How do you know what is happening in front of you right now? How do you get a sense of what is going on?

I gave you a hint. You sense what is going on by using your senses to send input about the world to your brain. Once your brain receives sensory input, it translates and organizes this input. This process is called perception.

In my most recent videos, I have discussed the science and theories that explain perception. But this video is all about sensation. And I want to start by talking about the five main senses.

I say five main senses because we have more than just five senses.

The Main Five (Aristotelian Senses)

It may surprise you to know that we have more than five senses. After all, how many senses did you learn about in school? Five!

For centuries, scientists believed humans have five senses that send input to the brain. The man behind this theory is not a neuroscientist but a philosopher. That’s right. The five main senses are also the Aristotelian because Aristotle is the big man behind this theory. He believed that each sense worked independently of each other.

These senses are:

- Touch

- Sight

- Smell

- Sound

- Taste

As someone who uses all or most of these senses throughout the day, it makes sense (pun not intended) that these senses help us understand the world around us. And so these five senses became the core of studying how we use sensation and perception.

But there is a lot more to the senses than what Aristotle said. Before I move on, I want you to think about this question:

- When you look directly at an object, how do you know that the object is three-dimensional?

Questions like this suggest that Aristotle was wrong when he said that all senses work independently. The blending of multiple senses is at play in this example. You may know an object is three-dimensional because you have touched or felt it. Other senses, including those outside the five main senses, may also play here.

Take wine tasting or any tasting. The smell of what you are about to taste is very important, sometimes just as important as the taste.

Keeping this work between the senses in mind, let’s discuss additional senses that influence sensory perception. Neuroscientists believe we have at least 20 different senses that help us understand the world. I’ll explain just a few of the more important ones here.

Proprioception

Close your eyes. Picture your body as it is right now. What senses are you using?

Sure, you’re using touch. You may feel your hands on your desk or your butt on the seat. But you’re not using sight. You can practice this exercise without listening to anything. And you’re not using taste. Take a moment to picture your torso, the tip of your nose, or a part of the body that’s not making contact with anything. How do you know where that is?

The answer is one of the main senses discovered after Aristotle: proprioception.

