In the early 1900s, a German high school teacher named Wilhelm Von Osten thought that the intelligence of animals was underrated. He decided to teach his horse, Hans, some basic arithmetics to prove his point. Clever Hans, as the horse came to be known, was learning quickly. Soon he could add, subtract, multiply, and divide and would give correct answers by tapping his hoof. It took scientists over a year to prove that the horse wasn’t doing the calculations himself. It turned out that Clever Hans was picking up subtle cues from his owner’s facial expressions and gestures.

Influencing the outcome of an experiment in this way is called "experimenter bias" or "observer-expectancy bias."

What is Experimenter Bias?

Experimenter bias occurs when a researcher either intentionally or unintentionally affects data, participants, or results in an experiment.

The phenomenon is also known as observer bias, information bias, research bias, expectancy bias, experimenter effect, observer-expectancy effect, experimenter-expectancy effect, and observer effect.

One of the leading causes of experimenter bias is the human inability to remain completely objective. Biases like confirmation bias and hindsight bias affect our judgment every day! In the case of the experimenter bias, people conducting research may lean toward their original expectations about a hypothesis without the experimenter being aware of making an error or treating participants differently. These expectations can influence how studies are structured, conducted, and interpreted. They may negatively affect the results, making them flawed or irrelevant. In a way, this is often a more specific case of confirmation bias.

Rosenthal and Fode Experiment

One of the best-known examples of experimenter bias is the experiment conducted by psychologists Robert Rosenthal and Kermit Fode in 1963.

Rosenthal and Kermit asked two groups of psychology students to assess the ability of rats to navigate a maze. While one group was told their rats were “bright”, the other was convinced they were assigned “dull” rats. The rats were randomly chosen, and no significant difference existed between them.

Interestingly, the students who were told their rats were maze-bright reported faster running times than those who did not expect their rodents to perform well. In other words, the students’ expectations directly influenced the obtained results.

Rosenthal and Fode’s experiment shows how the outcomes of a study can be modified as a consequence of the interaction between the experimenter and the subject.

However, experimenter-subject interaction is not the only source of experimenter bias. (It's not the only time bias may appear as one observes another person's actions. We are influenced by the actor-observer bias daily, whether or not we work in a psychology lab!)

Types of Experimenter Bias

Experimenter bias can occur in all study phases, from the initial background research and survey design to data analysis and the final presentation of results.

Design bias

Design bias is one of the most frequent types of experimenter biases. It happens when researchers establish a particular hypothesis and shape their entire methodology to confirm it. Rosenthal showed that 70% of experimenter biases influence outcomes in favor of the researcher‘s hypothesis.

Example of Experimenter Bias (Design Bias)

An experimenter believes separating men and women for long periods eventually makes them restless and hostile. It's a silly hypothesis, but it could be "proven" through design bias. Let's say a psychologist sets this idea as their hypothesis. They measure participants' stress levels before the experiment begins. During the experiment, the participants are separated by gender and isolated from the world. Their diets are off. Routines are shifted. Participants don't have access to their friends or family. Surely, they are going to get restless. The psychologist could argue that these results prove his point. But does it?

Not all examples of design bias are this extreme, but it shows how it can influence outcomes.

Sampling bias

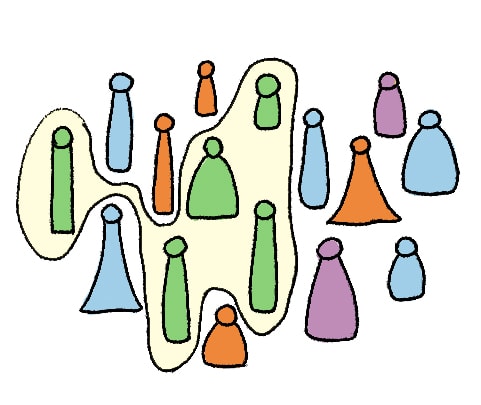

Sampling or selection bias refers to choosing participants so that certain demographics are underrepresented or overrepresented in a study. Studies affected by the sampling bias are not based on a fully representative group.

The omission bias occurs when participants of certain ethnic or age groups are omitted from the sample. In the inclusive bias, on the contrary, samples are selected for convenience, such as all participants fitting a narrow demographic range.

