Have you ever been convinced that you remembered something exactly as it happened, only to realize that you’d been wrong? That’s not surprising—we know that our memory is not always reliable. But what if you discovered other people had the same incorrect memory of the event?

What is the Mandela Effect?

The Mandela Effect is a phenomenon where many people think they remember an event that never occurred. The effect is named after Nelson Mandela, who supposedly died in the 1980s but never did. The term Mandela effect was coined in 2009 by paranormal researcher Fiona Broome.

Where Did The Mandela Effect Come From?

It all began at a Science Fiction and Comic book Convention she was attending in Atlanta. When one of the participants mentioned Nelson Mandela in a conversation, Broome was surprised to learn that the famous anti-apartheid activist was still alive. She was certain that Mandela had died in prison in the 1980s. She could clearly remember watching his televised funeral and listening to a speech given by his widow.

To her astonishment, Broome discovered she was not the only one to misremember this event. Many other conference attendees also remembered seeing news coverage of Mandela’s death. In reality, Mandela was released from prison after serving a sentence for almost three decades and became the president of South Africa. He died in 2013 at the age of 93.

So how can thousands of people remember details of an event completely different from what took place?

Examples of the Mandela Effect

The false memory of Mandela’s death during his political imprisonment isn't the only example of this extraordinary effect. In the past decade, hundreds of cases of the Mandela Effect have been documented in everything from current events to product brands and pop culture.

Alexander Hamilton

Most Americans have learned at some point that Alexander Hamilton was one of the United States' founding fathers. So when 2016, a team of psychologists decided to check whom Americans identify as US presidents, and they were in for a surprise. Eighty-eight percent of the participants selected Hamilton and not one of the actual former presidents like Franklin Pierce or Chester Arthur.

This false memory is probably due to a common contextual association in which Hamilton is often seen concerning early American presidents. As a result, many people have formed a false memory that Hamilton was a president himself.

Star Wars

Most of us who have watched Star Wars: Episode V–The Empire Strikes Back distinctly remember Darth Vader saying, "Luke, I am your father." Millions of people have heard what must be one of the most famous movie lines in history. Only Darth Vader never uttered these words. What he said was: "No, I am your father."

The misquotation of the iconic line has become so pervasive that it's hard to pinpoint a single origin for the incorrect version. While some have pointed to pop culture references, including episodes of shows like "The Simpsons," as perpetuating the misquote, it's essential to note that the misremembered line was already in popular discourse before such episodes aired. The ubiquity of the Star Wars franchise and frequent references across media might have contributed to the collective memory distortion. Over time, as the line was parodied, referenced, and repeated in various contexts, the inaccuracy took root, leading many to believe that Darth Vader directly addressed Luke by name.

Monopoly Man

You might have spent hours playing this classic board game without noticing that its mascot, Rich Uncle Pennybags, doesn’t wear a monocle. Many people’s memory of Mr. Monopoly with a monocle is so vivid that it’s almost impossible to believe it could be false. The Monopoly man never had any corrective lens since he first appeared in the Monopoly box in 1936. How could have so many people been wrong?

One possible explanation is that we have subconsciously combined the character of Mr. Peanut, the Planters snack mascot who sports a monocle and top hat, with that of the Monopoly man. The monocle has been mentally transferred from one character to the other as a missing element that would perfectly fit the wealthy person stereotype of Rich Uncle Pennybags.

Psychological Constructs and the Mandela Effect

The Mandela Effect is not just a fascinating oddity of collective memory. It provides a gateway into understanding the intricate interplay of cognitive and social-psychological mechanisms that shape our beliefs and perceptions. Let's delve into the key psychological constructs intertwined with this phenomenon:

- Memory Reconstruction & Confabulation:

- Every time we recall an event, our brain reconstructs it, not merely replaying a stored video. This dynamic process opens the door to potential inaccuracies.

- Implication for Mandela Effect: Misinformation encountered after an event can introduce errors in our recollections. When similar misinformation is widely spread, it can foster collective false memories, giving rise to phenomena like the Mandela Effect.

- Schema Theory:

- Schemas act as cognitive blueprints, helping us categorize and interpret information based on prior knowledge. They greatly influence our perceptions and memories.

