B. F. Skinner was an American psychologist, researcher, philosopher, inventor, and author. He is best known for his scientific approach to studying human behavior and his contributions to behaviorism. Skinner believed all human behavior is acquired via conditioning and that free will is an illusion. The American Psychological Association ranks Skinner as the most eminent psychologist of the 20th century.

B. F. Skinner's Childhood

Burrhus Frederic Skinner was born on March 20, 1904, in Susquehanna, Pennsylvania. Susquehanna was a small coal and railroad town located in the hills. Skinner’s parents were Grace and William Skinner. His brother Edward was two and a half years younger than him.

Skinner’s father worked as a lawyer. William Skinner bought many books and built a large library in his home. Skinner’s mother, Grace, was a homemaker. Skinner grew up in a religious family and was raised as a Presbyterian. He described his home environment as “warm and stable.”

Much of Skinner’s childhood was spent outdoors roaming the hills of Susquehanna. He was an active, energetic young boy who loved to build things. He once built a cart, but accidentally put in the steering backwards. He also tried and failed to build a perpetual motion machine. However, he was successful in building a host of other devices such as rafts, sleds, slides, roller-skate scooters, merry-go-rounds, slingshots, bows and arrows, water pistols, blow guns, and a cabin in the woods.

Skinner attended the same high school as his mother and father. He played the saxophone and piano at home and played in a jazz band at school. Perhaps his most influential teacher was Miss Mary Graves, who taught him English and art. Her guidance likely played a role in Skinner enjoying his time in high school and majoring in English Literature in college. He later dedicated his book The Technology of Teaching to her.

As was the family custom, Skinner attended Presbyterian Sunday school each week. These religious classes were also led by Miss Graves, who was a devout Christian. While Skinner’s grandmother had a fire-and-brimstone approach to religion, Miss Graves had a more liberal view of the bible. At first, Skinner enjoyed the contrasting views of his grandmother and Miss Graves, but as he got older, he lost interest in religion. One day he approached Miss Graves and told her he no longer believed in God.

Although the Skinner household was generally happy, Skinner and his parents experienced a devastating loss during his adolescence. Skinner’s younger brother Edward had a cerebral hemorrhage and died at the age of sixteen. Edward was closer to his parents than Skinner was, and Edward’s death caused his parents to focus more on Skinner. Even though Skinner loved his parents, he was not always comfortable with the extra attention.

Educational Background

After graduating from high school, Skinner went to Hamilton College in New York. His goal was to major in English Literature. However, Skinner did not fit in well with college life at Hamilton. He thought it was absurd to take courses such as anatomy, embryology, mathematics, and biology because they did not relate to his major. He did not enjoy college football and parties. And as an atheist, he disliked the mandatory daily chapel attendance.

Skinner graduated from Hamilton College in 1926 with a bachelor's degree in English Literature. Shortly before leaving school, he made the decision to return home and become a writer. After failing to write a captivating novel, he chose to focus on short stories. However, Skinner only managed to write a few short newspaper articles over the course of the next year. He believed he had “nothing important to say” because he lacked the perspective and life experiences necessary to become a good writer.

While working as a bookstore clerk in New York, Skinner considered writing about science instead of fiction and happened to read Bertrand Russel’s book Philosophy. This book highlighted the research of John B. Watson and introduced Skinner to behaviorism. He then read an article written by H.G. Wells about the work of Ivan Pavlov. Skinner was intrigued. He submitted an application to study psychology at Harvard University and was accepted in 1928.

Skinner received his master’s degree in psychology in 1930. One year later, he earned his PhD in psychology. Skinner was awarded several fellowships that allowed him to continue his research at Harvard until 1936.

Ivan Pavlov was one of Skinner’s biggest influences. Skinner adopted Pavlov’s belief that if you can control the environment, you can see the order in behavior. The majority of Skinner’s research involved animal studies with rats or pigeons. He invented a number of devices for his experiments, the most popular of which was the “Skinner box.” Over time, Skinner developed his own version of behaviorism called radical behaviorism.

In 1936, Skinner accepted a teaching position at the University of Minnesota at Minneapolis. During this time, much of the research he had started at Harvard was put on hold. When World War II erupted, Skinner was very eager to contribute to the war effort and attempted to train pigeons to help guide missiles to enemy ships. Eventually the project was discontinued with the rise of radar.

