Every day, you encounter rules, expectations, and the subtle pressures of society, all of which shape our behavior in ways you might not even realize. When someone doesn't follow the rules, we call it deviant behavior.

Merton's Strain Theory of Deviance is a sociological framework that explains how societal pressures can lead individuals to engage in nonconforming behavior.

This theory illustrates the disconnect that can occur between cultural goals and the means available to achieve them, which often results in a "strain" that propels people toward deviance.

Introduction to Deviance Theories

When you walk into a classroom or a workplace, you know there are rules you should follow. These rules are part of what makes a society function. But sometimes, people break these rules or norms, and this is what sociologists call deviance.

It's not just about breaking the law; it can be as simple as dressing differently or not following social cues. It's these moments that sociologists try to understand, and they have created many theories to help explain why they happen.

These range from biological theories, which look at people's genetics and physical makeup, to psychological theories that focus on individual minds. But among these stands out a sociological approach that considers the broader social structure: Merton's Strain Theory of Deviance.

It gives us insight into the social forces that can push people toward actions that the rest of society might not understand or accept.

Robert K. Merton: The Father of Strain Theory

Robert K. Merton, a significant figure in sociology, introduced the Strain Theory of Deviance in the 1930s. He was not content with simple answers; he looked deeper into the structure of society to find clues.

Born in 1910 as Meyer R. Schkolnick to a Russian family, Merton grew up in a poor neighborhood in Philadelphia. He changed his name when he was only 14, and as he ventured into a world of academics, this choice marked his new path in life.

Through hard work and a keen mind, he earned a scholarship to Temple University and later, another to Harvard, where he studied with some of the most brilliant minds of his time. These experiences shaped his thinking and his contributions to sociology.

Merton's work went beyond explaining why individuals turn to deviance. He was interested in the social processes and institutions that play a role in encouraging or discouraging such behavior. He wanted to understand how society's structure could exert pressure on individuals, pushing them towards acts that the very same society often condemns.

His insights laid the groundwork for what would become a cornerstone in the study of social deviance: the Strain Theory. He received many awards for his work, including the National Medal of Science in 1994.

Principles of Merton's Strain Theory

When you look around your community or school, you'll notice that everyone has aspirations – maybe it’s owning a home, graduating college, or landing a dream job. These are common goals that society encourages.

Now, according to Merton's Strain Theory of Deviance, society also dictates how you should achieve these goals through acceptable methods – like getting an education or working hard at your job. These are the cultural goals and institutionalized means that frame our lives.

But what happens when the means to these goals are unevenly distributed? Think of a classmate who has all the latest tech gadgets to help with school, while another may not even have a reliable internet connection. This is where strain creeps in.

The strain is the tension that arises when people recognize a gap between what society tells them they should have and what they're able to get through legitimate means.

This tension can lead to five different types of adaptation, as Merton outlined. Some conform to the expectations, continuing to chase their goals with the means they have. Others innovate, finding new, sometimes unapproved ways to reach the same goals.

A third group might give up on the goals altogether because they seem unattainable, which Merton calls ritualism. Then there are the rebels who reject both the established goals and the means, wanting to create a new system entirely. Lastly, some retreat, withdrawing from society's goals and means, like hermits or outcasts.

Merton's Strain Theory points out a significant flaw in the fabric of society. It's not only about individual choices but about the social structure that can corner people, leading them to choose paths that society labels as deviant.

It's a powerful framework for examining the disparities in opportunity within society. By applying Merton's principles, we begin to see not just behavior but the broader social patterns that can influence people's choices. This perspective invites you to consider not just what deviance is but why it exists and what social changes might be necessary to reduce it.

The Five Modes of Adaptation

Merton's Strain Theory is particularly insightful when it comes to the concept of adaptation. Adaptation is how people react to the strain between societal goals and the means available to achieve them.

Imagine you're in a game show but the challenges are unfair. How you decide to continue the game is your mode of adaptation.