- Implication for Mandela Effect: If an erroneous piece of information aligns closely with an existing schema (for instance, thinking of the Monopoly Man with a monocle as fitting the "wealthy" stereotype), we might remember it in this skewed manner.

- Social Conformity & Groupthink:

- Human beings naturally tend to match their beliefs and behaviors to those of the majority, even if they might be incorrect.

- Implication for Mandela Effect: Collective memories can become reinforced within a community when individuals start aligning their memories with the perceived majority's recollection, cementing the Mandela Effect's presence.

- Misinformation Effect:

- Our memories are not immune to external influences. Post-event information can significantly sway our original recollections.

- Implication for Mandela Effect: The media, pop culture references, or even authoritative figures can spread misinformation. Over time, this can warp original memories, fostering collective misremembrances.

- Confirmation Bias:

- Once individuals form a belief or perception, they naturally seek information confirming it and tend to ignore or downplay contradictory evidence.

- Implication for Mandela Effect: This bias can intensify the Mandela Effect, especially in today's digital age. Online communities may unknowingly perpetuate false memories by predominantly sharing supporting anecdotes while neglecting contradictory ones.

- Suggestibility:

- Humans are impressionable. When an idea or memory is suggested, especially by a trusted source, they can adopt it as their own—even if it's incorrect.

- Implication for Mandela Effect: In environments like online forums, where similar experiences and memories are discussed, heightened suggestibility can lead to the rapid proliferation of the Mandela Effect.

The Mandela Effect underscores the intricacies of human cognition and the sociocultural forces at play. By examining it through the lens of these psychological constructs, we gain deeper insights into the broader patterns of how societies and communities form, share, and sometimes misconstrue collective beliefs.

More Examples of The Mandela Effect

When u/Different-Hunt-9777 asked Reddit, "What is the Mandela Effect that you have personally felt yourself?" hundreds of people commented! Some of the examples people gave included:

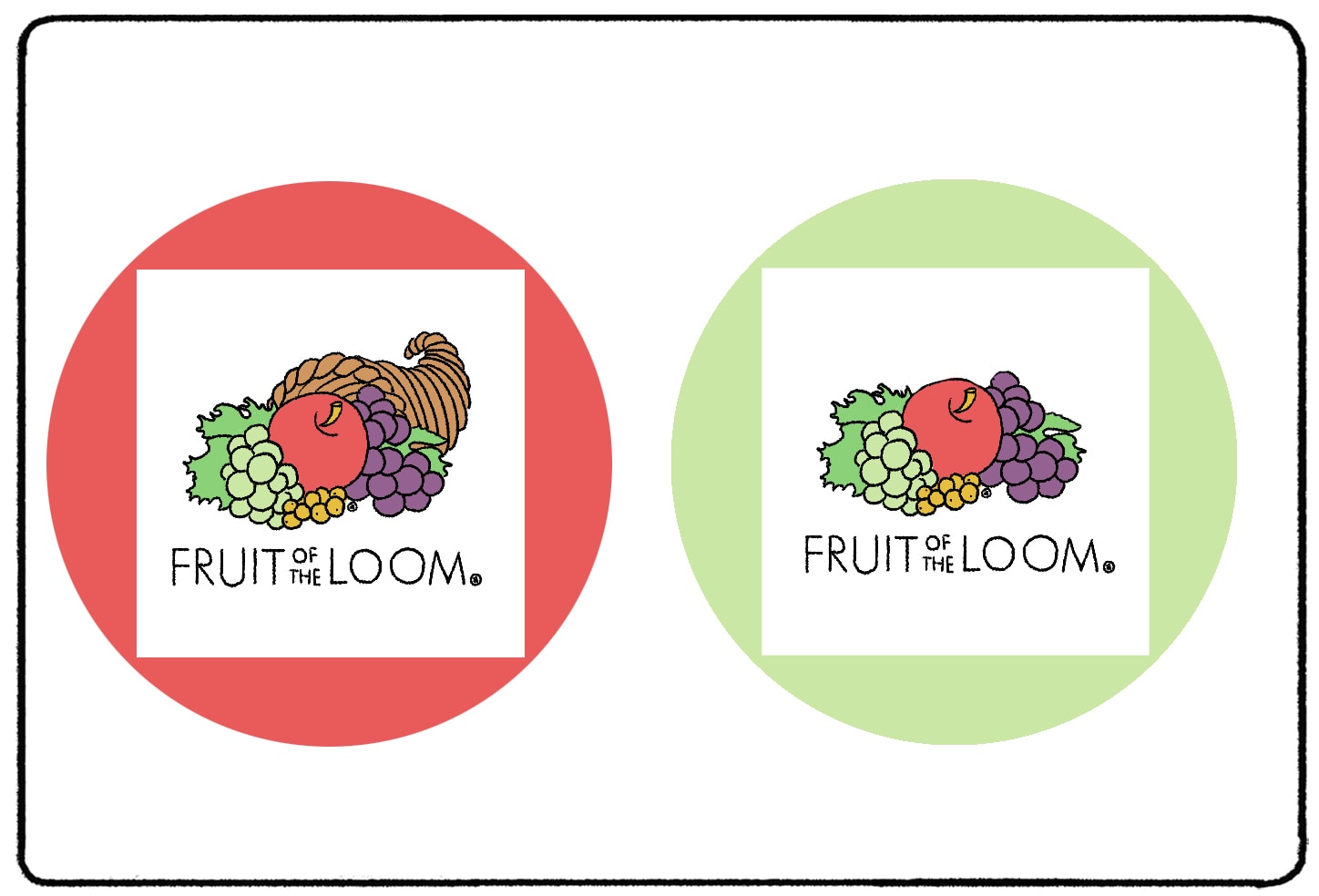

- The Fruit of the Loom logo

- "Chic-fil-a"

- Tom Cruise's shirt color in Risky Business

- Movie quotes

- Sinbad's Shazaam

Do Alternate Realities Exist?

Broome explains the phenomenon through the multiverse theory. She believes that all the different memories of the past are correct since the events are experienced in parallel universes. A false collective memory is created when several realities, each with its version of the event, become intertwined.

Quantum physicists have indeed developed a theory about the potential existence of multiple universes based on mathematical models. However, psychologists and neuroscientists propose quite a different explanation for The Mandela Effect.

How False Memories Work

The Mandela Effect can be explained through the concept of false memory initially studied by the pioneers of psychology, Pierre Janet and Sigmund Freud.

False memory is when a person recalls something that didn’t happen or remembers it differently from how it happened.

Memory is vulnerable information that changes over time. Converting short-term memory into a long-term one is called memory consolidation. But just because memory becomes long-term doesn’t mean it can never be altered again.

Every time we assess a memory, it needs to be reconsolidated. Memory reconsolidation helps reinforce the information and, at the same time, slightly changes what we remember. When recalling a memory, other more recent memories are triggered, causing several memories to get combined into one.

With the introduction of new elements, memory necessarily loses its accuracy. So although we may think that we strengthen old memories by recalling them, the opposite is true.

False memories can also be a result of a phenomenon known as confabulation. Confabulation occurs when the brain fills in gaps with fabricated, misinterpreted, or distorted information to make more sense of our memories.

If you'd like to learn more about false memories and their intricacies, I have a full article on False Memories and Memory Errors.

Mandela Effect and Suggestibility

There’s no doubt that the fast spreading of information on the internet plays a role in influencing our collective memories. Post-event misinformation is one factor that creates memory distortion and alters how we remember things.

As more and more people provide incorrect details, social misinformation becomes incorporated into our memories as facts. As a consequence, it strengthens our conviction that we remember things correctly.

Suggestibility, the tendency to believe what others suggest to be true, is pivotal in shaping our memories. It's one of the foundational mechanisms behind several false memory phenomena, including The Mandela Effect. When people around us, especially those we trust or view as authoritative, recount an event in a particular way, our brains may adopt that version, even if it's different from our original memory. Recalling a memory isn't a simple replay; each recollection can alter the memory itself. As we remember something repeatedly, especially in the light of external suggestions, our confidence in that memory can increase, even if its accuracy diminishes. This intertwining of memory and suggestibility underscores the complexity of human cognition and serves as a cautionary tale about the trustworthiness of our recollections.