Skinner moved to Indiana University in 1945 and served as the chair of the psychology department. However, Skinner rejoined the Harvard faculty as a tenured professor in 1948. He spent the rest of his professional career at Harvard.

Skinner's Accomplishments in Radical Behaviorism

Skinner was a staunch supporter of the behaviorist movement in psychology. However, he diverged from the form of behaviorism advanced by the founder of the movement, John B. Watson. Watson believed that psychology should concern itself only with overt, observable behaviors. He argued that private events (such as thoughts, feelings and perceptions) are not fitting subject matters since they cannot be directly observed or studied in an objective manner.

While Skinner agreed that observable behaviors should be the primary focus of psychology, he did not reject the role of internal events. He believed private events could also be included in a scientific study of behavior. However, such events should not be regarded as explanations for behavior, but rather, as behaviors that need explanation themselves. He pointed to the environment as the ultimate determinant of behavior, both internal and external. Skinner’s approach to the study of behavior became known as radical behaviorism.

Another distinction between traditional and radical behaviorism relates to the importance placed on stimulus-response (S-R) relationships. Classical behaviorists like Watson and Pavlov felt that all behaviors occur in response to stimuli that preceded them. Skinner disagreed. While the stimulus-response theory can explain reflexive actions, he argued that it does not adequately account for more complex forms of behavior. He proposed that such behaviors are determined by the consequences they produce. This belief forms the basis of his theory of operant conditioning.

What Is Operant Conditioning?

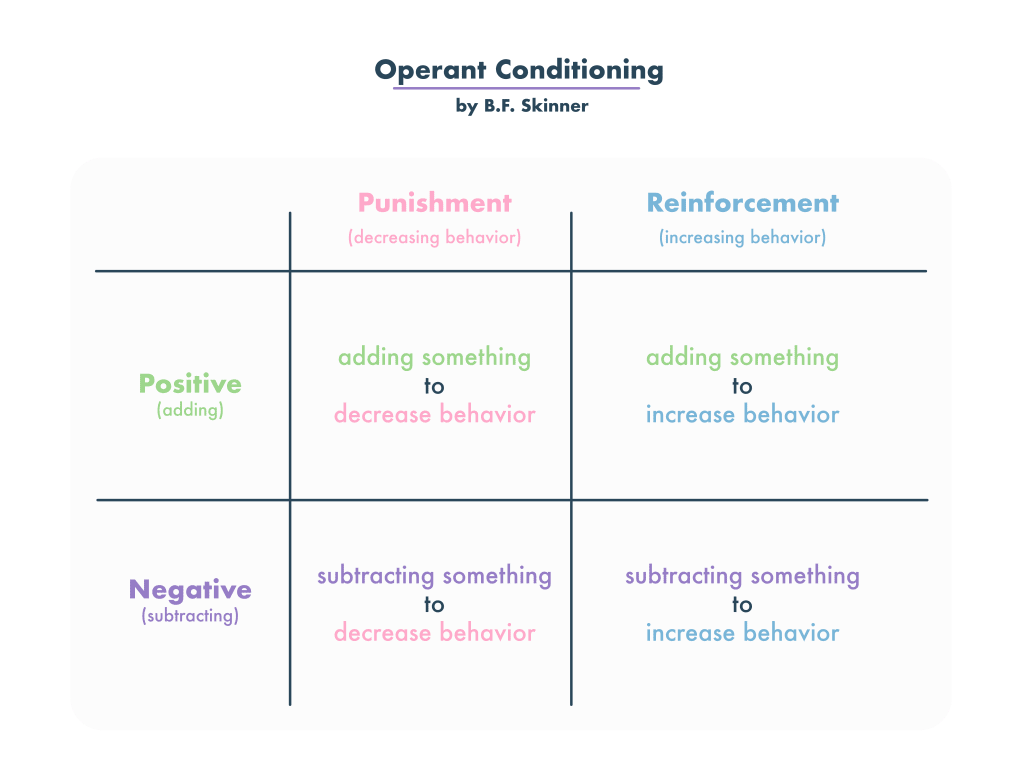

Operant conditioning is a form of learning in which the consequences of a behavior influence the likelihood of that behavior being repeated in the future. Skinner outlined two types of consequences - reinforcement and punishment. Reinforcement refers to any consequence that increases the likelihood of a behavior recurring; punishment is any consequence that decreases it.