Merton identified five of these modes, which help us understand the different paths people might take in response to societal pressures.

1) Conformity

First, there's conformity. Conformists play by the rules, even if they see others cutting corners. They believe in the goals society sets and the traditional ways of reaching them. This is like playing the game show honestly, even if it seems like you can't win.

2) Innovation

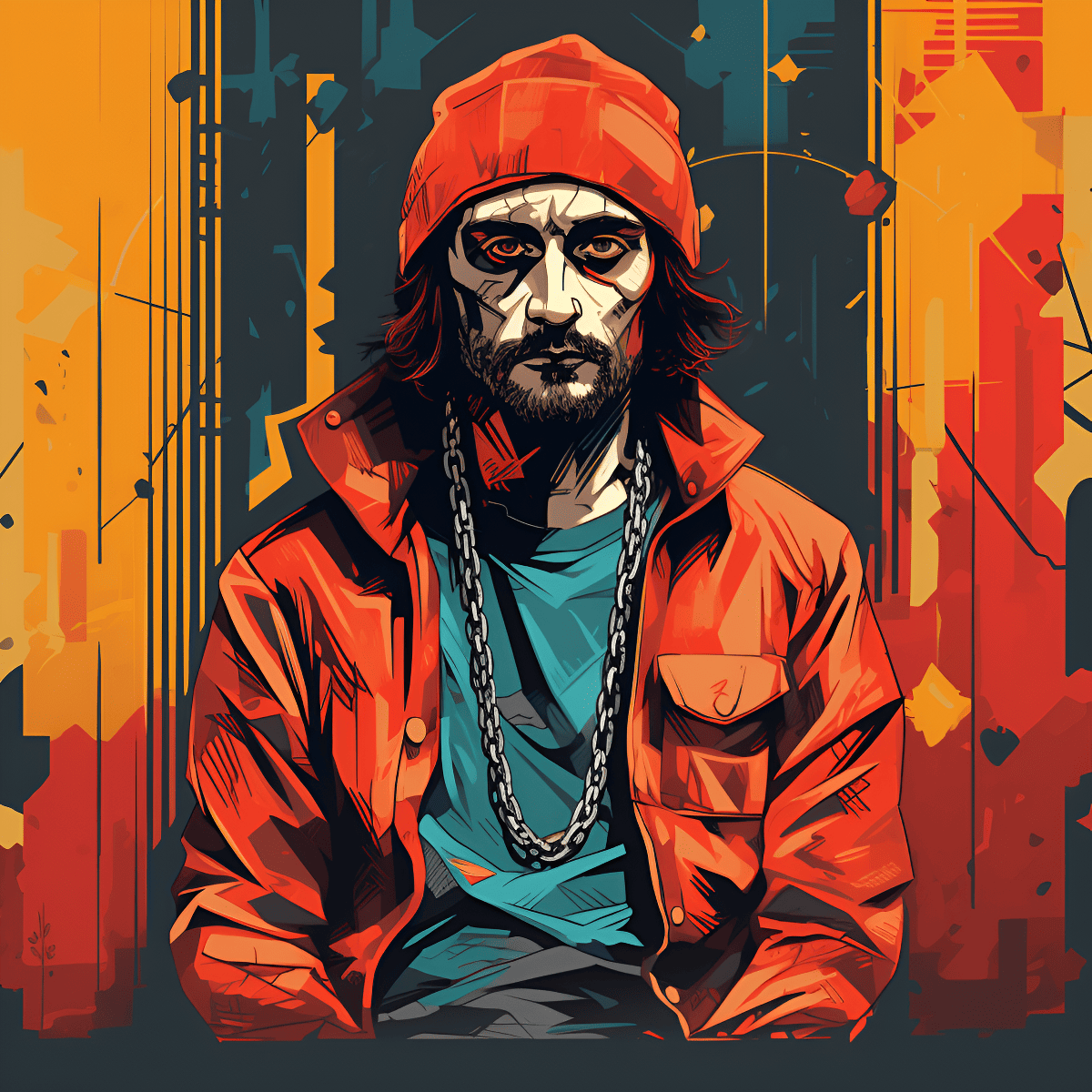

Next is innovation. Innovators still want to win, but they'll get creative with the rules. They desire the same goals but use unaccepted methods to achieve them. Think of a game show contestant who finds a loophole to advance to the next round.

