Memory can be tricky. Any cognitive psychologist knows that false memories and small (or big) errors in memory happen all the time.

There are some moments that we remember so vividly. We trust our memories. We know what we saw and what we said and what we heard.

But have you ever gotten into an argument with someone over each other’s memories?

“You said it!”

“No I didn’t!”

“Yes, you did!”

“I would never say that!”

Have you ever gotten into an argument with someone, only to find out that they were right? Even though you could swear up and down that you did or did not say something, you’re proven wrong.

These moments can be very uncomfortable. Even though we trust our memories and try to be honest, our brain can play games with us. Our brain can create false memories or memory errors. But don’t worry - it’s not just you.

Everyone experiences these false memories every now and again. These errors do not always mean that your brain is failing, but if you are aware of these concepts, you are more likely to get to the truth and look at situations more objectively.

If you want to see how your memory compares to other's memories, we created a short term memory test that you can take in less than 5 minutes to see where you land.

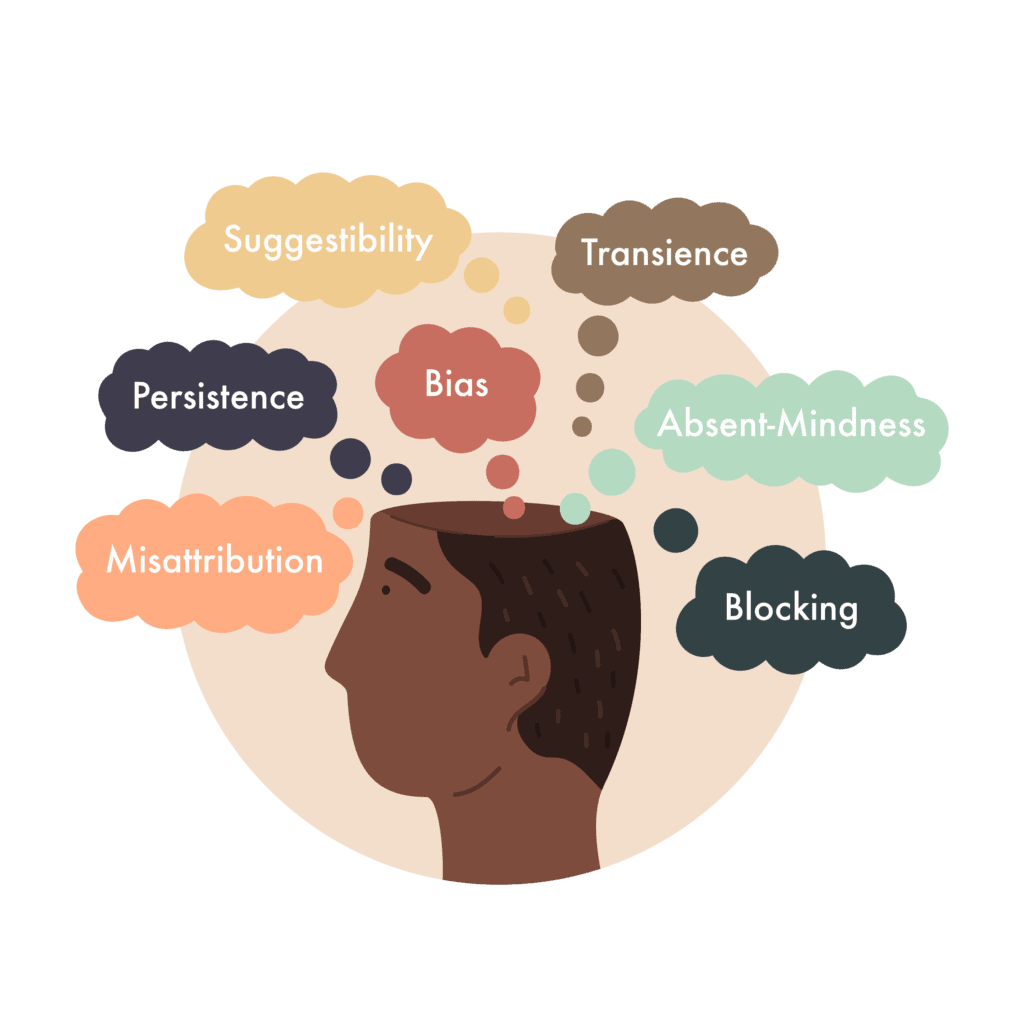

The Seven Sins of Memory

Seven concepts that lead to memory errors are the center of “The Seven Sins of Memory: How the Mind Forgets and Remembers.” In the book, Harvard professor and psychologist David Schacter dives into each concept and how it creates memory errors. In this video, we’ll just go over the brief definition of each “sin.”

Most of us do not commit these sins with ill intention. They are often honest mistakes that we can’t control - they may even be frustrating. The first three sins of memory are “sins of omission.” Sure, the memory might be there, but it is unavailable when you need to recall it. The three sins of omission in false memory are absent-mindedness, transience, and blocking.

Absent-Mindedness

Not all sins of memory come with the potential for such heavy consequences. Have you ever went into a room, only to forget why you walked in there in the first place? This is simply a case of absent-mindedness.

Absent-mindedness is caused by three things:

- Not paying attention to a task at hand (putting your glasses somewhere, only to realize you’ve misplaced them later)

- Paying too much attention to a task and failing to notice anything else around you

- Getting distracted by other thoughts or events happening around you

Blocking

Have you ever had a word or a phrase on the tip of your tongue? Your memories are “blocking” your ability to recall information. Blocking can be extremely frustrating, but usually it’s only temporary.

Transience

What did you eat for lunch yesterday? What did you eat for lunch a week ago? A month ago? Last year?