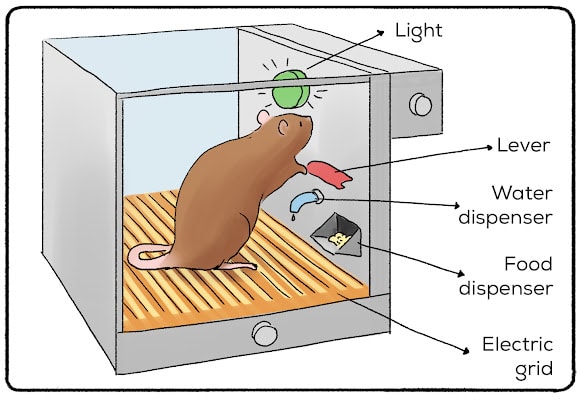

To test his theory of operant conditioning, Skinner conducted numerous animal experiments. Many of these involved the use of an enclosed chamber known as the ‘Skinner box.’ In one version of the experiment, a hungry lab rat is placed inside a Skinner box equipped with a lever. When pressed, the lever causes food pellets to be delivered to the rat. At first, the rat’s behavior is quite random as it explores its new environment. If by chance the rat presses the lever and receives a food pellet, its behavior soon changes. The food acts as a reinforcer, causing the rat to deliberately press the lever more frequently.

Skinner called this form of learning operant conditioning because the organism actively operates on the environment, producing a consequence. This stands in stark contrast to stimulus-response learning, in which a behavior is passively elicited by the stimulus that preceded it. In operant conditioning, the organism actively chooses to behave in a particular way, with that behavior being influenced by the consequences that follow.

Skinner further broke down each type of consequence into positive and negative forms. Here, ‘positive’ simply refers to the addition of a stimulus following the behavior, while ‘negative’ refers to the removal of a stimulus. Reinforcement (whether positive or negative) always strengthens behavior; punishment (whether positive or negative) always weakens it.

- Positive reinforcement - a rewarding stimulus is presented following the behavior (eg., you play peek-a-boo with a baby and the baby smiles at you; a child gets a lollipop for tidying up his room)

- Negative reinforcement - an aversive stimulus is removed following the behavior (eg., your flatmate stops banging on your door when you turn your radio down; the annoying beeping sound stops when you buckle your seatbelt)

- Positive punishment - an aversive stimulus is added as a consequence of the behavior (eg., you receive a ticket for driving over the speed limit; you get an ‘F’ on your test for copying from your friend)

- Negative punishment - a rewarding stimulus is removed as a consequence of the behavior (eg., Nora stays out past curfew so her dad takes her cell phone away; you burp loudly at dinner and your date suddenly stops smiling)

Principles of Operant Conditioning

Operant conditioning of complex behaviors often involves a process known as shaping. This involves reinforcing successive behaviors that gradually come closer to the behavior you ultimately wish to reinforce. For example, if you wish to train your dog to roll over on command, you could wait until he performs this behavior spontaneously and then reward him for it. You would then have to wait for the dog to repeat this behavior several times since a single instance of reinforcement would not be enough for him to learn the behavior. No doubt, that would require a great deal of patience.

A much faster approach would be to reinforce the dog for successive behaviors leading up to the desired response. For example, you might start by giving the dog a treat when he sits. Once the dog learns that behavior, you might withhold reinforcement until he lies down. Later, you might present a reward only when he lies down and rolls onto his back, and finally, only when he lies down and rolls over completely.

Once a behavior has been conditioned (i.e., learned) in the presence of a given stimulus, there is a tendency for the organism to produce that behavior in the presence of similar stimuli. This is known as stimulus generalization. For example, if a rat learns to press a lever for food when it sees a green light come on, he might also press the lever when a red light is switched on.

The opposite of stimulus generalization is stimulus discrimination. This is the tendency for a conditioned response to occur in the presence of certain stimuli but not in the presence of others. The organism learns to distinguish between stimuli that signal a reward and those that do not. If a rat receives a shock for pressing a lever when a red light is on, but receives food for performing the same behavior when a green light is on, it will quickly learn to press the lever only in the presence of a green light.

Skinner also found that if a conditioned response is no longer reinforced, it will gradually diminish. For example, if a baby no longer smiles when you make a silly face, you will eventually stop making that face. This process is known as extinction.