3) Ritualism

Then we have ritualism. Ritualists might start to doubt the game itself, thinking the win isn't worth it, but they still go through the motions without hoping to actually achieve those goals. It's like playing the game show for the sake of participation, not to win the big prize.

4) Retreatism

Retreatism is the fourth mode. Retreatists reject the game's goals and rules entirely. They've given up on winning or even playing. In life, this could look like withdrawing from society's expectations altogether.

5) Rebellion

Finally, there's rebellion. Rebels want to change the game itself. They don't agree with the goals or the means, so they push for a new game with new rules. This mode can drive social change, as rebels often want to transform society itself.

Examples of Strain Theory

Strain Theory looks at both the cultural goals and an individual's ability to achieve success in those goals through legal and legitimate means. This is often impacted by their economic and social class.

Let's take a look at a few examples of institutions where Merton's theory gets acted out.

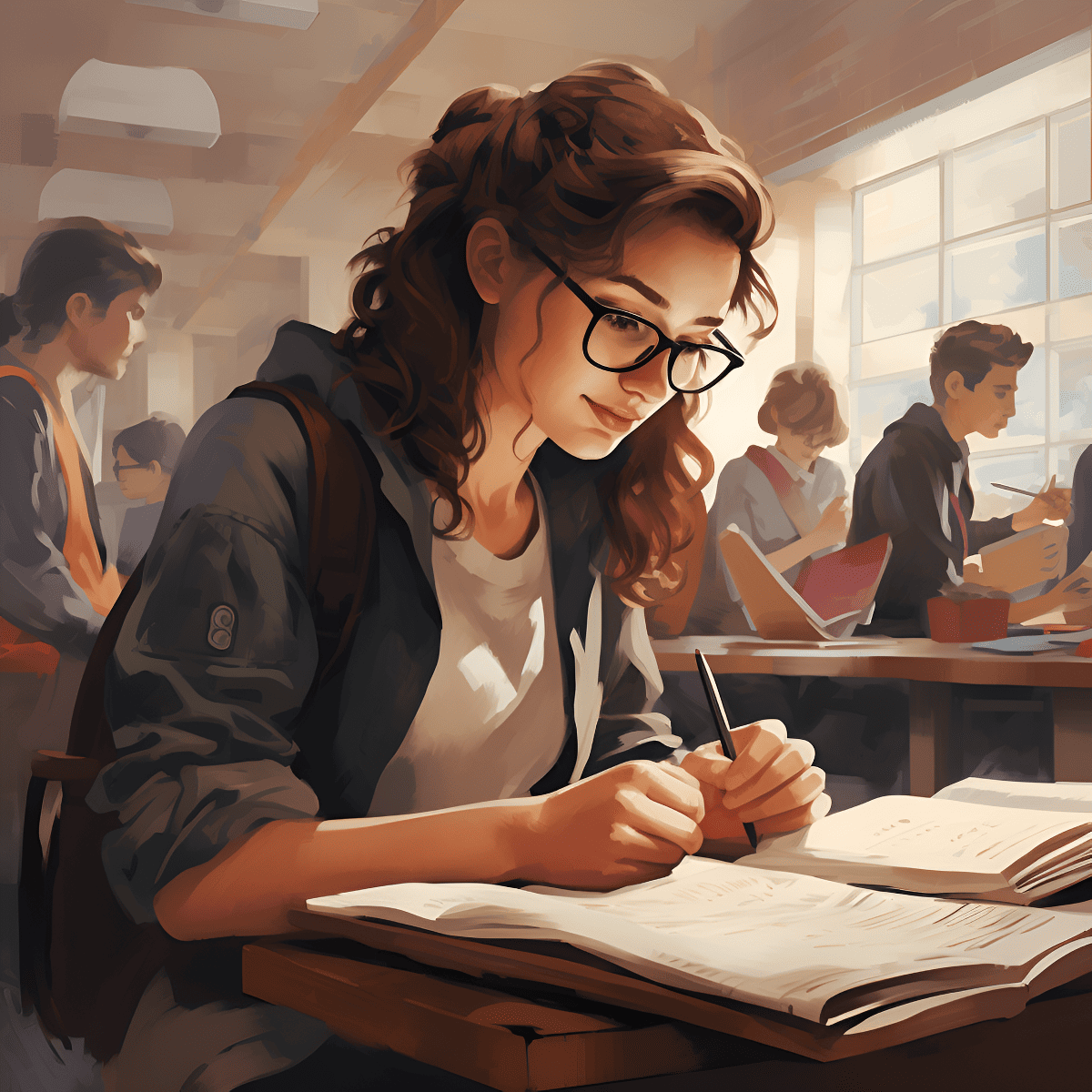

Schools

Consider the education system. Schools often promote the idea that anyone can succeed with hard work and talent. However, not every student has the same support or resources. This disparity creates strain.

Some students, following the conformist adaptation, may study tirelessly with the resources they do have, aiming for scholarships and opportunities. Others might resort to innovation, possibly cheating on exams to achieve the high grades that seem to be the ticket to success.

Jobs

In the workplace, the strain might come from the push to achieve professional success and financial stability.