It’s no secret that memories fade over time. Even though some memories persist due to their traumatic nature or significance, other memories don’t stick. Transience simply explains the concept that memories are less accessible as time goes on. While this seems like just a fact of life, it can make a difference in eyewitness credibility.

The last four sins are “sins of commission.” They involve a memory that exists, but may be false, skewed, or contain inaccurate details. These four sins of commission are misattribution, suggestibility, bias, and persistence.

Misattribution

Misattribution, also known as source misattribution, occurs when you cannot remember the source of a memory. Say you saw a study or a fact quoted in the New York Times. In reality, you heard it quoted on a television show. It may have been a joke or fake fact on the show, but you think the credibility is that worthy of a reputable newspaper. This is an honest mistake, but an example of misattribution nonetheless.

Suggestibility

Memory errors can also be created by suggesting something about the person’s memory. Later in this video, I will talk further on how suggestibility and leading questions can make a big impact on an eyewitness’s testimony in court. But suggestibility may pop up even without ill intentions.

One example of suggestibility involves using presuppositions to suggest facts. You could ask someone who is rather suggestable, “What time in the afternoon did you see that man walking down the street?” The question can be highly suggestive.

It suggests that the person did see the man walking down the street.

It suggests that the person saw a man.

And it suggests that the time in which they saw the man was sometime in the afternoon (as opposed to the morning or the evening.) If none of those facts were established earlier, that simple question could be a case of leading a witness.

Bias

Humans are meaning-making creatures. When we observe things around us, we try to make meaning of them based on our prior knowledge. Unfortunately, that prior knowledge may be skewed by bias. And when we go back to recall our observations, that bias may taint what we remember about an incident.

Let’s go back to the man walking down the street. Based on the area that you were in at the time, the clothes the man was wearing, or even the color of his skin, your memory of that man might be biased. You might remember him to “look suspicious,” even when he was just walking down the street.

Persistence

There are some memories that we would rather forget. I’m not just talking about embarrassing moments. Anyone who has experienced trauma understands that the memories of that event, no matter how horrifying, may never go away. The opposite might happen. The memories may flood back on a moment’s notice without warning. It could be “triggered” by sensory input, like when Bradley Cooper’s character is triggered by hearing “"My Cherie Amour" by Stevie Wonder.

This is persistence. Memories continue to come back, even when people make an effort to get rid of them. Traumatic memories can cause psychological damage - when they persist, a person may display symptoms of PTSD or depression.

