - you can’t get that time and effort back, whether you show up at the event or not.

Example 2: Sticking out a Bad Movie

Let’s say you go to see a new movie at the theater. An hour into the film, you couldn’t be more bored. Everything about the movie is purely awful, and you want to get up and leave. But you’ve made it this far into the movie and feel you might as well stick it out until the end.

The sunk costs here may be time, the effort to go to the movie, the cost of the ticket and your popcorn, etc. You won’t get any of that back by watching the entire film, but somehow you feel that it’s better than just getting up and doing something else with your time.

Example 3: “I’ve Driven All This Way…”

Here’s another example. You have the day off, so you pack up the car and drive two hours to get to the beach. As soon as you leave your car, it starts to pour. It doesn’t look like it’s going to let up anytime soon!

You could turn around and go home - you won’t get those lost two hours of driving back anyway. But instead, you decide to make the best of it. You may not go to the beach, but maybe you decide to go to the nearby arcade or a nice restaurant, so the trip is “worth it.”

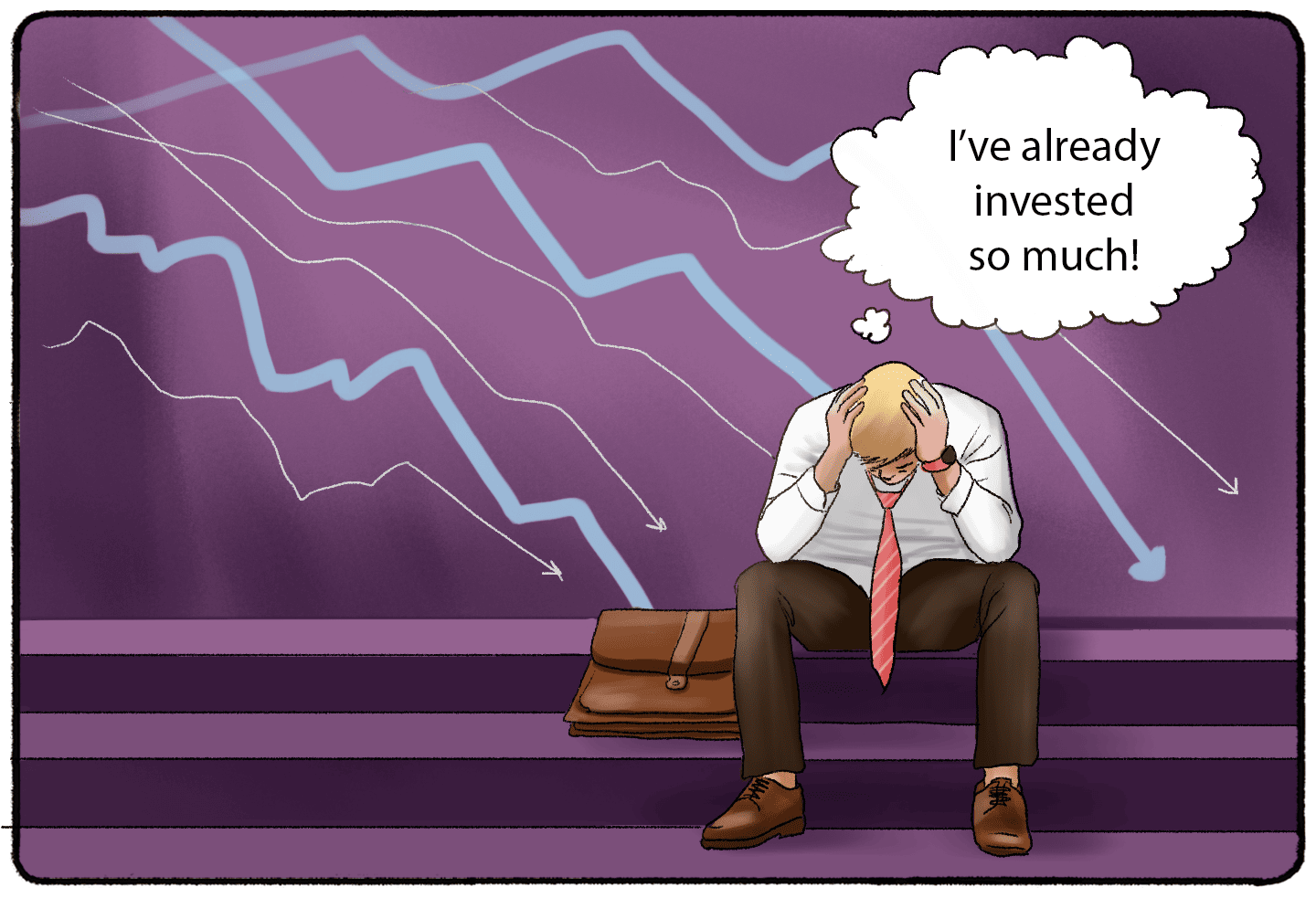

Example: 4: Holding Onto a Stock/Investment That You Paid For

There are a lot of examples of the sunk cost fallacy influencing our decisions in everyday life. However, the sunk cost fallacy also influences how we conduct business.

Think about investing in a business or a stock. You put money and support behind something, hoping that it will succeed and pay you back later. But if the stock does poorly, you may see your investment slip away from you.

The sunk cost fallacy might tell people to hold onto their stock, even if they see the stock prices falling dramatically. The person already paid for the stock, so it might seem easier to hold onto the investment and “wait things out” rather than accept the losses, sell, and invest in a new business. This example shows how dangerous and costly the sunk cost fallacy can be.

What causes it?

Why do we fall into the trap of the sunk cost fallacy? A few phenomena in psychology may explain why.

Loss Aversion

One of the ideas that support the sunk cost fallacy is loss aversion. Loss aversion is the phenomenon of wanting to avoid losses before we seek gains.

Let’s go back to that idea of the yoga class. There are a lot of things that you could gain by not going to the yoga class. You could get an extra hour of sleep or avoid waiting in traffic. You could feel better sooner and avoid seeing the doctor for medication. You could instead call up a friend and have a nice chat on the phone without having to sweat.

And yet, our minds first go to the sunk cost. You lost $15. How are you going to avoid that loss?

Sense of Responsibility

But there’s more that goes into the sunk cost fallacy. Psychologists also credit the belief that we should not be wasteful, or that we have a sense of responsibility to complete something, as reasons why we fall into the trap of the sunk cost fallacy.

This argument often comes up when we think about wasting food or following through with promises. Paying $15 for that yoga class doesn’t mean you forked over some cash. It means that you committed the teachers or the organization running the class. RSVPing doesn’t cost a thing. But paying the “price” of committing to an event makes us more likely to go, even when objectively, the gains of not going might outweigh the loss that we have already paid.

Quiz

Okay, let’s test your knowledge of the sunk cost fallacy.

Question 1:

The sunk cost fallacy explains why we are likely to go through with an event when ______.

Answer:

We have already “paid” for the event.

Question 2:

True or false: the sunk cost fallacy only applies to monetary costs.

Answer:

False! Any “cost” may lead us to fall into the sunk cost fallacy.

Last question:

The sunk cost fallacy is related to the idea that we are more likely to avoid losses than seek gains. What is that idea called?

Answer:

Loss aversion