Example of Experimenter Bias (Sampling Bias)

Philip Zimbardo created the Stanford Prison Experiment to answer the question, "What happens when you put good people in an evil place?" The experiment is now one of the most infamous experiments in social psychology. But there is (at least) one problem with Zimbardo's attempt to answer such a vague question. He does not put all types of "good people" in an evil place. All the participants in the Stanford Prison Experiment were young men. Can 24 young men of the same age and background reflect the mindsets of all "good people?" Not really.

Procedural bias

Procedural bias arises when how the experimenter carries out a study affects the results. If participants are given only a short time to answer questions, their responses will be rushed and not correctly show their opinions or knowledge.

Example of Experimenter Bias (Procedural Bias)

Once again, the Stanford Prison Experiment offers a good example of experimenter bias. This example is merely an accusation. Years after the experiment made headlines, Zimbardo was accused of "coaching" the guards. The coaching allegedly encouraged the guards to act aggressively toward the prisoners. If this is true, then the findings regarding the guards' aggression should not reflect the premise of the experiment but the procedure. What happens when you put good people in an evil place and coach them to be evil?

Measurement bias

Measurement bias is a systematic error during the data collection phase of research. It can take place when the equipment used is faulty or when it is not being used correctly.

Example of Experimenter Bias (Measurement Bias)

Failing to calibrate scales can drastically change the results of a study! Another example of this is rounding up or down. If an experimenter is not exact with their measurements, they could skew the results. Bias does not have to be nefarious, it can just be neglectful.

Interviewer bias

Interviewers can consciously or subconsciously influence responses by providing additional information and subtle clues. As we have seen in the rat-maze experiment, the subject's response will inevitably lean towards the interviewer’s opinions.

Example of Experimenter Bias (Interview Bias)

Think about the difference between the following sets of questions:

- "How often do you bathe?" vs. "I'm sure you're very hygienic, right?"

- "On a scale from 1-10, how much pain did you experience?" vs. "Was the pain mild, moderate, or excruciating?"

- "Who influenced you to become kind?" vs. "Did your mother teach you to use manners?"

The differences between these questions are subtle. In some contexts, researchers may not consider them to be biased! If you are creating questions for an interview, be sure to consult a diverse group of researchers. Interview bias can come from our upbringing, media consumption, and other factors we cannot control!

Response bias

Response bias is a tendency to answer questions inaccurately. Participants may want to provide the answers they think are correct, for instance, or those more socially acceptable than they truly believe. Responders are often subject to the Hawthorne effect, a phenomenon where people make more efforts and perform better in a study because they know they are being observed.

Example of Experimenter Bias (Response Bias)

The Asch Line Study is a great example of this bias. Of course, researchers created this study to show the impact of response bias. In the study, participants sat among several "actors." The researcher asked the room to identify a certain line. Every actor in the room answered incorrectly. To confirm, many participants went along with the wrong answer. This is response bias, and it happens more often than you think.

Reporting bias

Reporting bias, also called selective reporting, arises when the nature of the results influences the dissemination of research findings. This type of bias is usually out of the researcher’s control. Even though studies with negative results can be just as significant as positive ones, the latter are much more likely to be reported, published, and cited by others.

Example of Experimenter Bias (Reporting Bias)

Why do we hear about the Stanford Prison Experiment more than other experiments? Reporting bias! The Stanford Prison Experiment is fascinating. The drama surrounding the results makes great headlines. Stanford is a prestigious school. There is even a movie about it! Yes, some biases went into the study. However, psychologists and content creators will continue discussing this experiment for many years.

How Can You Remove Experimenter Bias From Research?

Unfortunately, experimenter bias cannot be wholly stamped out as long as humans are involved in the experiment process. Our upbringing, education, and experience may always color how we gather and analyze data. However, experimenter bias can be controlled by sharing this phenomenon with people involved in conducting experiments first!

How Can Experimenter Bias Be Controlled?

One way to control experimenter bias is to intentionally put together a diverse team and encourage open communication about how to conduct experiments. The larger the group, the more perspectives will be shared, and biases will be revealed. Biases should be considered at every step of the process.

Strategies to Avoid Experimenter Bias

Most modern experiments are designed to reduce the possibility of bias-distorted results. In general, biases can be kept to a minimum if experimenters are properly trained and clear rules and procedures are implemented.

There are several concrete ways in which researchers can avoid experimenter bias.