How Memory Errors Affect Legal Cases and Eyewitness Testimonies

The seven sins of memory don’t just inconvenience your day or make you feel embarrassed in an argument. When they are manipulated in criminal cases, they could sway the verdict one way or another.

You have probably seen examples of this in movies and television. In Making a Murderer, viewers watched footage of investigators coercing Brendan Dassey into confessing to crimes. They used tactics to suggest that Dassey was involved in the crimes. These tactics eventually led to Dassey’s confession and incarceration in 2005.

Upon reviewing the evidence over 10 years later, a federal judge stated that investigators “exploited the absence of such an adult by repeatedly suggesting that they were looking out for his interests.” Dassey’s conviction was overturned and he was released from prison.

Making a Murderer is just one example of how investigators may take advantage of the seven sins of memory (in this case, suggestibility) to create false memories or assumptions.

Loftus and Palmer (1974) and the Misinformation Effect

American psychologists Elizabeth Loftus and John Palmer created a study in order to test these theories about suggestibility. They showed a video of a car crash to multiple students. The students answered multiple questions about what they saw in the video. Loftus and Palmer’s questions were very intentional. They included one of the following questions:

“About how fast were the cars going when they _____ each other?”

They filled in the blanks with one of the following words:

- Smashed

- Collided

- Bumped

- Hit

- Contacted

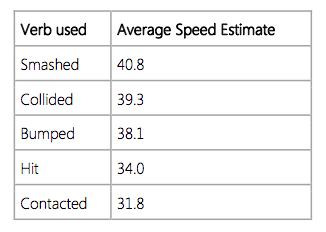

Two cars “contacting” each other does not sound as dramatic as two cars “smashing” each other, right? The psychologists thought so, too. And the results of the study show that the choice of verb made a difference in the participant’s memory of what they saw.

The people who were asked how fast the cars smashed each other predicted that they were going up to 40.8mph. When the cars contacted each other, participants reported that they were going 31.8mph.

Depending on the speed limit and other factors in a criminal case, eight miles per hour could potentially make or break a case. Suggestibility can have a powerful impact on a trial. If you are a witness or a member of a jury, these concepts and seven sins of memory are extremely important to know.

This study has become one of the most significant contributions to The Misinformation Effect.

The Misinformation Effect, coined by Loftus, is the phenomenon that describes how memories can change and become false due to exposure from misleading questions, information, or new memories.

How False Memories Form: The Skeleton Theory

Elizabeth Loftus is one of the most famous psychologists who studies false memories. She developed the “Skeleton Theory,” which explains the process in which we both acquire and recall memories. There are multiple parts to each process, and these parts can easily show how we can color memories with false information, bias, or misattribution.

Let’s break down this process.

It starts with the acquisition, or creation, of the memory. The first part of acquiring a memory is focusing on a memory to eventually store away. We are inundated with so much stimuli around us - we need to focus and select the stimuli that goes into our memories eventually.

Once that stimuli is selected, we create statements to explain what we are observing. That statement could be as simple as “there is a coffee cup on the table.” This is where semantic memory becomes important.

The last stage of this process is probably not something we can be fully aware that we are doing. It involves making meaning of our statements from past information or perceptions. This last step of the process could turn our initial observation into a statement that sounds like this: “Joe’s coffee cup is on the table.” “There is a delicious cup of coffee on the table.” “The coffee cup on the table is out of place.” etc.

There is a high potential for a person’s initial observations to make a big leap as they add statements and meaning to their memories. But this all happens before any time has passed and the person needs to recall that observation.

The second part of the skeleton theory explains what happens when a person has to recall the memory. The person recalls the memory based on the stimuli that they focused on. (They may have seen a coffee cup on the table, but not noticed the croissant next to the cup or someone telling them, “Don’t touch that coffee!”) With this observation they bring all of the memories and perceptions that have collected before and after.

The second part of recalling the memory is communicating the memory to others. They “paint a picture” of the scene with the sensory input they collected and the meaning they made from all of that input.

