If you're here, you are probably researching functional fixedness to help you solve a problem or write a paper. Have no fear since this page aims to give you everything you need to know, including a few functional fixedness examples!

What is Functional Fixedness?

Functional fixedness is a mental obstacle that makes us see objects exclusively functioning traditionally. We cannot get past these fixed functions of objects or tools. This stunts our creativity and may hold us back from seeing an object's full potential.

Why Do We Experience Functional Fixedness?

Functional fixedness, like other biases and heuristics, streamlines our cognitive processes, aiding us in rapidly understanding the world around us. By learning from previous knowledge and experiences, we can navigate situations more efficiently. For instance, consider the teacup you encounter every morning. Instead of pondering its potential uses each day, you intuitively recognize it as a vessel for your tea. This immediate association, a sort of "mental shortcut," ensures you don't waste precious morning minutes deliberating its function.

These mental shortcuts, termed heuristics in psychology, are invaluable. They save time and effort by enabling us to know how to interact with familiar objects instantly. However, herein lies a double-edged sword. While it's undoubtedly helpful to identify a teacup primarily for tea drinking, being trapped within this singular perspective can be limiting. Recognizing an object's primary purpose is vital, but an inability to think beyond that predefined context can pose distinct disadvantages.

Heuristics and Functional Fixedness: Cognitive Pathways in Decision-Making

In cognitive psychology, understanding how humans make decisions and solve problems is central to comprehending the complex nature of the human mind. Heuristics and functional fixedness are two concepts that illustrate the shortcuts and potential pitfalls our minds take in this process. Let's delve into these concepts and explore their relationship.

Heuristics: Mental Shortcuts to Quicker Decisions

Heuristics are mental shortcuts that our brain uses to simplify complex decision-making processes. Instead of analyzing all available data when deciding, the brain uses heuristics to quickly arrive at a solution based on patterns and previous experiences. While these shortcuts can be incredibly efficient, they can sometimes lead to errors or biases.

For instance, the availability heuristic suggests that people base the likelihood of an event on how easily they can recall similar events from memory. This might lead someone to overestimate the risk of shark attacks after seeing a news story on one, even if such events are rare statistically.

Functional Fixedness: Stuck in Established Patterns

On the other hand, functional fixedness is a cognitive bias that limits our ability to see alternative uses for objects or methods beyond their traditional or known functions. It is the tendency to be "fixed" in our understanding of how something should function, based largely on prior experiences and knowledge.

For example, viewing a newspaper strictly as a medium for reading news might prevent someone from considering its use as a tool for cleaning windows, packing material, or even craftwork.

Comparing the Two

While both heuristics and functional fixedness relate to cognitive shortcuts and biases, they manifest differently:

- Nature of the Process: Heuristics are general decision-making shortcuts that can apply to various situations and help us navigate the world more efficiently. In contrast, functional fixedness is about seeing objects or methods in a limited scope based on their familiar functions.

- Outcome: Heuristics can often lead to reasonably accurate outcomes due to their basis in frequent experiences. However, they can also result in cognitive biases and errors. Functional fixedness, meanwhile, typically leads to limited problem-solving abilities and curtails creativity.

- Advantages & Pitfalls: Heuristics help speed up decision-making in a world brimming with information. They're essential for daily function. However, their reliance on past patterns can sometimes misguide us. On the other hand, functional fixedness primarily presents as an obstacle to innovative thinking and creative problem-solving.

Interrelation in Cognitive Processes

Despite their differences, heuristics and functional fixedness can sometimes intersect. For instance, one might use a heuristic to quickly decide how to use an object based on its most familiar function, leading to functional fixedness. Conversely, functional fixedness might cause someone to default to a heuristic way of problem-solving, relying on established patterns rather than seeking innovative solutions.

While both heuristics and functional fixedness highlight the brain's propensity for simplification and efficiency, they also underscore the importance of awareness in our cognitive processes. We can foster more thoughtful, creative, and informed decision-making by recognizing when we might be relying too heavily on mental shortcuts or getting stuck in established patterns.