Employees might adapt through ritualism by doing their job without any real hope for advancement, just going through the motions. On the other end, some might become retreatists, feeling so disconnected from the goals and means prescribed by society that they drop out of the workforce.

Economy

Then there's the broader societal picture, where wealth and power disparities are evident. Some groups might adopt the rebel adaptation, advocating for systemic change to create a more equitable society.

Strain Theory also helps to explain societal reactions to economic downturns. When the usual means to achieve financial stability are disrupted, increases in deviant behaviors such as theft or fraud might be understood as innovative responses to strain.

On the other hand, increased community engagement and support networks may emerge as a conformist response, adhering to societal values of cooperation and support.

Understanding these adaptations in the context of Strain Theory allows us to see beyond individual actions to the social pressures that shape them. It encourages empathy and could guide policies and interventions aimed at reducing strain and offering more equitable means for achieving success.

Whether it’s in schools, workplaces, or wider society, Merton's theory gives us a framework to identify and address the structural causes of deviant behavior.

Strain Theory and Crime

Let's connect Merton's Strain Theory to something you might hear about often: crime.

When society's pressure cooker gets too intense, and legitimate pathways to mental health and success are blocked, some individuals might turn to crime as a form of adaptation. It's not an excuse for criminal behavior, but an explanation from a sociological standpoint.