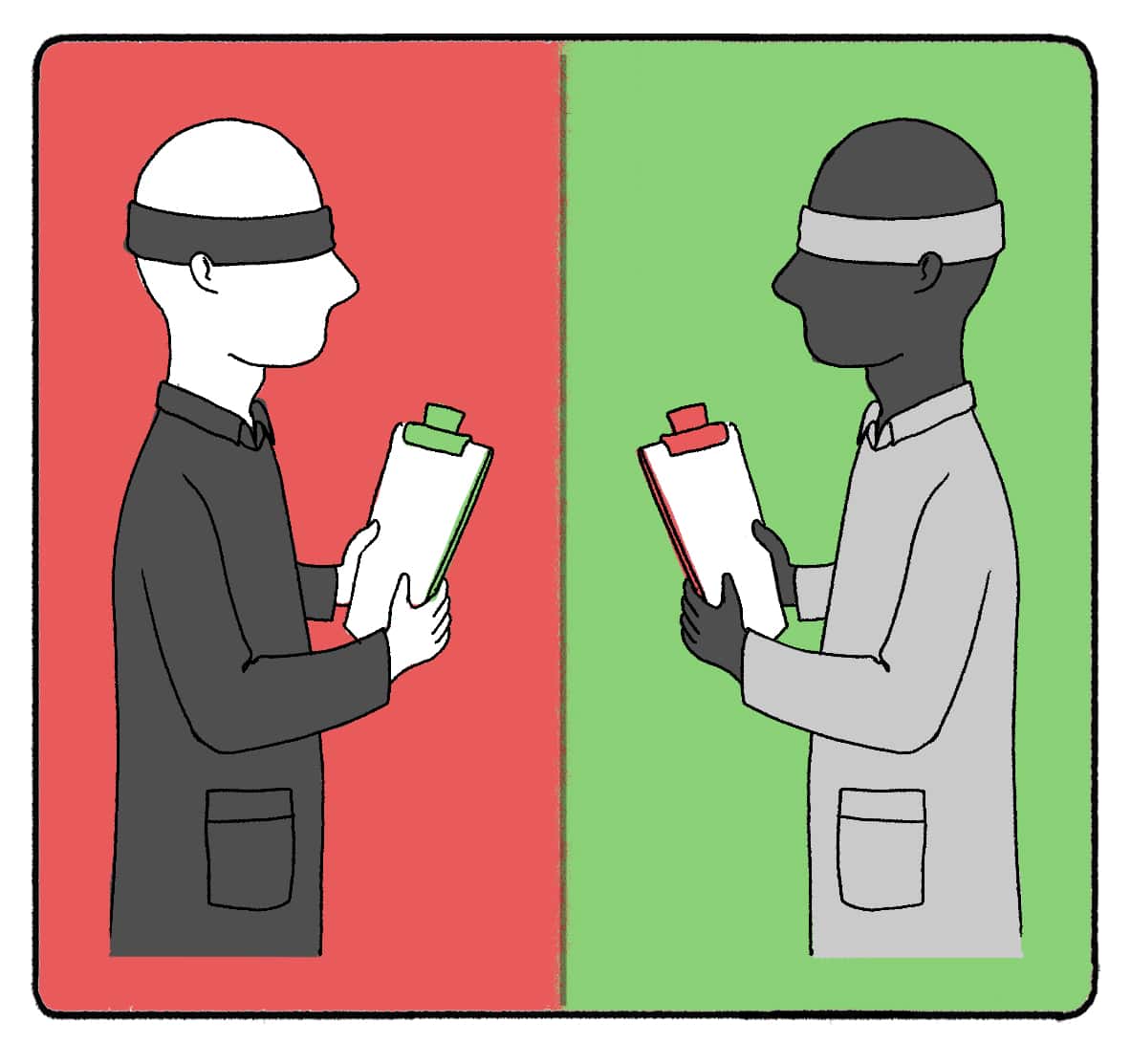

Blind analysis

A blind analysis is an optimal way of reducing experimenter bias in many research fields. All the information which may influence the outcome of the experiment is withheld. Researchers are sometimes not informed about the true results until they have completed the analysis. Similarly, when participants are unaware of the hypothesis, they cannot influence the experiment's outcome.