The result is a memory that is either accurate...or not so accurate. The skeleton theory shows how easy it is for false information or bias to slip into our memories as we both acquire them and recall them to others.

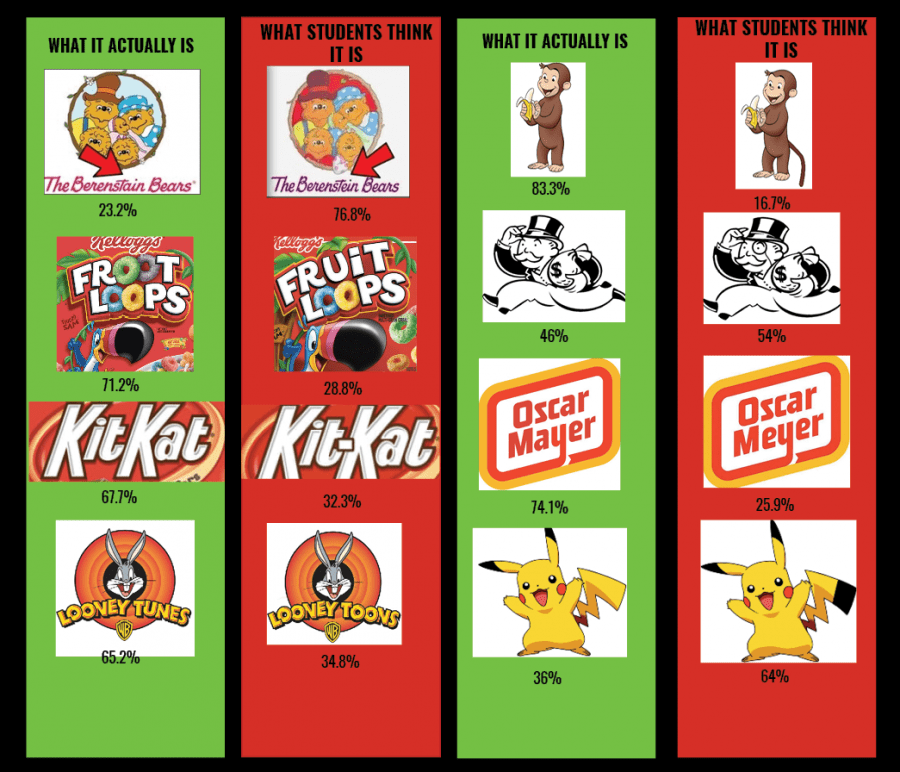

The Mandela Effect

Hannibal Lecter never said, “Hello, Clarice” in Silence of the Lambs.

Darth Vader never said, “Luke, I am your father.”

The Evil Queen in the Snow White movie never said, “Mirror, Mirror on the wall.”

The mascot of the Monopoly board games does not wear a monocle.

Curious George doesn’t have a tail.

“Jiffy” peanut butter never existed. Only “Jif.”

If you’re scratching your head or doubting me, you’re not alone. These facts have been disputed for years, and they all contribute to an eerie idea called “The Mandela Effect.”

The Mandela Effect was named after Nelson Mandela, a civil rights leader and the former President of South Africa. He passed away in 2013, but there are thousands of people who falsely remember his death in the 80s or 90s. This memory is as vivid as your memory of Hannibal Lecter’s “Hello, Clarice,” or an incorrect image of the Monopoly man.

Many people believe that The Mandela Effect explains the possibility of alternate universes. Others push the Mandela Effect into the category of “conspiracy theory.” Most people who hear about it think it’s too freaky to think about.

But given what we know about memory, and our unconscious ability to alter and acquire memories that aren’t always true, it makes sense that everyone collectively has come to believe that the real line from Star Wars is “Luke, I am your father.”

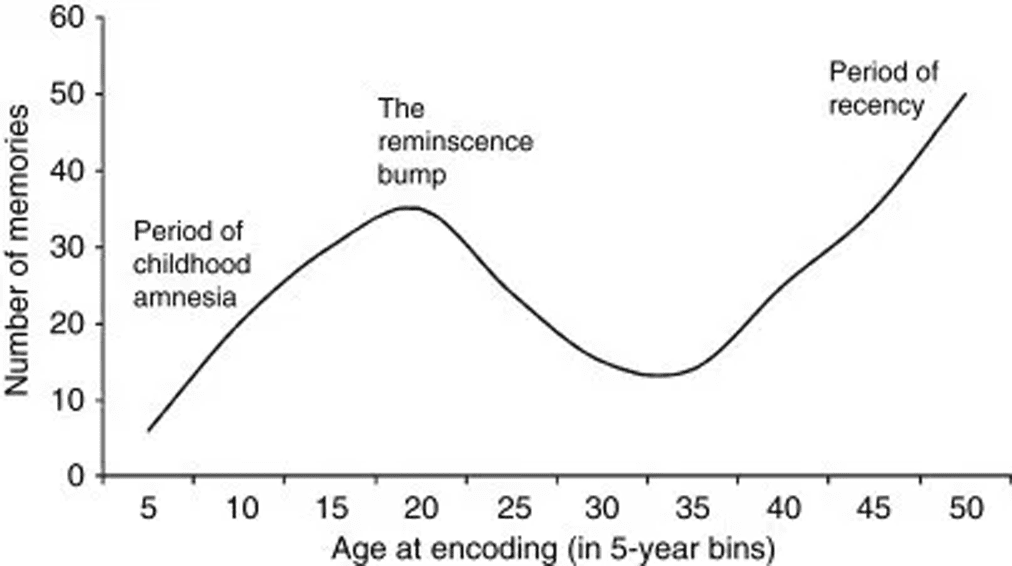

Exceptions to the Rules: The Reminiscence Bump

Think back to the information I just shared on transience. In general, this theory states that the older a memory is, the more fuzzy it is. But there are always exceptions to the rule.

Exceptional days and emotional moments stick out years after they happened. Even insignificant memories outlive other memories. One theory suggests that, even as people reach their 60s and 70s, the memories from their teens and 20s continue to be more accessible than earlier or later memories.

What is the Reminiscence Bump? A theory that suggests that people believe that they vividly remember their teens and 20s because it’s the time when people started to form their identity.

In the story of a person’s life, their teens and early 20s set up the plot and provide a context for the next few decades.

Studies on the Reminiscence Bump didn’t appear until the 1990s, so it’s hard to say whether this idea only applies to a single generation or whether it will carry on for decades to come. What this does tell us is that while transience does have an effect on what we remember, our ability to hold onto memories doesn’t move in a linear pattern.

What is Cryptomnesia?

Cryptomnesia is a phenomenon that occurs when someone has a thought that they believe is original, but is actually a memory.

One of the most overwhelming and fascinating elements of the study of memory is how much there is to consume. At any moment, we could be influenced by memories and information that stretches back ten, twenty, or thirty years. We may not be aware that misleading questions or more recent memories are influencing our thought processes.

In some cases, we may not even be aware that we are recalling a memory in the first place. This is usually harmless - until you use that “original idea” to write a speech or music. Here’s looking at you, Melania Trump and Vanilla Ice.

In 1989, psychologists Alan Brown and Dana Murphy created a term for this phenomenon: cryptomnesia.

One famous case of cryptomnesia comes from the 1970s.

In 1970, George Harrison released a song called “My Sweet Lord.” The song was a hit - but within a few years, music lovers noticed that it sounded eerily similar to “He’s So Fine,” a song written for The Chiffons. Harrison claimed that he did not realize he had heard the song before.

The issue went to court. In 1976, the court stated that Harrison “subconsciously plagiarized” the song. He did face repercussions, but none so severe as the repercussions for intentionally plagiarizing a song.

What’s Real?

Unoriginal thoughts. False memories. Leading questions.

That’s a lot to unpack in one video! But don’t worry. While the phenomena mentioned relating to false memory may make you uneasy, you are many steps closer to recognizing when you may be trapped in memory errors.

With these tools in your toolbelt, you can make more sense of your memory storage and have an easier time uncovering the truth.