Examples of Functional Fixedness Holding Us Back

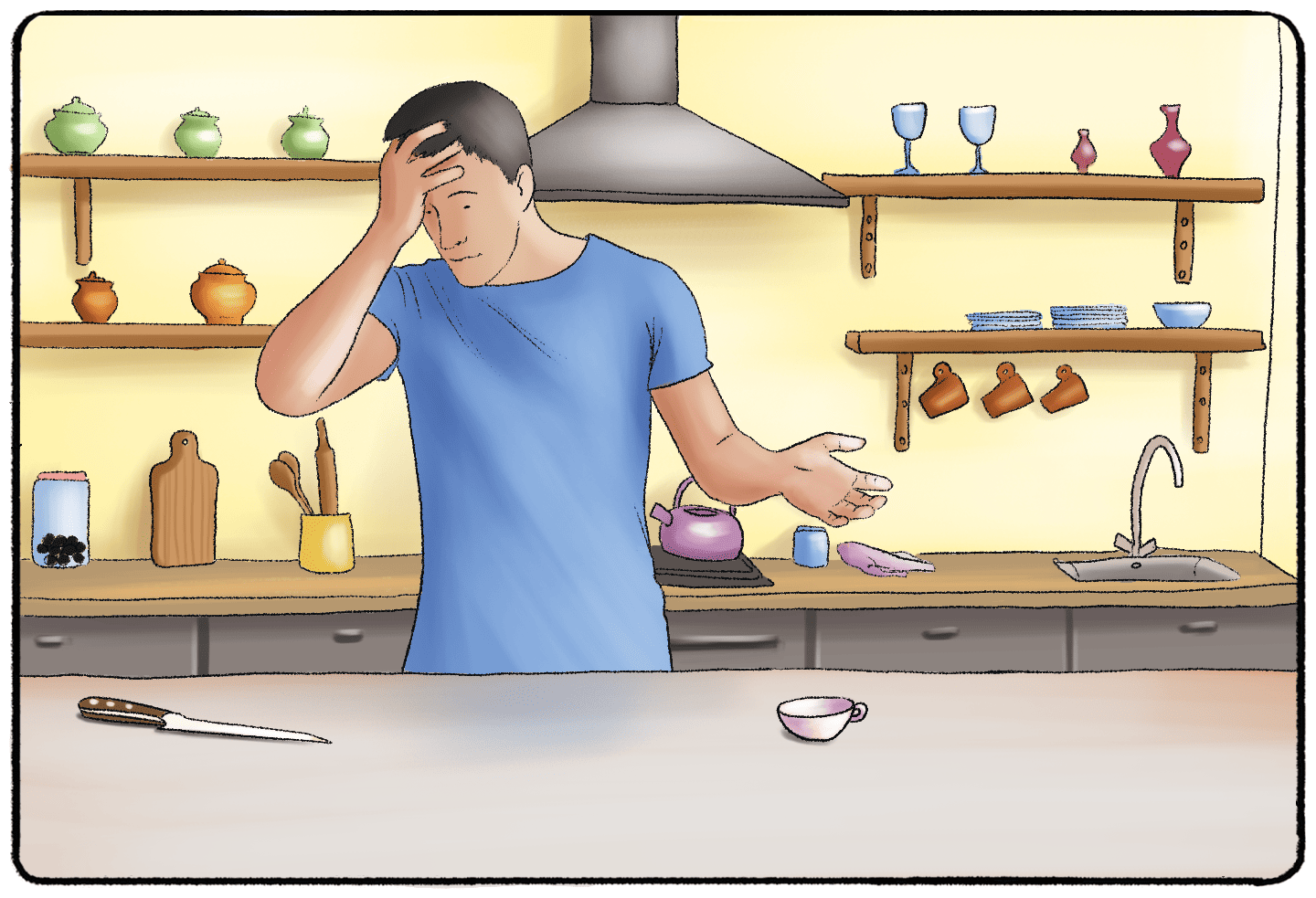

Say you have a blunt kitchen knife that you need to sharpen. However, you don’t own a knife sharpener. Would you think of using the unglazed ring around the bottom of your teacup? After all, it has the same surface as a sharpening stone. Coming up with this alternative use for a teacup would quickly solve your problem. Otherwise, you would have to look for a “real” knife sharpener while using your cup only for drinking tea.

The moment we see an object, the motor cortex in our brains activates in anticipation of using it in a standard way. That means we don’t need to hesitate about reaching for a teacup when we feel like having tea. But that also means when you're looking for a knife sharpener, you're likely to glaze over that teacup because you don't take a mental shortcut from teacups to knife sharpeners. (Well, now you might!)

Being aware of functional fixedness is important because overcoming it could be the key to solving a problem.

Schemas, Prior Knowledge, and Functional Fixedness in Psychology

In the vast landscape of cognitive psychology, understanding how humans process information and navigate their world is paramount. Schemas and prior knowledge play pivotal roles in shaping our perceptions and responses to various situations, and their influence on cognitive biases like functional fixedness cannot be understated.

Schemas: Blueprint of Our Understanding

A schema is a mental framework or structure that organizes and interprets information in our brains. It's like a blueprint for categorizing and understanding the world around us. Schemas are created from accumulated experiences, cultural background, and learned knowledge. For instance, we have schemas about what constitutes a typical "bird" or how a usual "restaurant" operates. When we encounter information or experiences that fit into our existing schemas, it reinforces them. Conversely, when we encounter anomalies, we adjust our schema (accommodation) or try to fit this new information into our existing schemas (assimilation), as posited by Jean Piaget, a renowned developmental psychologist.