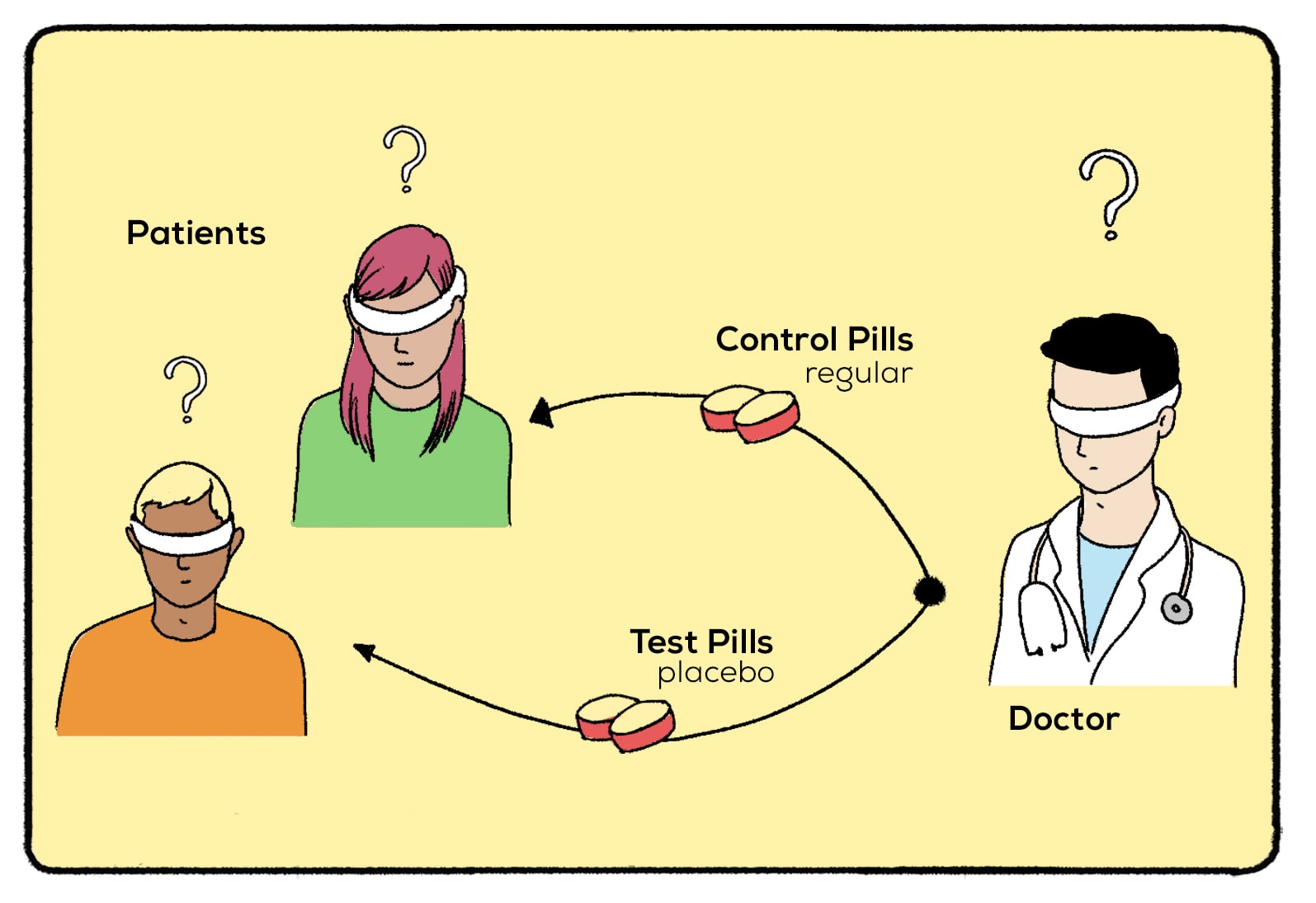

Double-blind study

Double-blind techniques are commonly used in clinical research. In contrast to an open trial, a double-blind study is done so that neither the clinician nor the patients know the nature of the treatment. They don’t know who is receiving an actual treatment and who is given a placebo, thus eliminating any design or interview biases from the experiment.

Minimizing exposure

The less exposure respondents have to experimenters, the less likely they will pick up any cues that would impact their answers. One of the common ways to minimize the interaction between participants and experimenters is to pre-record the instructions.

Peer review

Peer review involves assessing work by individuals possessing comparable expertise to the researcher. Their role is to identify potential biases and thus make sure that the study is reliable and worthy of publication.

Understanding and addressing experimenter bias is crucial in psychological research and beyond. It reminds us that human perception and interpretation can significantly shape outcomes, whether it's Clever Hans responding to his owner's cues or students' expectations influencing their rats' performances.

Researchers can strive for more accurate, reliable, and meaningful results by acknowledging and actively working to minimize these biases. This awareness enhances the integrity of scientific research. It deepens our understanding of the complex interplay between observer and subject, ultimately leading to more profound insights into the human mind and behavior.