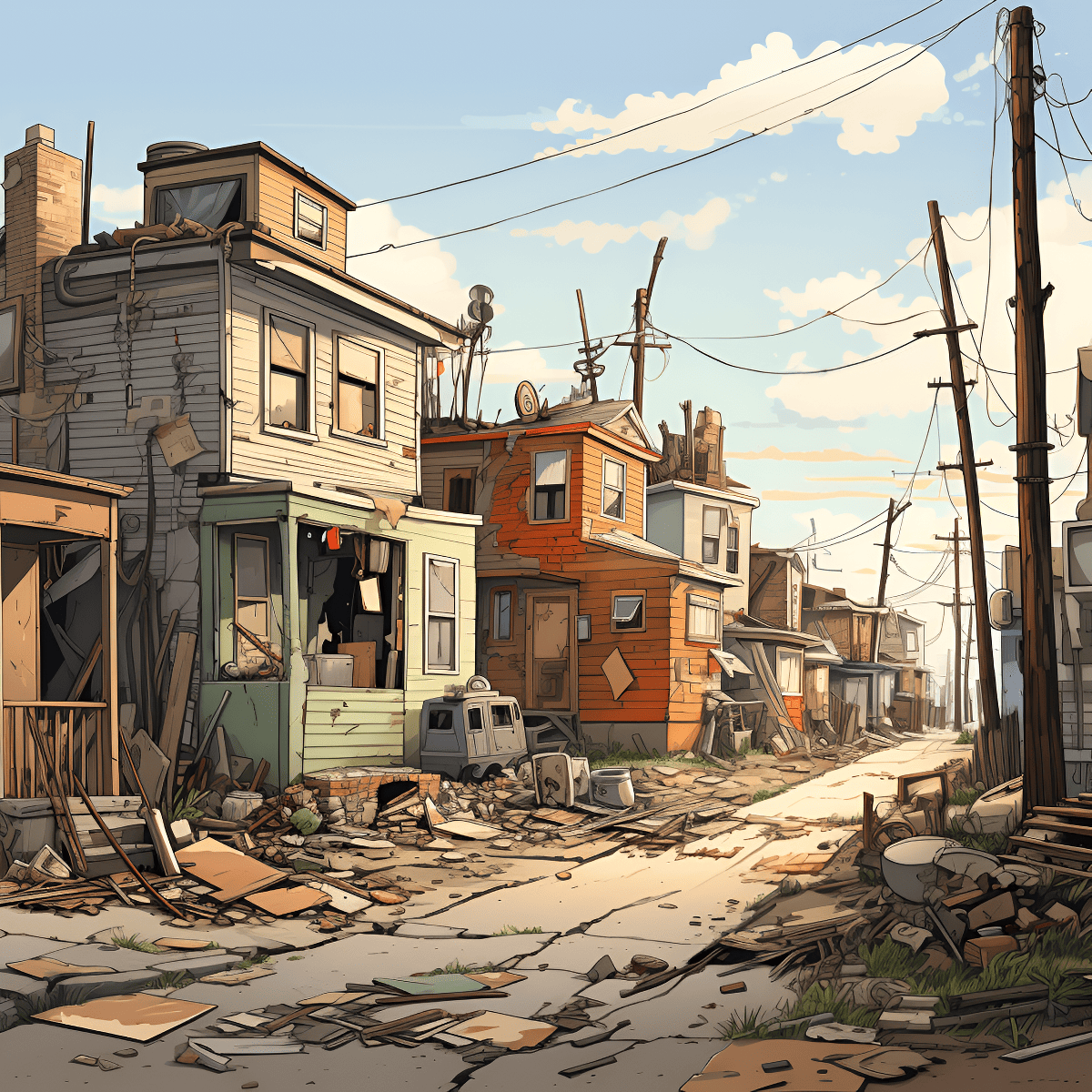

In neighborhoods where opportunities are scarce, the strain can be heavy. The cultural goal of financial success remains, but the means to achieve it legally are limited.

This is where innovation comes into play. For some, the innovation might take the form of engaging in illegal activities, such as selling drugs or theft, as an alternate route to achieve wealth.

Now, think about ritualism in the context of crime. You might see people who no longer aim for societal goals of success and wealth, but they still adhere to legal behavior, perhaps working low-paying jobs without hope for advancement. Their adherence to the rules is a way to cope with the strain without needing to commit crime.

Retreatism might manifest as substance abuse or vagrancy, where individuals have retreated from both the goals and the means of society. They're often viewed as having "dropped out" of the race altogether.

For rebels, their deviation might lead to criminal behavior, but with a different intent. They might engage in politically motivated crimes, aiming to disrupt the status quo and draw attention to their cause for societal change.

