Reconstructive memory has influenced social psychology and it may influence the way that you write the story of your life.

What Is Reconstructive Memory?

Reconstructive memory is the process in which we recall our memory of an event or a story. Psychologist Federic Bartlett discovered was that as an event happens, we don’t perceive as much as we think. To recall the event, we have to pull from “schema” to fill in the blanks.

Schema includes our knowledge of similar events or cultural influences. These schemas often color our memory, sometimes inaccurately.

Examples of Reconstructive Memory

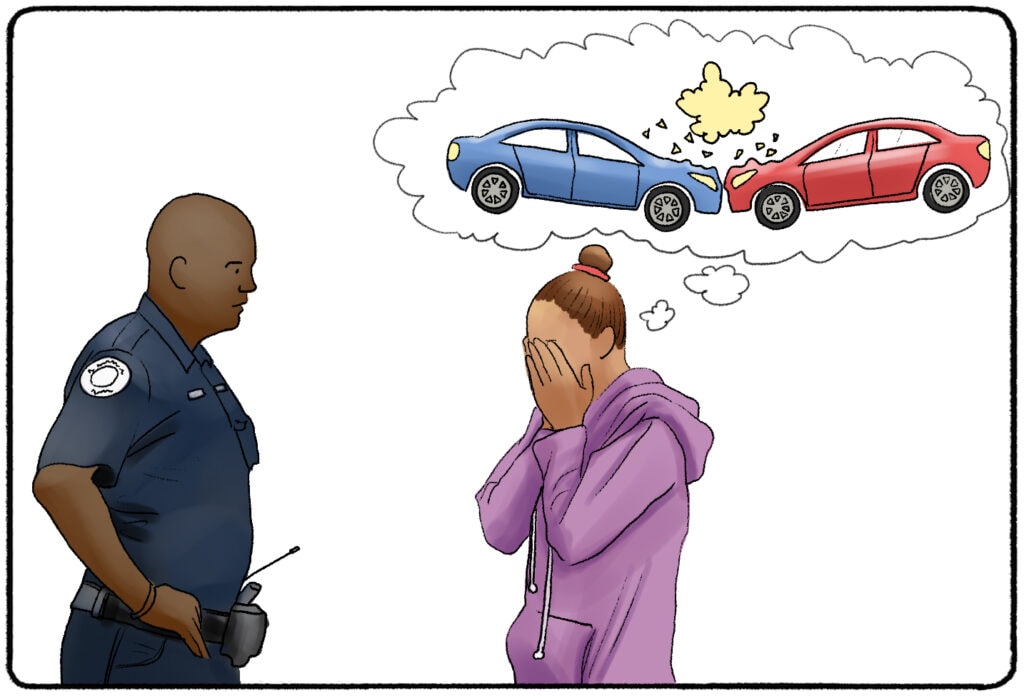

Let’s say you are asked by police officers to recall everything you did, saw, and experienced on a certain day last week. You have to pull from your episodic memories or the memories of everyday events that play out like an episode of TV. You, the center of the memory, can tell the story of the day from your perspective. If you’re confident in your memory recall, you might tell the officers that you are sure to have seen a certain person on the street or that you didn’t hear anything.

But is that memory as accurate as you think?

Who Came Up with Reconstructive Memory? Federic Bartlett’s Experiments

How did Federic Bartlett develop his ideas of reconstructive memory and schemas? He conducted experiments. His most famous experiments surrounding reconstructive memory include a folk tale called The War of the Ghosts.

In the first experiment, Bartlett read the story to participants, sometimes twice. He asked participants to recall the story after 15 minutes, and then later after different intervals of time. Bartlett would record what the participants recalled and how long their reports of the story were.