The pace at which a conditioned behavior becomes extinct depends in large part on the schedule of reinforcement maintaining that behavior. A schedule of reinforcement is simply a pattern by which responses are reinforced. The two broad types of schedules spoken of by Skinner are continuous and partial.

In continuous reinforcement, every instance of a desired response is reinforced. For example, a child might get a bonus on his allowance every time he aces a math test. In partial reinforcement, some, but not all, instances of the desired behavior are reinforced. The occasional payout received from playing a slot machine is an example of partial reinforcement. Behaviors that are partially reinforced tend to be more resistant to extinction than those that are continuously reinforced.

What Was B.F. Skinner's Position on Free Will?

By showing how behaviors could be learned through outside consequences and rewards, his theories lean to the "determinism" side of the argument. (Users discuss this further in this Reddit post about Skinner's positions.) It is important to note that while his theories are applied today, not everyone who cites or studies him sees the free will vs. determinism argument in black and white measures.

How is Skinner’s Theory Used Today?

Many real-world applications of operant conditioning theory exist. These include:

Behavior modification programs - these programs are designed to increase desirable behaviors and minimize or eliminate undesirable ones. Many of the techniques used in behavior modification are based on the principles of operant conditioning. In one of these techniques, known as a token economy, participants are awarded tokens for appropriate behavior. The tokens (eg., points, coins, or gold stars) can then be exchanged for items or privileges that are reinforcing for the individual. Token economies can be implemented at home, or in institutions such as schools, prisons and psychiatric hospitals.

Animal training - animal trainers typically employ the technique of shaping in order to teach complex tricks. By successively rewarding responses that inch closer and closer to the target behavior, trainers have managed to teach animals complex maneuvers and stunts that might otherwise have been impossible.

Biofeedback training - Biofeedback has been used to treat conditions such as anxiety and chronic pain. Individuals are taught techniques such as deep breathing and muscle relaxation, which help to alter involuntary bodily responses such as heart rate, blood pressure and muscle tension. As they engage in these behaviors, recording devices measure bodily changes and transmit the information to them. Positive changes (eg. a lowered blood pressure reading) reinforce the behaviors that preceded them.

Superstitions - many superstitions result from accidental reinforcement. Take for example a gambler who happens to blow on his dice just before a big win. Even though his success has absolutely nothing to do with the act of blowing on the dice, he will likely keep engaging in that behavior because it has been reinforced.

Addiction - Drug and alcohol addiction can be explained by the reinforcing effects of these substances. Addictive substances influence the brain’s reward system, resulting in feelings of pleasure (positive reinforcement) and relief from pain, anxiety and discomfort (negative reinforcement). The individual is therefore motivated to engage in repeated drug use. Operant conditioning principles also account for behavioral addictions, such as gambling.

Criticisms of Skinner’s Theory

Skinner conducted numerous studies to support his view of human nature. However, most of these studies were conducted in laboratories using small animals such as rats and pigeons. Critics argue that generalizations about human behavior cannot be made on the basis of these studies since humans are much more complex. Humanistic psychologists, in particular, claim that Skinner’s approach is overly simplistic since it does not take into account uniquely human characteristics such as free will.

Skinner has also been criticized for ignoring the role of cognitive and emotional factors in learning. Some have argued that Skinner’s approach promotes a mechanical view of human nature in which humans are seen as slaves to the consequences of their actions. Contrary to what Skinner believed, studies have shown that reinforcement and punishment are not necessary for learning to take place. Behaviors can also be learned through observation and insight.

B. F. Skinner's Books, Awards, and Accomplishments

B. F. Skinner was a prolific writer who published 180 scholarly papers and 21 books. His literary works include:

- The Behavior of Organisms: An Experimental Analysis (1938)

- Walden Two (1948)

- Science and Human Behavior (1953)

- Schedules of Reinforcement (1957)

- Verbal Behavior (1957)

- Cumulative Record (1959)

- The Analysis of Behavior: A Program for Self-Instruction (1961)

- The Technology of Teaching (1968)

- Contingencies of Reinforcement: A Theoretical Analysis (1969)

- Beyond Freedom and Dignity (1971)

- About Behaviorism (1974)

- Particulars of My Life (1976)

- Reflections on Behaviorism and Society (1978)