The Role of Prior Knowledge

Our past experiences significantly shape our present and future actions. Prior knowledge serves as a foundation upon which we build new knowledge. When faced with a situation, our brain quickly taps into the repository of prior experiences to find a suitable response or solution. This prior knowledge is a guidepost, helping us navigate familiar situations swiftly and efficiently.

Linking to Functional Fixedness

However, the reliance on schemas and prior knowledge can sometimes limit our cognitive flexibility, leading to functional fixedness. When too deeply entrenched in our pre-existing understanding of an object's function, we can become "fixed" in our approach, hindering our ability to see alternative uses or solutions. Our brain defaults to follow the well-trodden path of past experiences and established schemas. This is where functional fixedness comes into play. For example, if our schema of a "book" is strictly an object for reading, we might overlook its potential use as a doorstop or a makeshift monitor stand.

Functional fixedness, in many ways, is a byproduct of reliance on schemas and prior knowledge. While these cognitive structures help us process information efficiently, they can sometimes act as blinders, narrowing our field of vision and restricting creative problem-solving.

In the Broader Context of Cognitive Psychology

In psychology, schemas, prior knowledge, and functional fixedness are intertwined. They are all part of the broader cognitive structures and processes that dictate how we perceive, think, and act. Recognizing their interconnectedness can help us understand why we sometimes get stuck in particular patterns of thought and how we can potentially break free to foster innovation and creativity. By challenging our established schemas and being open to new experiences, we can mitigate the effects of functional fixedness and open the doors to a more flexible and adaptive way of thinking.

Examples of Overcoming Functional Fixedness in Everyday Life

You might identify these examples as "life hacks," but they are all forms of pushing past functional fixedness and seeing uses for everyday objects in new lights.

- Want to keep your door open? Tie a rubber band around it!

- Need to prop up your phone? Use upside-down sunglasses.

- Place a pool noodle under your child's fitted sheet to prevent them from rolling out of bed.

- Worried about your gear stick getting too hot in your car? Put a koozie over it!

- Need a last-minute speaker? Cups (plastic and glass) and toilet paper rolls are great alternatives.

- Preparing to serve condiments at a party but don't want to waste dishes? Place your condiments or sauces in a cupcake tin!

- Use a shoe rack to hang cleaning supplies.

- Clothespins are a great way to hold onto nails before you start hammering!

- Did your flip-flop fall apart because the hole is too big? Use a bread clip to keep the strap in place. (Bread clips are also a great way to organize and separate cords.)

- Looking for tiny things within your carpet? Roll some pantyhose or spandex over your vacuum to attract them without sucking them into your vacuum!

- Use your seat warmer to keep food warm after you pick it up from a restaurant!

- Hair straighteners make great collar irons in a pinch.

- Don't have a juicer? Use tongs to get everything out of lemons or limes!

See how much you might have been missing out on? If all these hacks are within our grasp, what other uses could you consider for everyday items?

Who Discovered Functional Fixedness?

The term “functional fixedness” was coined in 1935 by German Gestalt therapist Karl Duncker who contributed to psychology with his extensive work on understanding cognition and problem-solving.

Duncker’s Candle Experiment

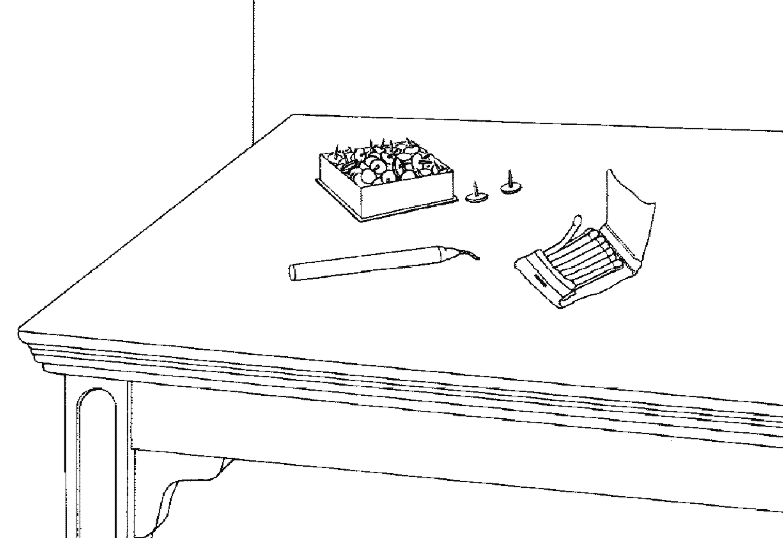

Duncker conducted a famous cognitive bias experiment that measured the influence of functional fixedness on our problem-solving abilities.

