From not remembering where we left our keys to forgetting the name of a person we’ve just met, memory failures are a daily occurrence. But why do they happen? Not everyone has the same answer. Psychologists and neuroscientists have developed five theories of forgetting that attempt to explain why our memories get foggy or slip away from us entirely.

What Are the Five Theories of Forgetting?

Throughout the years, psychologists have created five theories of forgetting in an attempt to explain how and why memories slip from our minds. Not all of these theories are still accepted. Some were even created in response to theories that came before them! Some can easily be true alongside other theories of forgetting. All these theories will make you think about the mysterious nature of forgetting information.

The five theories of forgetting include:

- Displacement theory

- Trace decay theory

- Interference theory

- Retrieval failure theory

- Consolidation theory

Theory #1: Displacement Theory of Forgetting

The displacement theory describes how forgetting works in short-term memory. Short-term memory has a limited capacity and can only hold a small amount of information—up to about seven items—at one time. Once the memory is full, new information will replace the old one.

There seems to be no one figurehead of this theory, but many psychologists have contributed to experiments and studies that support it. Free recall method studies often support the idea of the displacement theory of forgetting. This theory is pretty solid and has stood the test of time.

Displacement theory plays neatly into the Multi-Store Model of Memory. This model shows that while some information reaches long-term memory, other pieces of information in short-term memory storage are simply forgotten. What pieces of information are displaced? Keep on reading.

Serial Position Effect

In studies based on the free-recall method, participants are asked to listen to a list of words and then try to remember them. The free recall method, unlike the serial recall method, allows participants to remember words in no particular order. Through these studies, psychologists have discovered that the first and the last items on a list are the easiest ones to remember. They named this phenomenon the Serial Position Effect. Two other effects, the primacy and recency effects, explain why the first and last items are so crucial in memory.

The primacy effect suggests that recalling the first item on the list is simple. At the time they are presented, these initial words don’t yet compete with the subsequent ones for a place in the short-term memory.

The recency effect explains why the participants remember items at the end of the list. These words have not yet been suppressed from short-term memory. The words in the middle of the list, pushed out from the short-term memory by the last words, are much less likely to be recalled.

Examples of the Displacement Theory of Forgetting

Suppose you have just learned a seven-digit phone number when you are given another number to memorize. Your short-term memory doesn’t have the capacity to store both information. In order to recall the new phone number, you’ll have to forget the first one. This isn't always a conscious process, but it can be. The moment you begin to focus on the new set of numbers, the first one seems to "go away" or get confused with the new numbers you are learning.

Another example of the displacement theory of forgetting involves grocery lists. As you walk out the door to the grocery store, your partner tells you that you need to buy "milk, eggs, cheese, flour, and sugar." You try to memorize the whole list, but a lot of it goes away while you are driving to the store. When you arrive, all you can remember is "milk" and "sugar."

Theory #2: Trace Decay Theory of Forgetting

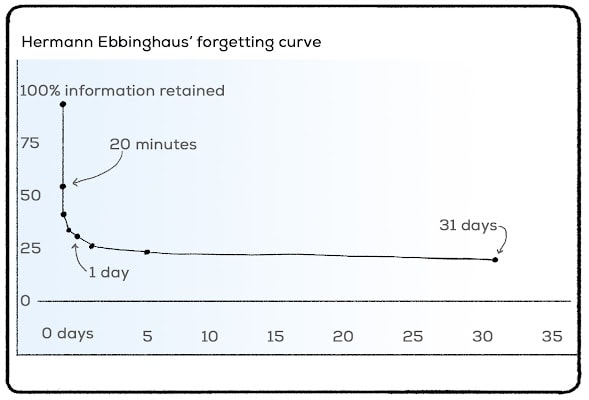

The trace decay theory was formed by American psychologist Edward Thorndike in 1914, based on the early memory work by Hermann Ebbinghaus. The theory states that if we don’t access memories, they will fade over time.

When we learn something new, the brain undergoes neurochemical changes called memory traces. Memory retrieval requires us to revisit those traces that the brain formed when encoding the memory. The trace decay theory implies that the length of time between the memory and recalling determines whether we will retain or forget a piece of information. The shorter the time interval, the more we will remember, and vice versa.

Serial Probe Task

In 1965, Waugh and Norman put both displacement theory and trace decay theories to the test. They put participants through a "serial probe task." Each participant listened to a long list of letters. Later, the researchers would yell out one of the letters from the list, and the participants would have to name the letter listed after. What they found showed that displacement theory could explain some instances of forgetting, but not all of them.

The interesting part of the results was that when the list was read at a faster pace, participants completed the task more successfully.