Understanding the relationship between strain and crime can lead to more effective strategies for crime prevention and rehabilitation.

Instead of solely increasing police presence or toughening penalties, addressing the root causes of strain—like inequality, lack of education, and unemployment—could mitigate the conditions that often lead to criminal adaptations.

In schools, this knowledge could prompt programs that provide more equitable opportunities and support for students. In the economy, it could influence policies that aim to provide more equal access to job opportunities and fair wages.

By using Merton's Strain Theory as a guide, society can work toward solutions that not only reduce crime but also address the underlying social inequalities that often lead to it.

Evidence for Strain Theory

To see Merton’s Strain Theory in action, let's look at real-world evidence and examples. These stories and studies show how the theory works outside of textbooks, in the lives of real people.

A powerful example comes from studies of crime rates during economic downturns. When jobs are lost and financial strain hits, there's often a spike in property crimes like theft.

People who are desperate to make ends meet may turn to these innovative ways to achieve their goals when the legitimate means—like employment—are blocked.

Research also points to the strain felt by groups who experience discrimination. When equal opportunities are denied because of race, gender, or ethnicity, the strain can lead to deviant adaptations.

In these cases, rebellion might manifest as protests or civil disobedience, aimed at changing the system that creates the strain.

Another example is in schools with high dropout rates. Often, these are institutions in underprivileged areas where students feel the strain of limited resources and support.

The choice to drop out can be seen as a form of retreatism, where the goal of educational achievement is abandoned because it seems unattainable.

But it's not all negative. There are positive examples, too, like communities that pull together to create their own opportunities when external ones are lacking.

This could be a neighborhood that starts a community garden to tackle food scarcity—an innovative and conformist response to strain that is both deviant (it bucks the status quo) and socially positive.

Criticisms of Merton’s Strain Theory

Every theory has its critics, and Merton's Strain Theory is no exception.

Some scholars argue that Strain Theory oversimplifies the causes of deviance. It suggests that societal pressures are the main reason people engage in deviant behavior, but we know individuals are complex.

People have personal and psychological factors that also play a role. It's like saying hunger is the only reason someone might eat an entire cake; it's a part of the picture, but there are other reasons, like stress or celebration.

Another point of critique is that Merton’s theory primarily focuses on lower-class deviance and overlooks white-collar crime, which can be significant. High-status individuals may commit crimes for reasons other than strain, such as greed or the thrill of risk-taking.

Additionally, the theory has been critiqued for its assumption that everyone agrees on what society’s goals are. In reality, different groups may have different values and aspirations, and what is considered a "deviant" behavior in one culture might be celebrated in another.

Lastly, Merton’s Strain Theory is sometimes seen as deterministic, implying that people in strained circumstances will inevitably turn to deviance. But we know this isn't always the case. Many people in tough situations do not resort to deviance; they might find strength in community, religion, or other social supports.

Understanding these criticisms is essential for applying Merton's Strain Theory responsibly. It's not a one-size-fits-all explanation and shouldn’t be used to stereotype or predict individual behavior. Instead, it can serve as a tool for understanding certain patterns of behavior within the broader context of social structures and pressures.

Contemporary Views and Adaptations

Merton's Strain Theory has been expanded and adapted by contemporary sociologists to fit our modern world.

General Strain Theory

One significant update to Strain Theory comes from Robert Agnew, who developed the General Strain Theory in the 1990s. You can think of this like a revised classic strain theory now.

Agnew broadened the idea of strain to include more than just the disconnect between goals and means. He included the experience of negative emotions like anger and frustration as a response to negative stimuli, such as abuse or failure.

Imagine you're not just stressed because you can't reach a goal, but also because you face constant criticism or unfair treatment. That's the kind of strain Agnew is talking about.