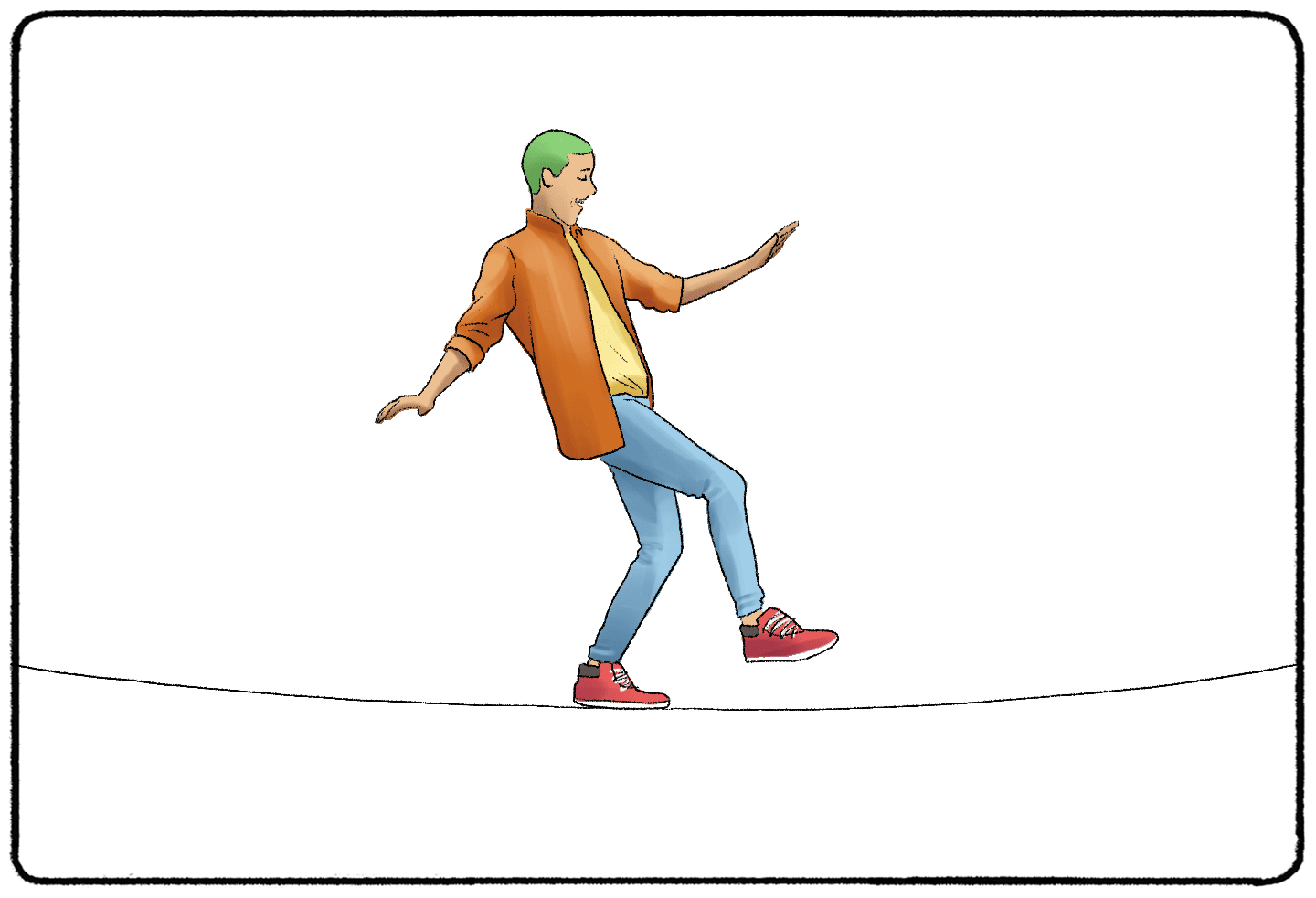

Proprioception helps us sense where our body is in space and how it’s moving. (It’s also known as “spatial awareness” or the “kinesthetic sense.”) Have you ever moved up and down the stairs without looking at them? Thank your sense of proprioception. Have you ever done a “body scan” in a meditation class? That’s all proprioception.

People with poor proprioception are likely to bump into objects or be uncoordinated. You know when children go through growth spurts or puberty and can’t understand how tall or large they are? They need to work on their proprioception.

Balance

What sense do you associate the ear with? Hearing! Within the ear are three different parts. One part is the cochlea, which contains a group of organs that help us hear. The other two parts contain organs, including the utricle and saccule. These organs help us with our sense of balance.

Our sense of balance (also known as equilibrioception) keeps us upright. It also tells us which way is up, down, left, right, etc.

The organs within the inner ear, along with the eyes and muscles throughout the body, all collect sensory input about the position and rotation of the body as it moves. If these organs do their job right, we stay upright and balanced.

Acceleration

I mentioned the utricle and saccule as two major organs within the inner ear that help us maintain our balance. These organs also help out with yet another sense - acceleration. When riding a roller coaster and feeling your body moving faster than usual, you can thank your inner ear and sense of acceleration.

Temperature

Close your eyes. How warm is it outside right now?

Yet another sense is the sense of temperature or thermoception. Thermoception is a sense that is still relatively ambiguous to neuroscientists. Sure, we all know that if we walk outside and it’s 32 degrees, we will feel colder than if we walk outside and it’s 90 degrees. But why? And why are some people more likely to feel cold while others are more likely to feel hot in the same environment? Information about thermogenic receptors and how they work with the brain is still relatively vague compared to our other senses.

Pain

Sometimes we experience pleasant touch. Other times, we experience pain. Pain, or nociception, is considered a sense all its own. Nociceptor cells are responsible for sensing threats to the body and sending that information to the brain. We have different types of nociceptor cells that cause different types of pain: the Alpha-Delta fibers produce a sharp, localized pain. The C fibers cause more burning or throbbing pain.