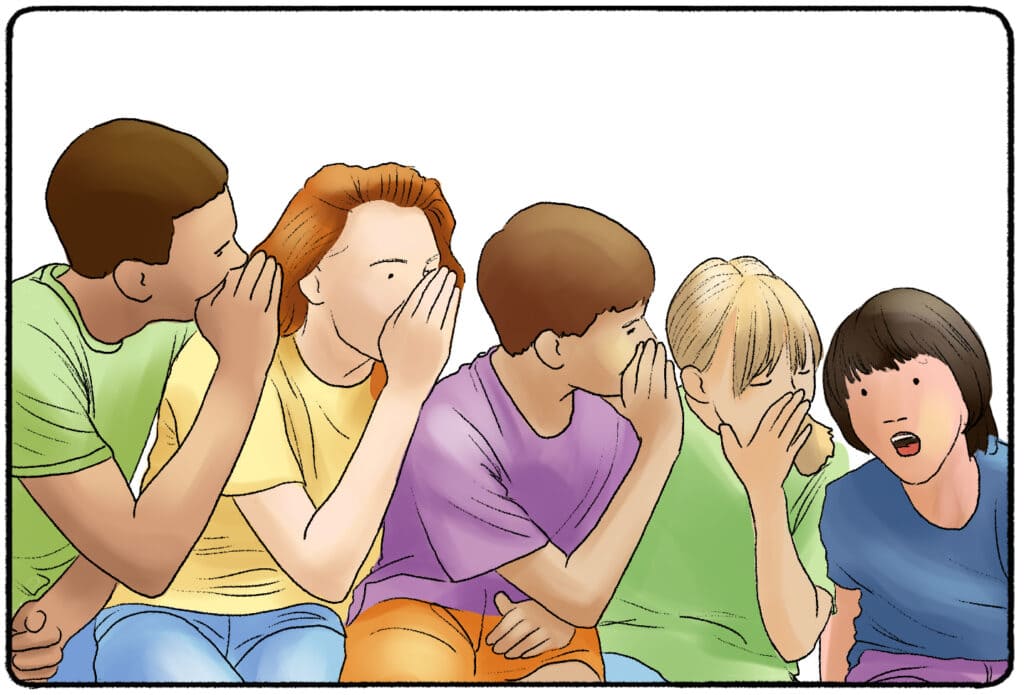

In another experiment, Bartlett set up a task similar to the game of telephone. Have you ever played a game of “Telephone?” All of the participants sit in a line. At the start of the line, one person whispers a word or a phrase to the person next to them. They have to repeat the word or phrase to the person next to them, and so on. If you’ve played this game, you know that things can get twisted very quickly. The person at the end of the line may hear a completely different phrase than the phrase at the beginning of the line.

What if you did this with a longer story?

Certainly, things would get twisted, right?

That’s what Federic Bartlett believed in the early 20th century. Bartlett set up a game of telephone and would then read the participant’s retelling to another participant, and the process would repeat a number of times. In his book Remembering: A Study in Experimental and Social Psychology, he does tests out these beliefs. He uses a “game” similar to that of Telephone to support the idea of reconstructive memory.

This theory is also known as the reconstructive theory of forgetting.

More Examples of Reconstructive Memory

Reddit user Triunka asked the Ask Reddit subreddit: "What is the most profound reconstructed memory you haven’t realised was fake until much later?" The answers are pretty fascinating!

Results of the Experiment

In both experiments, the story got twisted. The more time that had passed, the less that would be remembered by participants. Participants in the first experiment produced shorter and shorter reports as they were repeatedly asked to recall the story. The story was also altered more when communicated through the “game of telephone.” If someone in the chain’s memory was especially faulty, it would significantly alter the information that the rest of the chain received.

But Bartlett was interested in more than just how much information the participants were able to recall. He was also interested in what the participants recalled. The patterns he found led to the development of the idea of schema.

Remember, the participants in the story were British. Bartlett read a foreign folk tale to them. This tale included details about ghosts - after all, it is called The War of The Ghosts. But Bartlett noticed that any mention of ghosts tended to disappear after multiple recalls of the story. The more that time passed, the less likely a participant was to mention ghosts.

Bartlett noticed that other details were likely to be omitted from the recall, including hunting for seals, details surrounding a canoe trip, and the names of the towns in the story. Basically, any details that didn’t “fit” into British culture at the time were more likely to be omitted. Some specific words were likely to be replaced or altered so that they fit into British culture.

Schema and Social Psychology

What does this say about our ability to recall memories?

Bartlett believed that it showed how the memory recall process worked. At the time of the event, we don’t perceive as much as we might think. In order to fill in the blanks of what we don’t remember, we pull from schemas.

Schemas are patterns that we use to categorize information. A schema may refer to a stereotype, the idea of someone’s role in society, or a framework. We build and reinforce schemata early on in our development, as described by social psychologist Jean Piaget.

For example, if you listened to a lot of fairy tales as a child, you are likely to develop a “schema” for fairy tales. This schema starts with “once upon a time” and includes all of the elements of a traditional fairy tale.

Bartlett noticed that many of the participants, familiar with the idea of fairy tales, would reconstruct the memory of the story into the fairy tale format. Some participants even added a “moral” to the end of a story, as if it were a fairy tale.

The idea of schema is still used in psychology and cognitive therapy today. And experiments on memory still show that our memories aren’t as accurate as we may think, even if they are significant events in our lives. (You can learn more about flashbulb memories here!)

The less we know about an event, the less likely we are to recall it later. Our minds find it “easier” to explain events and memories using concepts and ideas that we are already familiar with. How might this alter your memories of travel, events, or other information that you learn?