Work interviews, tight deadlines, final exams, traffic jams—our everyday lives are full of potentially stressful situations. We all experience stress from time to time. And we know that stress is more than just an emotion. It can affect our whole body. When we feel stressed, our heart starts pounding faster, blood pressure rises, and our senses sharpen.

What exactly is stress, and why do we respond this way? In this article, you'll learn about the stress response, including what may make someone stressed and the physiological reactions to stress.

What is The Stress Response?

Stress is the emotional and physical tension that occurs when we feel incapable of dealing with what we perceive as a threatening situation. The stress response is the combination of physiological changes that occur when we face a stressor, like a barking dog or an oncoming car.

In emergencies, the stress response gives us the energy to react or defend ourselves. It allows us, for example, to quickly slam on the brakes to avoid a car accident.

Let’s examine in more detail how the stress response works.

What Happens During a Stress Response?

The stress response begins in the brain. When we perceive a situation as stressful, the amygdala—the area of the brain that contributes to emotional processing—sends a distress signal to the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus is a small region at the base of the brain that plays an essential role in hormone production.

When the stress response is triggered, the hypothalamus prompts the adrenal glands to release adrenaline into the bloodstream. Adrenaline causes physiological changes such as increased metabolism, blood pressure, and heart and breathing rates. All these changes prepare us to deal with stress. They improve our strength and stamina, speed up our reactions, and enhance our focus. We are now ready for what is known as the fight-or-flight response.

The fight-or-flight or acute stress response is the body's reaction to danger. It is the body’s way of keeping us safe.

After the initial stage, the adrenal glands release cortisol, which ensures the body remains alert until the danger has passed. As the cortisol level gradually falls, the stress response decreases, and the body returns to its pre-stress state.

Stress Response Stages

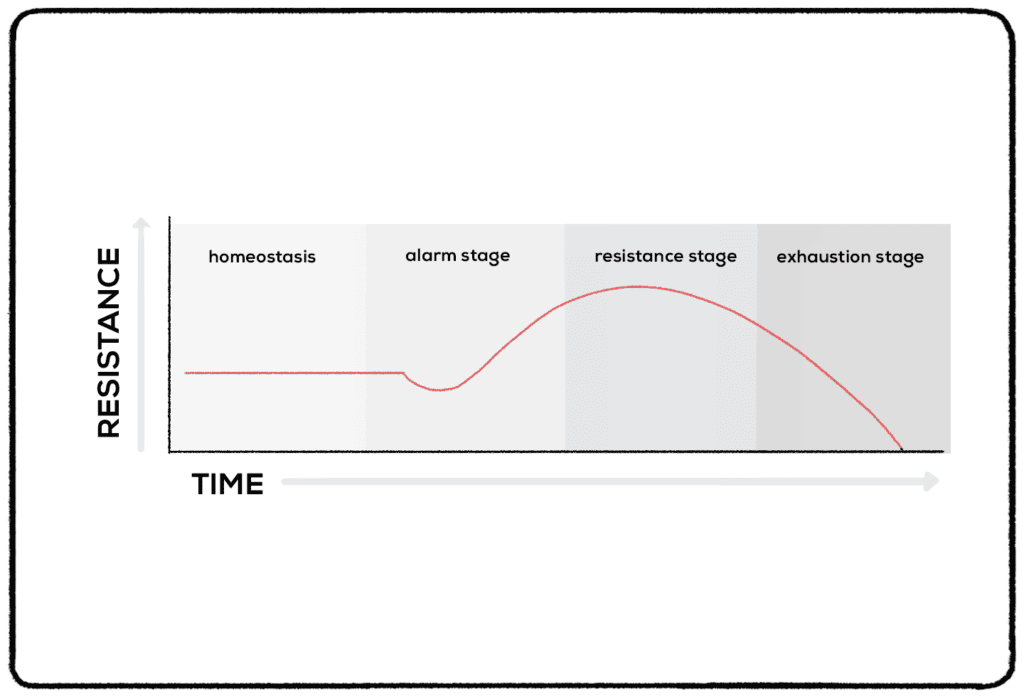

In 1946, Hungarian-Canadian endocrinologist and “the father of stress research,” Hans Selye, developed the general adaptation syndrome (GAS) theory in which he introduced stress response stages. Selye argues that when we are in a stressful situation, our body undergoes three physiological responses to stress.

Alarm Stage

The alarm stage consists of the initial symptoms that we experience under stress. The fight-or-flight response, our immediate stress reaction, occurs in this stage. When exposed to a stressor, we undergo several biological changes and are ready to take action.

Resistance Stage

At the resistance stage, our body attempts to re-establish a balance. It starts adapting to stress by decreasing activity and conserving energy. We feel calmer, and the body's physiological functions return to normal—our heart rate slows down, and blood pressure normalizes.

Although the body has started recovering, it remains on high alert. If we no longer perceive the situation as dangerous, the body will continue to repair itself until our hormone levels, heart rate, and blood pressure reach their pre-stress states.

However, certain stressful situations can last for extended periods. If we cannot resolve them quickly and our body remains on alert, we will enter the exhaustion stage.

Exhaustion Stage

Exposure to stress for long periods can drain our physical, emotional, and mental resources, leaving us with no energy to fight stress. This is when long-term psychological changes start taking place. These changes can cause symptoms such as depression, sleep deprivation, and anxiety.

The exhaustion stage is caused by prolonged or chronic stress.

What is Chronic Stress?

Suppose we remain stressed over longer periods in financial problems, sudden job loss, divorce, or exams. In that case, the stress response can become harmful. Long-term or chronic stress is when the body has difficulties returning to normal. Responses to chronic stress can be of both physical, emotional, and behavioral nature:

- Physical responses include low energy, dizziness, stomach cramps, insomnia, headache, nausea, weight loss, and sweating.

- Emotional responses manifest themselves as restlessness, agitation, depression, anger, nightmares, mood swings, anxiety, social inhibition, and forgetfulness.

- Behavioral responses to stress may appear as bad habits: smoking, excessive spending, nail-biting, fidgeting, and behaving aggressively.

Chronic stress can suppress the immune system and cause serious health problems in the long run. Consistently elevated levels of stress hormones increase the risk of heart attack and stroke and make us vulnerable to mental health problems.

Relaxation Response

The stress response depends largely on our perception of a situation. While some people are terrified of speaking in front of an audience and develop a stress response, others like being in the spotlight and remain perfectly calm before they take the podium.

The intensity of the stress response is related to the perceived threat level rather than an actual threat.

The way we respond to stress is extremely important. If we believe a stressful situation is a challenge that can be controlled, we have more chances of avoiding chronic stress and remaining healthy. Fortunately, improving the ability to deal with difficult situations and control the stress response is possible.

One of the ways of doing this is by replacing the stress response with the relaxation response.

Who Discovered the Relaxation Response?

The term relaxation response was coined in 1975 by cardiologist Dr. Herbert Benson. The relaxation response is the opposite of the fight-or-flight response. It is a way to encourage the body to release chemicals that make muscles and organs slow down. It allows us to turn off the stress response and return our body to a pre-stress state.

Benson suggests a range of tools and strategies that can be used to revert the effects of the stress response successfully. They include deep abdominal breathing, focus on soothing word repetition, visualization, prayer, tai-chi, and yoga.