General Strain Theory also looks at how individual personality traits and support systems can influence how strain is experienced and how one might respond. So, not everyone under strain turns to deviance; some find positive ways to cope, thanks to their personality or a strong network of friends and family.

Technology

Another contemporary view considers the impact of societal change on strain. As technology, economies, and social norms shift, so do the types of strain people experience. Today, someone might feel strain from the pressure to be successful on social media, a type of strain Merton never could have predicted.

Globalization

Contemporary adaptations of Strain Theory are also applied to understand transnational issues, such as immigration and globalization. The strains experienced by immigrants, for instance, can include the challenges of assimilation and discrimination, which may influence the ways in which they adapt to their new environments.

How to Remember Merton's Strain Theory

Studying can sometimes feel like a memory marathon, but there are clever ways to keep Merton’s Strain Theory at the front of your mind, especially when exams loom.

One handy method is to create a mnemonic device. Take the first letter of each of the five modes of adaptation—Conformity, Innovation, Ritualism, Retreatism, Rebellion—and make a catchy phrase such as: Can I Remember Relevant Responses?

Draw diagrams, too. Imagine society's goals as a mountain everyone is trying to climb. Sketch paths representing the legitimate and illegitimate means used, and draw alternative routes for each adaptation.

Finally, apply the theory to familiar stories or movies. Characters often face strains and choose different paths, just like in Merton's theory.

For instance, in a superhero movie, the villain might turn to crime (innovation) due to being denied recognition (strain). Mapping these examples onto Strain Theory can cement your understanding and make study sessions a bit more fun.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1) What is Merton's Strain Theory of Deviance?

Merton's Strain Theory of Deviance suggests that society puts pressure on individuals to achieve socially accepted goals (like wealth or success), but not everyone has the same ability to achieve these through legitimate means. When there’s a disconnect between goals and socially approved means, it can lead to deviant behavior.

2) How does Strain Theory explain crime?

Strain Theory explains crime by saying that when people feel strain or pressure because they can't achieve cultural goals through legitimate ways, they may turn to crime to achieve those goals. This can involve theft to secure financial stability or fraud to achieve business success.

3) Can Strain Theory be applied to all societies?

Merton's Strain Theory is mostly applied to societies that have a strong emphasis on certain goals like wealth and material success, and where there is a defined structure of socially acceptable means to achieve these goals. It may not apply as well in societies with different values or where success is seen in more diverse ways.

4) How can we use Strain Theory to reduce crime?

By understanding the social pressures that lead to crime, communities and policymakers can work to provide equitable opportunities and support systems. This could involve creating more jobs, providing better education, or offering social programs that help reduce the strain people feel.

5) Does Strain Theory only apply to economic goals?

No, while Merton's theory often focuses on economic goals, it can apply to other culturally valued goals, such as educational achievements, social status, or even the “American Dream” of overall life success.

6) How can teachers use Strain Theory in the classroom?

Teachers can use Strain Theory by recognizing the different ways students might respond to the pressures of academic achievement. Understanding these can help teachers support students who may be at risk of engaging in deviant behavior due to strain.

7) Is Strain Theory relevant in today's society?

Yes, Strain Theory remains relevant as it can be applied to contemporary issues such as the pressures of social media, the stress of economic inequality, and the expectations placed on individuals in modern society.

8) How does Strain Theory relate to other sociological theories of deviance?

Strain Theory complements other theories by focusing on the social structures that influence individuals, whereas other theories might focus on individual psychology (like control theory) or the act of labeling someone as deviant (like labeling theory).

Conclusion

Remember, Merton's work is a lens through which we can view the pressures of societal norms and the lengths to which people will go to meet or reject those expectations.

From the bustling corridors of high schools to the fluctuating dynamics of the job market, Strain Theory offers explanations for the diverse responses to the shared challenges of living in a society with rigid success narratives.

Merton's Strain Theory of Deviance remains a significant contribution to the field of sociology, offering a timeless framework for analyzing the relationship between society and the individual.