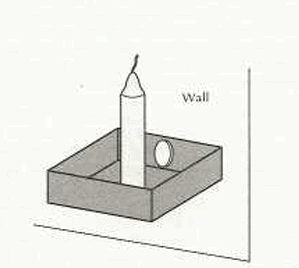

He handed the participants a box of thumbtacks, a candle, and matches. He then asked them to find a way to attach the lit candle to a wall so the wax wouldn’t drip on the floor. The solution consisted of removing the tacks from the box, tacking the box to the wall, and placing the candle upright in the box.

Pretty simple, right?

But most participants couldn’t solve this problem. They saw the box only as something that was used for holding tacks. Duncker observed a "mental block against using an object in a new way that is required to solve a problem" in these participants. To find a solution, they would first need to overcome the tendency towards the psychological obstacle holding them back—functional fixedness.

Functional Fixedness and Problem Solving

Functional fixedness is practical in everyday life and crucial in building expertise and specialization in fields where it’s important to come up with quick solutions. But as we saw in Duncker’s experiment, this cognitive constraint is the enemy of creativity. Functional fixedness stops us from seeing alternative solutions and makes problem-solving more difficult.

Functional fixedness can become a genuine problem among professionals. Research shows that functional fixedness is one of large organizations' most significant barriers to innovation. If your job is to produce innovative solutions, being able to think “outside the box” is a must.

So why do we become limited when it comes to using objects?

Children, especially those under 5, are not as biased as adults. As we know only too well, toddlers won’t hesitate to turn a wall into a blank canvas for their works of art. But because they are constantly being corrected, children become more functionally fixed over time. Eventually, they realize that paper is the only acceptable support to draw on.

As we gain more experience and knowledge, we become increasingly fixated on the predetermined use of objects and tools. And the more we practice using them in certain ways, the harder it is to see other alternatives.

Knowledge and experience replace imagination and our ability to see an object for anything other than its original purpose.

How to Overcome Functional Fixedness?

The good news is that functional fixedness is not a psychological disorder that needs therapeutic intervention. We can train our minds to overcome the mental set, a problem-solving approach based on past experiences.

There are a few methods that can help break down functional fixedness and develop creative thinking:

Practicing creative thinking

The more often you try to see novel uses for everyday objects, the easier the process will eventually become. Let’s go back to the teacup. What other usages except for drinking tea (and sharpening knives) can you think of? With a bit of imagination, the same cup can become a paperweight, candle holder, cookie-cutter, bird feeder, and even a phone sound amplifier.

Practicing helps develop our ability to think creatively. It encourages something called divergent thinking, a term defined in 1967 by the American psychologist J. P. Guilford.

Contrary to convergent thinking, which focuses on finding a single solution, divergent thinking is a creative process where a problem is solved using strategies that deviate from commonly used ones.

Changing the context

Getting a fresh perspective is often useful when considering alternate approaches to a task. In a professional setting, this can mean brainstorming in a group or involving individuals from other disciplines to share their points of view.

Considering a problem from a different angle prompts us to think creatively.

Focusing on features instead of function

Another way of breaking away from habitual ways of looking at objects is to consider what they are made of instead of concentrating on their function. List an item's different characteristics, and you might come up with its alternative uses. A teacup is made of ceramic, which can be broken down into pieces to create a mosaic.

This approach helps combat functional fixedness by focusing on the object itself while distancing ourselves from the mechanics of its intended use.

Other Biases and Heuristics That Hold Us Back

Functional fixedness is not the only "mental shortcut" holding us back. If we allow ourselves to think beyond what appears to be the "obvious answer," we may do more than we could have ever imagined!

Bandwagon Effect

It's easy to agree with what other people think. Meetings go much faster when everyone agrees right away. Plus, if one person likes the idea, it's probably not so bad, right? Well, this isn't always the case. Sometimes, the bandwagon effect encourages us to go along with what everyone else is doing. (It's easy for us to "hop on the bandwagon," as they say." Will you and your colleagues find a better solution if you debate a few more options? Are you just agreeing to something because everyone else is?

Dunning-Kruger Effect

Think you know a lot about a subject? Think again. The Dunning-Kruger Effect suggests that the less we know about a subject, the more confident we are in our abilities. Let's say you go to a rock climbing gym for the first time. You look at the wall and think, "I can get the hang of this quickly!" After a few sessions, you learn that there are different grips and ways of moving your body that you would have never thought of before! The initial false sense of confidence is a result of the Dunning-Kruger Effect.

Confirmation Bias

Once we decide, we will likely search for "evidence" confirming that we are right. If you have decided to vote for a certain political candidate, for example, you may only seek out news articles and information that confirms that they are the best candidate for the job. If you decide to leave your job, you may start focusing on the worst parts of the job. Don't let the confirmation bias prevent you from seeing all sides of an argument!

Not all biases are inherently bad, but they can hold us back. When approaching a big decision or trying to solve a problem, evaluate how biases could influence your thinking. Can you push past them? Can you try something new and unexpected?