Criticisms and Need for Other Theories of Forgetting

The trace decay theory, however, doesn’t explain why many people can clearly remember past events, even if they haven’t given them much thought before. Neither does it take into account the role of all the events that have taken place between the learning and the recall of the memory. Just like the serial probe task suggests that displacement theory is not "enough," decay theory fails to cover all instances of forgetting and remembering.

The interference theory concentrates precisely on the aspects of forgetting that decay theory fails to address.

Theory #3: Interference Theory of Forgetting

The interference theory was the dominant theory of forgetting throughout the 20th century. It asserts that the ability to remember can be disrupted both by our previous learning and by new information. In essence, we forget because memories interfere with and disrupt one another. For example, by the end of the week, we won’t remember what we ate for breakfast on Monday because we had many other similar meals since then.

The first study on interference was conducted by German psychologist John A. Bergstrom in 1892. He asked participants to sort two decks of word cards into two piles. When the location of one of the piles changed, the first set of sorting rules interfered with learning the new ones, and sorting became slower.

Proactive interference (Example)

Proactive interferences take place when old memories prevent making new ones. This often occurs when memories are created in a similar context or include near-identical items. Remembering a new code for the combination lock might be more difficult than we expect. Our memories of the old code interfere with the new details and make them harder to retain.

Retroactive interference (Example)

Retroactive interferences occur when old memories are altered by new ones. Just like with proactive interference, they often happen with two similar sets of memories. Let’s say you used to study Spanish and are now learning French. When you try to speak Spanish, the newly acquired French words may interfere with your previous knowledge.

Theory #4: Retrieval Failure Theory of Forgetting

The retrieval failure theory was developed by the Canadian psychologist and cognitive neuroscientist Endel Tulving in 1974. According to this theory, forgetting often involves a failure in memory retrieval. Although the information stored in the long-term memory is not lost, we are unable to retrieve it at a particular moment. A classic example is the tip of the tongue effect when we are unable to remember a familiar name or word.

There are two main reasons for failure in memory retrieval. Encoding failure prevents us from remembering information because it never made it into long-term memory in the first place. Or the information may be stored in long-term memory, but we can’t access it because we lack retrieval cues.

Retrieval cues

A retrieval cue is a trigger that helps us remember something.

When we create a new memory, we also retain elements of the situation in which the event occurred. These elements will later serve as retrieval cues. Information is more likely to be retrieved from long-term memory with the help of relevant retrieval cues. Conversely, retrieval failure or cue-dependent forgetting may occur when we can’t access memory cues.

Semantic cues

Semantic cues are associations with other memories. For example, we might have forgotten everything about a trip we took years ago until we remember visiting a friend in that place. This cue will allow recollecting further details about the trip.

State-dependent cues

State-dependent cues are related to our psychological state at the time of the experience, like being very anxious or extremely happy. Finding ourselves in a similar state of mind may help us retrieve some old memories.

Context-dependent cues

Context-dependent cues are environmental factors such as sounds, sight, and smell. For instance, witnesses are often taken back to the crime scene that contains environmental cues from when the memory was formed. These cues can help recollect the details of the crime.

Theory #5: Consolidation Theory of Forgetting

While the above theories of forgetting concentrate principally on psychological evidence, the consolidation theory is based on the physiological aspects of forgetting. Memory consolidation is the critical process of stabilizing a memory and making it less susceptible to disruptions. Once it is consolidated, memory is moved from short term to a more permanent long-term storage, becoming much more resistant to forgetting.

The term consolidation was coined by Georg Elias Muller and Alfons Pilzecker in 1900. The two German psychologists were also the first to explain the theory of retroactive interference, newly learned material interfering with the retrieval of the old one, in terms of consolidation.

Other Theories of Forgetting

These five theories are most frequently mentioned when discussing forgetting, memory, and recall. Psychologists have devised other theories that may be worth looking into. No one theory of forgetting covers all incidences of memory loss and recall, so these theories are valid, too!

Motivated Theory of Forgetting

Friedrich Nietzsche was one of the first psychologists to suggest that people intentionally forgot their memories. Typically, these memories are traumatic or shameful. This theory really took off when Freud expanded upon this theory. Freud spoke more about the idea that people unintentionally forgot their memories. This process is called repression and is considered a defense mechanism. Freud, however, believed he could recover repressed memories. Today, psychologists mostly discredit this idea, as the mind can "change" memories with leading questions and other methods. Still, this motivated theory of forgetting is an important idea in the history of psychology.

Gestalt Theory of Forgetting

The Gestalt Theory of Forgetting attempts to explain how memories can be forgotten through a process called distortion. This does not have to be an intentional process, either. If memory is hazy or missing pieces of information, the brain will fill in those pieces. The memory may feel accurate but is actually distorted.

Which of these theories of forgetting is correct? Maybe all of them, in their own ways!