Both of these cells let the brain know there is a possible danger to the area of the body where the threat was detected. In response, you might feel pain. This pain is a way of letting the body know that you should pay attention to the area of the body where you are feeling pain. That is why you might feel a mosquito bite on your leg even if you are not looking there. Or if you touch a hot pan, your hand feels hot, and your body knows to remove your hand from that situation.

Pretty cool, right?

All of the senses that I just mentioned are external senses. They use input from the world outside our bodies. Other external senses include:

- Magnetoreception

- Sexual stimulation

- Pressure

- Itch

There are also internal senses that work, like nociception. These internal senses send messages to and from the about what is happening inside the body.

Hunger and Other Internal Senses

One of these senses is hunger. Hunger is an internal sense or interoception. The body senses an imbalance within the body and sends a message to the brain to correct that imbalance. In the case of hunger, the body is noticing an energy imbalance. You feel hungry because your body tells you you need more fuel.

These sensory receptors within the body may or may not be something we notice with our conscious mind. Some sensory receptors, like the peripheral chemoreceptors, make us feel dizzy or suffocated if exposed to high carbon dioxide levels. Others tell us when we are full, when we need to use the bathroom, or if we are about to vomit.

Time

And then, some senses don’t have to do with any particular body part. Take our sense of time. “Conception” is the process in which the mind experiences and perceives the passing of time. Research shows that parts of the cerebral cortex and cerebellum play a role in this sense. Conception may also explain why people get that “2:30 feeling” and tend to get tired in the early afternoon, like clockwork.

Beyond the Basics: Exploring the Lesser-Known Senses

While most of us grow up learning about the quintessential five senses – touch, sight, smell, sound, and taste – the depth and breadth of our sensory experiences go far beyond this foundational framework. Beyond the realm of the familiar, myriad lesser-known senses play an intricate dance with our nervous system, enabling us to perceive the world and our place within it in intricate ways. From the nuanced sensations of itch and pressure to the internal whispers of hunger, thirst, and balance, our bodies have a vast sensory repertoire, constantly decoding signals and ensuring our interaction with the environment is rich and meaningful.

Magnetoreception Birds, bees, and even some mammals have been observed to possess the ability of magnetoreception – or the ability to detect magnetic fields. This helps them in navigation. While the existence of this sense in humans is a matter of debate, some studies have hinted at the possibility that we might possess an innate, albeit weak, ability to sense magnetic fields.

Pressure Distinct from touch, our sense of pressure alerts us to changes in our environment that could be harmful. This is most evident when you think about diving deep underwater and feeling the weight of the water above pressing down on you. Or the change in air pressure we might feel in our ears while ascending or descending in an airplane.

Itch Though related to touch and even pain, the sensation of itching is unique. It's a sensation that compels us to scratch and arises for various reasons, from insect bites to allergic reactions. Understanding itch in a distinct sense is important because it plays a role in many skin conditions and how we treat them.

Internal Senses Beyond hunger, our body possesses a range of internal senses that help maintain homeostasis. These senses play vital roles in regulating body temperature, blood pressure, and pH levels.

Thirst Like hunger, thirst is another crucial interoceptive sense. When your body is dehydrated, specialized receptors detect the decreased volume and increased blood osmolarity, prompting feelings of thirst. This sense ensures we maintain a balance of fluids within our body.

Breathing The sensation of needing to breathe, particularly after holding one's breath, is another internal sense. It isn't driven by the need for oxygen but rather by the increasing carbon dioxide levels in the bloodstream. When these levels rise, we feel an irresistible urge to breathe.

Fullness After consuming food, stretch receptors in the stomach are activated, sending signals to the brain indicating satiety. This sense of fullness helps us regulate food intake.

Muscle Tension Inside our muscles are proprioceptors, known as muscle spindles, that detect changes in muscle length. This sense helps us determine the state of muscle contraction or relaxation, aiding in body movement and coordination.

A lot of these senses are basic concepts that you may not have understood to be senses before. Neuroscience continues expanding our ideas about senses and what constitutes a sense. This research helps us understand the brain and the bodywork and how we make sense of the world and our place in it.