- The Shaping of a Behaviorist: Part Two of an Autobiography (1979)

- Notebooks (1980)

- Skinner for the Classroom (1982)

- Enjoy Old Age: A Program of Self Management (1983)

- A Matter of Consequences: Part Three of an Autobiography (1983)

- Upon Further Reflection (1987)

- Recent Issues in the Analysis of Behavior (1989)

Skinner received honorary degrees from several universities, including:

- Alfred University

- Ball State University

- Dickinson College

- Hamilton College

- Harvard University

- Hobart and William Smith Colleges

- Johns Hopkins University

- Keio University

- Long Island University C. W. Post Campus

- McGill University

- North Carolina State University

- Ohio Wesleyan University

- Ripon College

- Rockford College

- Tufts University

- University of Chicago

- University of Exeter

- University of Missouri

- University of North Texas

- Western Michigan University

- University of Maryland, Baltimore County.

Skinner also received a multitude of prestigious awards throughout his career. Some of these awards are listed below:

- 1930−1931 Thayer Fellowship

- 1931−1932 Walker Fellowship

- 1931−1933 National Research Council Fellowship

- 1933−1936 Junior Fellowship, Harvard Society of Fellows

- 1942 Guggenheim Fellowship (postponed until 1944–1945)

- 1942 Howard Crosby Warren Medal, Society of Experimental Psychologists

- 1949−1950 President of the Midwestern Psychological Association

- 1954−1955 President of the Eastern Psychological Association

- 1958 Distinguished Scientific Contribution Award, American Psychological Association

- 1964−1974 Career Award, National Institute of Mental Health

- 1966 Edward Lee Thorndike Award, American Psychological Association

- 1966−1967 President of the Pavlovian Society of North America

- 1968 National Medal of Science, National Science Foundation

- 1969 Overseas Fellow in Churchill College, Cambridge

- 1971 Gold Medal Award, American Psychological Foundation

- 1971 Joseph P. Kennedy, Jr., Foundation for Mental Retardation International award

- 1972 Humanist of the Year, American Humanist Association

- 1972 Creative Leadership in Education Award, New York University

- 1972 Career Contribution Award, Massachusetts Psychological Association

- 1978 Distinguished Contributions to Educational Research Award and Development, American Educational Research Association

- 1978 National Association for Retarded Citizens Award

- 1985 Award for Excellence in Psychiatry, Albert Einstein School of Medicine

- 1985 President's Award, New York Academy of Science

- 1990 William James Fellow Award, American Psychological Society

- 1990 Lifetime Achievement Award, American Psychology Association

- 1991 Outstanding Member and Distinguished Professional Achievement Award, Society for Performance Improvement

- 1997 Scholar Hall of Fame Award, Academy of Resource and Development

- 2011 Committee for Skeptical Inquiry Pantheon of Skeptics—Inducted

Personal Life

Skinner married Yvonne Blue in 1936. They had two daughters named Julie and Deborah. Skinner died from leukemia on August 18, 1990. Ten days before he died, he accepted the lifetime achievement award from the American Psychological Association and gave a talk based on the article he was currently working on. He completed his final article the same day he passed away.

References

American Psychological Association. (2002). Eminent psychologists of the 2th century. Monitor on Psychology, 33 (7) 29. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/monitor/julaug02/eminent

Aubrey, K., & Riley, A. (2019). Understanding and using educational theories (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

B. F. Skinner Foundation. (n.d.). Biographical information. Retrieved from https://www.bfskinner.org/archives/biographical-information/

B. F. Skinner Foundation. (n.d.). Books by B. F. Skinner. Retrieved from https://www.bfskinner.org/publications/books/

Jarvis, M., & Okami, P. (2020). Principles of psychology: Contemporary perspectives. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Kelland, M. D. (2019). B. F. Skinner and the behavioral analysis of personality development. Retrieved from

Milan, M. A. (1990). Applied behavior analysis. In A. S. Bellak, M. Hersen & A. E. Kazdin (Eds.), International handbook of behavior modification and therapy (2nd ed.) (pp. 67-84). New York: Plenum Press.

Powell, R. A., Symbaluk, D. G., & Honey, P. L. (2009). Introduction to learning and behavior (3rd ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Schultz, D. P., & Schultz, S. E. (2005). Theories of personality (8th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth.