I want to tell you a story about a person named John. John is passionate about gun rights. He believes everyone should have the freedom to own as many guns as they wish and that they should be allowed in all public places.

Sure, his views may seem extreme to some. But this story isn't solely about gun rights. It's about understanding the underlying psychology behind how individuals, like John or even you, might support or reinforce their beliefs. In this context, let's explore John's beliefs about guns.

Imagine John scrolling through Facebook. He spots a post from his aunt, sharing a story about a “good guy with a gun” preventing a mass shooting somewhere in the country. Without delving deeper into the video, John instantly shares the story. However, right below his aunt’s post, another headline catches his eye— it's about Australia’s success with stringent gun control measures.

What do you think is John's next move? Will he share that story too, contemplating its implications for America's safety, or scroll past, maybe even outright dismissing it?

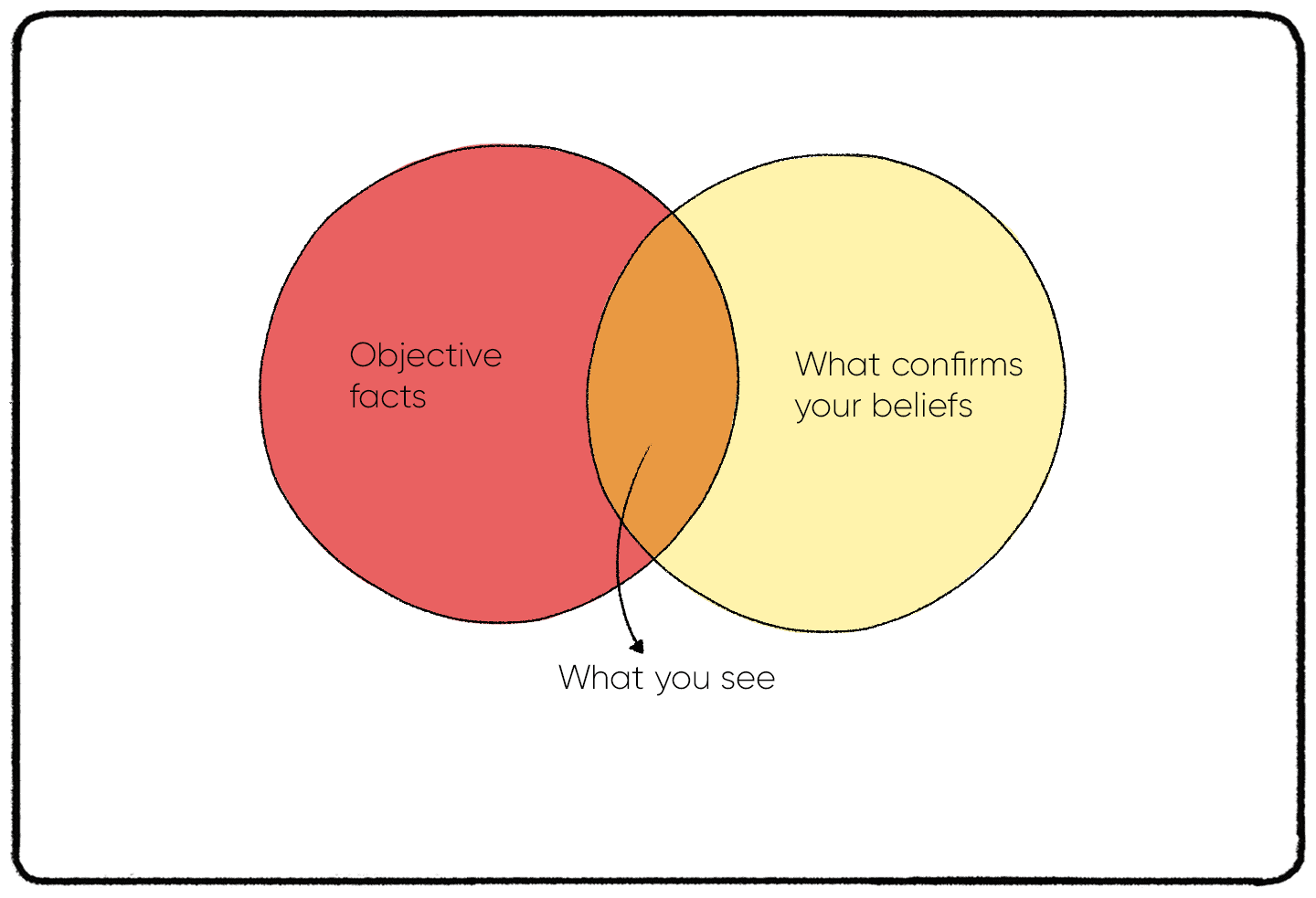

This tendency to favor information that aligns with our pre-existing beliefs, as in John's case, is a cognitive phenomenon known as confirmation bias. It's pervasive, evident daily on our social media feeds and even in the news. Perhaps you've experienced it during heated debates with colleagues, where, despite presenting concrete facts, you felt they were utterly unreceptive.

This video delves into the intricate world of confirmation bias, shedding light on how it shapes our perceptions, governs our interactions, and influences our decisions. It's an unbiased force, affecting gun enthusiasts and critics alike, supporters of Black Lives Matter and Blue Lives Matter. Essentially, it's a universal trait, and yes, it affects you too.

What is the Confirmation Bias?

Confirmation bias leads us to search for evidence that supports our current beliefs and oppose information that goes against our current beliefs. Even when facts are presented, our brain will likely dismiss the ones that challenge what we already “know” about the world.

Confirmation bias was “discovered” in 1960 by a psychologist named Peter Wason. He confirmed his theory with a simple experiment. He gave participants three numbers and asked them to figure out the “rule” for the three numbers. The example he gave was “2-4-6.”

The rule behind his set of three numbers is that they had to be chosen in ascending order. 3-6-9, 45-89-100, and 1-2,9 would have all been acceptable answers. But more than half of the students couldn’t figure out the rule.

Why?

Wason looked at the triples that the participants chose to test their theory. Some believed that the set of three numbers all had to be even, like 6-8-10 or 80-90-100. They tested sets of triplets with only even numbers to confirm their belief.

What they didn’t test were triplets which would go against their beliefs. They only sought out information that would confirm what they already believed to be true.

This shows why our fictional “John” from the beginning of the video might likely scroll past the news article that went against his view on guns.

Confirmation Bias and Fake News

Don’t believe me? Here’s another study that shows how confirmation bias can shield our ability to believe information that goes against our beliefs.

In 1979, researchers at Stanford gathered a group of participants with specific opinions on capital punishment. One group believed that capital punishment was a good thing. The other group opposed capital punishment.

The researchers made up two studies that provided statistics on capital punishment. When I say “made up,” I mean made up. The statistics were completely fake. They were designed to be equally compelling. One study supported that capital punishment benefited society and lowered crime rates. The other study supported the opposite claim.

Both studies were presented to the participants. Can you guess what happened next?

The students favoring capital punishment were likelier to say that the study confirming their beliefs was credible. The students against capital punishment were more likely to say that the same study was not to be believed and possibly “fake.” (Or dare I say, “fake news?”)

What surprised researchers even more is that participants were likelier to feel more adamant about their views after reading both studies. The participants who were initially in favor of capital punishment were more likely to feel stronger about their opinions. The participants initially against capital punishment were more likely to feel stronger about its drawbacks.

May I remind you that the studies presented to both sides were completely made up?

How it works

Confirmation bias can have harmful effects, but it also has some benefits. Let me explain.

Psychologists have been able to explain where we get confirmation bias. Our brains have a lot of information to process, especially nowadays. We don’t have time to view everything we have seen as if we’re seeing it and judging it for the first time. So we use “shortcuts” called heuristics to help us make decisions quickly.

Understanding Heuristics: The Brain's Mental Shortcuts

While confirmation bias is a cognitive phenomenon many are familiar with, it's essential to understand another critical concept that governs our decision-making process: heuristics. Often referred to as 'mental shortcuts' or 'rules of thumb,' heuristics are cognitive strategies our brains use to simplify complex problems and speed up the decision-making process. These shortcuts are not always accurate, but they're efficient.

Imagine you're trying to decide which of two restaurants to dine at. Instead of painstakingly analyzing every review for both establishments, you might rely on the most recent feedback or the overall star rating—a heuristic approach. This method may not guarantee the best meal of your life, but it significantly reduces the time and cognitive effort required to decide.

There are various heuristics that psychologists have identified, including:

- Availability Heuristic: This involves relying on immediate examples that come to one's mind when evaluating a specific topic or decision. For instance, if a friend recently had a car accident, you might overestimate the danger of driving and opt for another mode of transportation, even if, statistically, driving is reasonably safe.

- Representativeness Heuristic: Here, people judge probabilities based on resemblance. For example, if someone is shy and introverted, you might believe they're more likely to be a librarian than a salesperson, even if there are more salespeople.

- Anchoring Heuristic: This is where individuals rely heavily on the first piece of information they encounter (the "anchor") when making decisions. If you see a shirt originally priced at $100 but now on sale for $60, you might consider it a bargain, even if it is not worth $60.

Heuristics, like confirmation bias, have evolved because they're beneficial in many situations, offering a quick way to navigate our complex world. They allow us to act fast, especially when a rapid response is required. However, these mental shortcuts can also lead to systematic errors or biases in our thinking. Awareness of these can help us make more informed and rational decisions, even when our brain is looking for the quickest route.

Quick decisions have many benefits. If we see a big, furry animal in the distance, our minds will likely say, “BEAR!” and tell our feet to move in the other direction. Brains that took in every detail of every hair on the bear’s back and asked ourselves whether or not a bear was dangerous might take up a lot of time - and in that time, we might get eaten by a bear.

Other Biases Related to Confirmation Bias

So our minds help move things along with biases and shortcuts. Confirmation bias is far from the only bias that helps us make quick decisions. The Self-Serving bias tells us to give ourselves credit for good things that happen to us. The Anchoring bias gives us an “anchor” to compare information to. The Optimism Bias tells us that good things are likely to happen to us, even more so than they are likely to happen to others.

Once we have formed a belief, it’s also hard to switch gears. Holding two or more opposing beliefs is very uncomfortable for the mind. It puts us in a state of cognitive dissonance. Our brains don’t like discomfort. Brains actively try to avoid any discomfort or pain. So when they are faced with two opposing ideas, they are more likely to look to and confirm the one that they already believe in. They may reject the opposing ideas by claiming that it’s fake news or not as strong of an argument.

Cognitive biases aren’t inherently bad. They are a natural part of how the brain works and makes decisions. But, as you might have seen in the examples I showed earlier, confirmation bias can have a serious effect on the way we come to a decision about issues and limit our ability to solve problems.

Examples

Confirmation bias and outrage

Confirmation bias can put serious limits on our ability to think. But in an age where we have to process and make decisions on information faster than ever, it’s extremely important to be aware of confirmation bias and how we form opinions on political and social issues. Spreading “fake news” isn’t just a problem that affects one side of the political spectrum or the other.

Take the story about the “gender-neutral Santa” that came out a few months ago. Headlines filled up social media platforms claiming that people demanded a gender-neutral Santa. A majority or a third of people wanted Santa to be gender-neutral or even a woman.

People commented on the piece, reinforcing the idea that people were demanding too much political correctness and that things were getting out of control. This study reached the desks of the BBC and CBS.

Well, the facts behind the story don’t exactly match up with the outrage and assumptions that people gave it. No one asked or demanded anything. A graphics company behind the “study” surveyed people in an online poll asking for ways to modernize Santa. Among the ways to modernize Santa, more people suggested that Santa could use Amazon Prime, wear sneakers, or use an iPhone. The survey was not a scientific one. It fed users answers (it suggested that Santa be gender-neutral, rather than allowing participants to make that suggestion themselves) and was generally not a survey met to reflect the entire population of the US and the UK.

Less than a third suggested that Santa should be gender-neutral or a woman. No one demanded anything. There was no evidence to suggest that most people even wanted to change Santa. But people who already felt outraged by “PC culture” still took the biased study and ran with it.

This lapse of judgment and reading about the study's validity is one way we allow our confirmation bias to confirm things we already know to be true. People who think that liberals are demanding extreme measures when it comes to gender rights and breaking with tradition were likely to let the headline confirm their concerns.

Example 1: Holding Onto Stereotypes About Others

There are many hurtful stereotypes in the world about people from different countries or of different religions or races. The confirmation bias keeps those stereotypes alive.

Let’s say you hold onto the belief that law enforcement officers are evil or racist. You are more likely to seek out, pay attention to, or share stories of law enforcement officers who murdered minorities without justification. Or, maybe you hold onto a different opinion - you believe that not all cops are bad or that the people who the police have mistreated deserve what they got. You might brush off the stories that people share about cops killing unarmed minorities or believe that they are isolated incidents. You might read more into stories of people who were pulled over and interacted pleasantly with the police. Or, you might turn up the volume on stories of police doing good for the community and cutting down on crime.

This probably sounds like someone you know or on your Facebook friends list. Anytime someone clings to a stereotype, they let the confirmation bias lead them astray.

Example 2: Speculation in Courtrooms

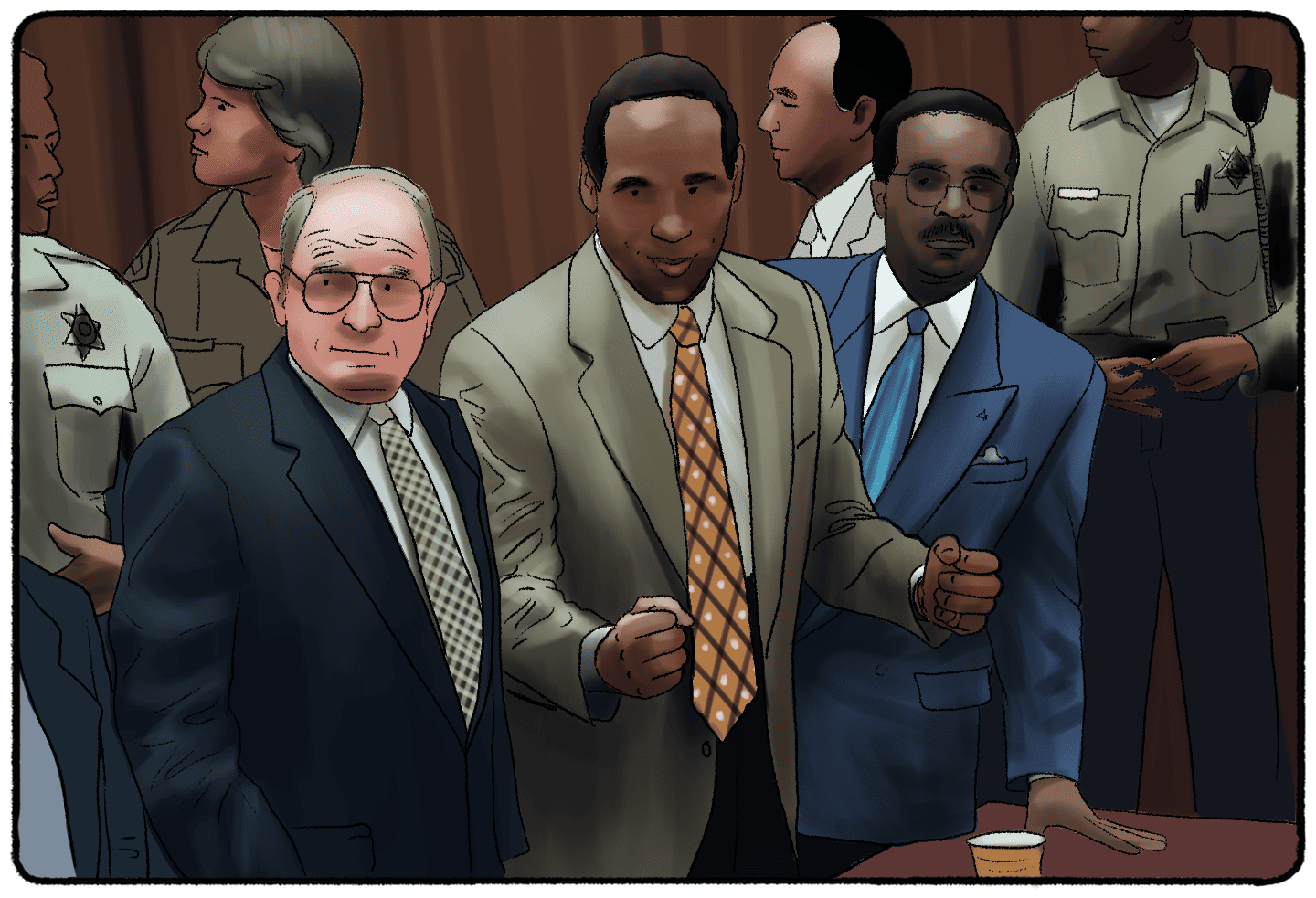

Confirmation bias can have serious effects outside of the digital world. Have you ever wondered why selecting a jury is such a long process? The judges, prosecutors, and defense attorneys are all trying to eliminate cases of confirmation bias. They want a jury that can make a fair and impartial decision about whether or not the person committed a crime.

Unfortunately, that doesn’t always happen. Look at the OJ Simpson trial. I could talk all day about the different biases that led to the “not guilty” verdict. But one is the confirmation bias. Some jurors walked into the courtroom with the belief that OJ Simpson did or did not commit the crime. They had a lot of information to take in during the trial - it lasted for months. However, the confirmation bias made the information that confirmed the jurors’ beliefs stick out most in their minds.

Example 3: Facebook Algorithms As An Echo Chamber

Have you ever heard of an echo chamber before? It’s a term used to describe spaces where people only encounter views and beliefs that mirror their own. You only hear “echoes” of the same ideas repeatedly.

Echo chambers exist online and offline. Maybe you only see news on your social media feed that confirms your beliefs. Maybe you only go to events at college with people who you know have the same political or spiritual beliefs. You might block people who get into arguments with you on Facebook. The more you isolate yourself from people who think differently than you, the farther you go into the echo chamber.

Knowledge of confirmation biases or echo chambers is not new - and it has been recognized and manipulated for years. Facebook’s algorithm encourages it. After all, it wants us to stay on the social media platform and share content. If we see more content from websites that we trust or people on our friends list who share our same beliefs, we are more likely to stay on the site and engage with the content.

Example 4: Fueling Ideas About Conspiracy Theories

Conspiracy theories like the Flat Earth Theory show how easy it is to ignore facts and hold onto your beliefs. People who believe these conspiracy theories look for any small piece of evidence that confirms what they believe. There could be dozens of explanations for the evidence they use, but conspiracy theorists don’t see it or won’t have it. They are so entrenched in their beliefs that basic science can no longer convince them.

Facebook groups and confirmation bias go hand in hand. Members of Flat Earther or other conspiracy theorists' Facebook groups share articles, photos, and videos that continue to confirm their beliefs. The more time people spend in these groups, the deeper their beliefs become. They pay attention only to the “facts” in these groups rather than seeing the larger picture.

Example 5: Confirmation Bias in The Workplace

Be on the lookout for confirmation bias at work. It can save you time and money to look at the facts before you, even if they disprove what you currently think about a project.

Let’s say you work in advertising. You believe that the target audience for your group project is moms who stay at home and don’t have a college degree. When your team brings you research on your competitors and the current market, however, the numbers show that your target audience isn’t making the purchasing decisions for their household.

Confirmation bias may stray your thinking here. Rather than going back to the drawing board and creating a message that tailors to your new target audience, you stick with your original beliefs about who is buying your product. You look for other research that supports what you believe about the market.

It’s easy to see how confirmation bias can skew your direction on a project and lead you astray.

Example 6: Warren Buffett and Confirmation Bias

If you’re one of the richest men in the world, it can be easy to fall into the confirmation bias. After all, your fortune can confirm that you’ve made great decisions in business and finance. But that’s not a trap that Warren Buffett wants to fall into. Investors can easily fall into the confirmation bias - they put all of their money into one company and ignore any signs that it might perform poorly. When an investor is led by confirmation bias, they can stick with their investments for way too long.

So Warren Buffett took specific steps to fight the confirmation bias. He invites vocal critics of his investment strategy to meetings. He sits down and talks with people who are his direct competitors. This way, he can challenge his current beliefs about his strategy and possibly look for a new, better way to invest.

Example 7: Relationship Woes

We all have that one friend who has a habit of dating the wrong people. Often, this is caused by low self-esteem. They believe that they are not good enough to date someone who is kind or wants to treat them like royalty. When someone does treat them well, they get suspicious and run away. It seems like that friend tends to seek out the worst possible partners they can find, only to confirm their beliefs that they’re not worthy of a healthy, loving relationship.

This can be frustrating for the friend’s loved ones. Maybe it’s time to talk to that friend about the confirmation bias and how it may affect who they choose to date or spend their time with.

Example 8: Failing to Listen

One of the most powerful slogans of the #MeToo movement is “Believe Women.” This slogan is necessary due to the confirmation bias. When women tell their stories of sexual harassment or misconduct, they often feel that the men in their lives are not listening to them. They are brushed off, or the men who hear the stories downplay the story's validity. This is confirmation bias at work. It’s not easy for some men to hear that their peers, an idol, or someone who looks just like them is capable of doing harmful or evil things. It’s not easy for some men to hear that they are not listening or that they are not supporting women. So they don’t listen to the evidence that supports these contradicting beliefs.

Confirmation Bias and Trustworthiness

Confirmation bias is the basis of many studies, especially as we are bombarded with more information and “fake news.” In one study, researchers examined how trustworthy people thought a news source was. It’s no surprise that people who lean to the left are more likely to consider news sources like Vox or the New York Times a trustworthy source and rate Fox News as a less trustworthy source. People who lean to the right are likelier to feel the opposite way.

In one study, researchers gave participants content from these websites. Some people saw the news source, and others were only given the text from the website to read. People who leaned to the left were more likely to rank the content from Fox News as more trustworthy when they didn’t know it was coming from Fox News. People who leaned to the right were more likely to rank the content from The New York Times as trustworthy when they didn’t know it was coming from The New York Times. Simply seeing the name of a website can easily skew our interpretation of information, no matter who you are.

The research also revealed some input about extreme opinions and bias. People who leaned far to the right or the left were likelier to have biases against news sites. This includes people who consider themselves “very liberal” or “very conservative.”

The Importance of Being Aware of Confirmation Bias

Heuristics and biases can help us make decisions quickly. We don’t have to spend an egregious amount of time processing the news and information we see on social media. And while these shortcuts can be harmless, they can seriously skew our opinions.

Be aware of how you view information and headlines as they come in. Do you read the full article? Do you read it with an open mind? How likely are you to dismiss information because it goes against what you know? How likely are you to fact-check or seek opposing information that could expand your perspective?

Keep these questions in mind and continue to challenge your biases.

Quiz

Did you learn something new about confirmation bias? Prove it! I have a quick quiz to test what you’ve learned in this video.

Question 1:

True or False: The confirmation bias leads people to reject, refute, or ignore information confirming their beliefs.

Answer:

False! It’s likely to reject, refute, or completely ignore information that opposes current beliefs.

Question 2:

_______ is a discomfort we feel when faced with opposing thoughts or beliefs.

Answer:

Cognitive dissonance! It’s one idea that supports confirmation bias.

Question 3:

What are the “shortcuts” our brain uses to make quick decisions?

Answer:

Heuristics!